Within the special position they occupy, journalists are bound by professional norms which in the last decade of coverage on Iraq have been tailored in ways that reflects the geopolitical preferences of regional and international powers.

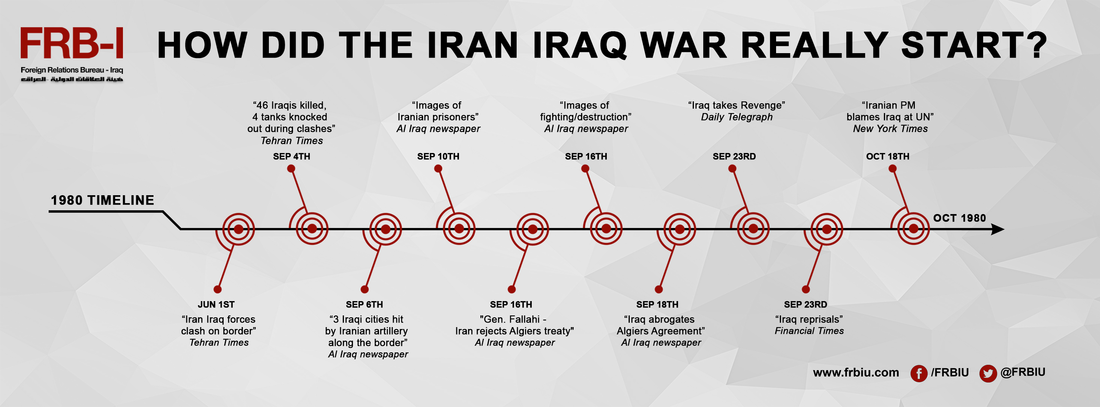

On September 22 1980, following a military operation led by Iraqi President Saddam Hussein’s army, 10 airfields across Iran were bombed by Iraqi jets. A quick google search tells us this was how the eight-year war began.

Trawling through archives, the reality one begins to uncover is far from this simple.

Between March 1979 and September 1980 Iran said it had suffered 807 attacks by Iraq, whilst Iraq conceded that it suffered 544 separate Iranian attacks. The tit-for-tat nature of these military operations, counters the narrative of Iraq as being the only aggressor, thirsty for war. One begins to recognise a pattern of attacks that force analysts to reassess popular accounts of the war.

Coverage of artillery duels and skirmishes that culminated in Iraq’s multi-pronged aerial attack on September 22 do exist, but have been noticeably absent from conventional historiography yet easily accessible from archives.

State-run Iranian newspapers Kayvan and Tehran Times provide accounts of fighting as early as April that year. Arabic language Iraqi press contends that Khomeini’s entry into politics revived decade-old territorial disputes and differences that, as is documented, began to flare between September 1979 and September 1980.

Baghdad had long rejected the September 22 postulation, citing September 4 as the date when Iran began shelling Iraqi villages on the border.

This and other important developments — Khomeini’s repeated calls for the overthrow of the Baath government -- have been scrubbed from the collective memory. Embracing this version of history allows one to bypass media bias and its role in setting the parameters of public opinion in later years.

“A cruel” and “despotic government” Iranian prime minister Mohammad Ali Rajai told the UN, Oct. 17 1980, had instigated the war.

“The entire world must know that Saddam’s army has acted without mercy, without pity, like Hitler’s armies” Rajai went on.

Numerous communiques Iraq sent to the newly established Islamic Iranian Republic received not a single mention by papers to coveraged Rajai’s address. Nor were they interested in calls from Iraqi foreign minister Sadoun Hammadi, who in a letter to United Nations Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim, put pressure on Iran to relinquish control of Iraqi territory agreed to be returned under the Algiers Accord.

The hyperbolism Rajai displays that has been recycled within journalistic and policy circles has gone on to shape ‘universal facts’ surrounding the conflict.

Disputes have been commonplace for the past 5 centuries where efforts to delimit borders have repeatedly been made and unmade, offering insights from the past.

In 1639 warring Ottoman and Safavid Persia created a border zone, in which individual tribes and villages were able to choose where their loyalties lay, to end, albeit temporary, territorial disputes.

With backing from the British Empire and Russia the subsequent treaty of Erzerum was signed in 1847 for the development of steam ship navigation through the Shatt al-Arab to satisfy imperial aspirations of expansion in the region.

Between the signing of Erzerum and the Algiers Accord more than a century and a quarter later, issues surrounding territorial sovereignty were tamed, but remained unresolved due to the difficulty of establishing a true boundary in Shatt al Arab’s changeable environment.

Most recently, in 1975, the Algiers Accord was signed which again attempted to resolve disputes over the Shatt al Arab boundary and towns along the Iran-Iraq border.

Relations took a turn for the worse following the Iranian revolution in 1979. Promises made by former Iranian Shah Pahlavi were either ignored or retracted — leaving the Algiers Agreement in limbo.

The fate of territories (Zain Al-Qaws and Saif Sa’ad) that the algiers accord recognised as Iraqi were left unresolved. Contrary to the agreement reached five years prior, Iran maintained its grip over them.

On September, 14 Iranian General Fallahi as quoted by state-run Fars News Agency said “Iran does not recognise the Algiers Accord” promising that not an inch of land would be relinquished to Iraq.

Yet despite the fact that Fallahi’s address was put out in both Iranian and Iraqi media, this fact has been ignored by any subsequent reports of the war, despite its significance and consequences.

Just two days later Saddam Hussein publicly abrogated the Agreement, in an interview which was aired internationally, in response to what he saw as provocations from the Iranian leadership.

This marked the escalation of clashes that would eventually spawn an all out war.

Reporting the day after Iraq’s attack on Iranian airfields (September 23), the Financial Times and Daily Telegraph referred to the operation as ‘reprisals’ and ‘revenge’ respectively. This suggests that the narrative of Iraq as the instigator of war had not yet been decided upon.

Relying on these sources would not have brought anyone seeking answers to this puzzling dilemma any closer to the truth. Without the context to hostilities and disputes between both nations it is impossible to fully understand why the war began.

The blame game has long served the agenda of foreign actors that have gone to sustain Saddam’s legacy to justify 4 decades of military presence, and thus the destruction and destabilisation of Iraq.

The story told by western media outlets has not been delivered objectively, despite having at their disposal a trail of evidence to help plug the gaps this research identifies.

Almost every summation written after 1990 negates the role that was played by Iran, portraying Iraq as the sole aggressor.

The past as we know is not unbroken and linear. Why then is one version elevated above others. Narratives are more than descriptive accounts of the truth, they operate at different levels in search of recruits from populations worldwide. Their unquestioned approval helps powers to advance policy objectives and to perpetuate their interpretation of history — as the case of Iraq demonstrates time and again.

In this post-factual news age, secondary sources must be read with caution, for scholarship that is moulded to project only one version of history sets a dangerous precedent for how we receive news.

Created with flickr slideshow.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed