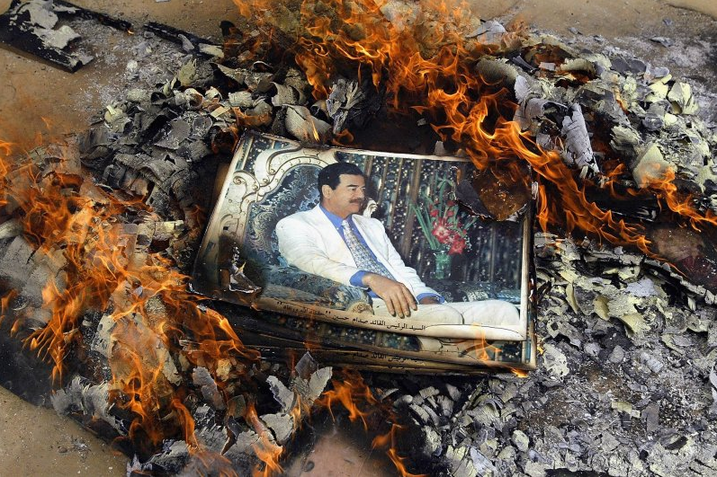

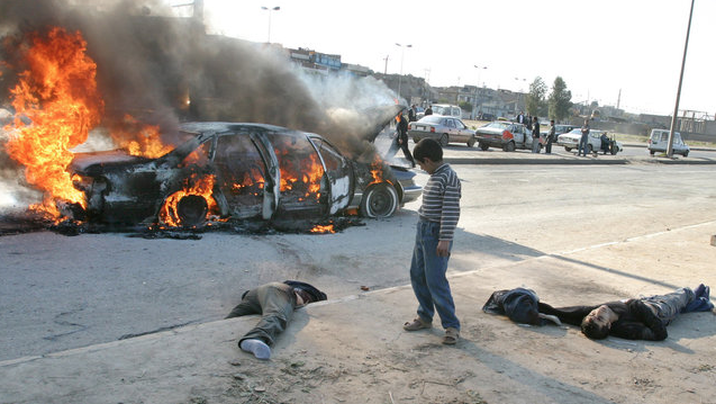

This started as an impression. I noticed, as you may have done, that there seemed to be fewer of those mayhem stories that were a daily staple a year ago: fewer ghastly suicide bombings, fewer vanloads of corpses discovered at dawn, fewer kidnappings and beheadings. Horrors of the kind described so vividly by Dahr Jamail on the pages that follow now come our way only occasionally.

A trawl of our national press over last weekend appeared to confirm this. In the four days from Friday to Monday the downmarket papers barely mentioned Iraq, and where they did it was usually in the context of “our boys” going out there or coming home. At the upper end of the market, with one exception to which I will return, any attention given to Iraq was focused on the danger of a Turkish-Kurdish conflict in the north. All was quiet, it seemed, on the Baghdad front.

Could this be good news? Perhaps General Petraeus’s surge is making headway, bringing some order and humanity to this blood-soaked place. That is certain what the general himself would have you believe. He recently told reporters that the threat from Al Qaeda in Iraq was “significantly reduced. The group had fewer strongholds, fewer hiding places and less support among the Sunnis, he said, though he warned it was still capable of landing a “big punch”.

Moving swiftly on

Visualise the morning news conference at a daily paper, where, once again, the foreign editor informs his colleagues that there has been a heavy death toll inside Iraq. Somebody will pipe-up: “any Brits?” The answer will be no. Someone else will ask: “Is this a new peak?” The answer will again be no, since deaths are actually down from last year. And the discussion will swiftly move on to Hillary Clinton or the EU treaty or whatever is next on the foreign list.

The consciences foreign editor, of course, will seek fresh ways to bring terrible facts to the reader, and here we meet two more problems. First, the familiar option of reporting events through the prism of politics, of supplying meaning through what people are saying, is not available because there are no real politics in Iraq. Second it is extremely dangerous to gather firsthand information of the kind that gives depth and human context to the bloodshed -- the Committee to Protect Journalists counts 29 journalists killed in Iraq this year alone.

Keeping such risks to a minimum is not cowardly. I applaud Dahr Jamail’s courage, but it goes far beyond what the newspaper reader has a right to demand of flesh-and-blood reporters. That is why embedded reporting has proved attractive, offering as it does the chance to see at least something of what is going on, but with reduced risk.

Yet embedding with British forces is becoming rarer, perhaps because their remit is now so limited . The one paper to devote space to Iraq over the weekend was the Sunday Telegraph, which had a despatch from an embedded reporter who painted a miserable picture of an isolated force with no information sources and no function, camped outside a city in the grip of militias. On that basis, you have to wonder how much more embedding there will be: the reporters only learn about discontent in the army, and the Ministry of Defence can’t want that.

Perhaps I’m wrong, and this lull in the reporting of Iraq’s miseries will be temporary. Then again, perhaps this dreadful conflict we helped to create is becoming just one more of those unending tales of woe (Somalia, Lebanon, Burma …) that we read about only occasionally and shake our heads at in despair. I suspect that Petraeus, Bush and brown would all settle for that.

Brian Cathcart is a professor of journalism at Kingston University.

Source : Brian Cathcart, New Statesman, November 5 2007

RSS Feed

RSS Feed