Competitiveness is eroded as the real exchange rate appreciates, growth is jobless, governments adopt pro-cyclical fiscal policies, commodity dependency intensifies, and vulnerability to external shocks increases. There might be few deadlier curses than the combination of a corrupt government and a sick private sector. Unfortunately, as a recent report shows, Iraq is afflicted with exactly such a curse.

BROAD AGREEMENT ON PROBLEMS, AND NO CONSENSUS ON SOLUTIONS

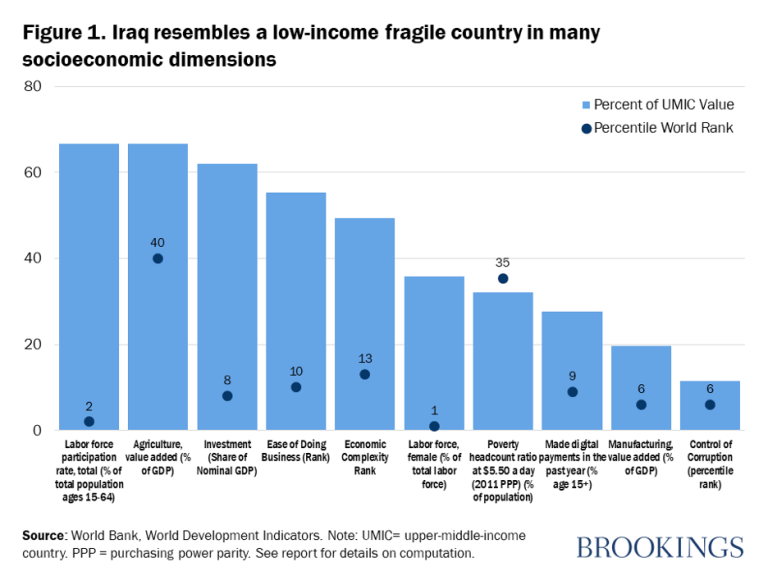

While oil wealth allowed Iraq to obtain upper-middle-income status, in many ways its institutions and socioeconomic outcomes resemble those of a low-income, fragile country. Growth is driven by oil production—and related investment—but not productivity.

The education system, once ranked near the top of the Arab world, now sits near the bottom. Iraq has one of the lowest female labor force participation rates in the world, a youth unemployment rate of 36 percent, deteriorating infrastructure and business conditions, and one of the highest poverty rates among upper-middle-income economies (Figure 1). Recent conflicts have also had huge economic costs: per capita GDP in 2018 was estimated to be about 20 percent lower than it would have been without the ISIS conflict.

There is a broad consensus that sustained growth, employment creation and better living standards for Iraqis require peace and stability, reduced oil dependency, and state dominance in favor of more market-oriented private sector participation, greater regional integration, and better public management of oil revenues. While these goals remain valid from a technical perspective, successive attempts to get to them by government and donors have proved largely elusive. We think that, in large part, this is because reform programs in Iraq have been designed outside a robust political framework.

CONTESTATIONS GONE BAD

Understanding fragility, violence, and limited development requires a careful analysis of the country’s political system, the nature of the social contract, and the social divisions in society. This can best be done using an analytical framework that looks at three levels of “contestation”: between political elites (“elite bargaining”), between the state and society (“social contract bargaining”), and between social groups (“social cohesion”). Applying such a framework in fragile, conflict, and violence affected countries helps to understand why reforms have gone wrong.

In Iraq, these three contestations have turned violent in recent history. Conflict has erupted over competition for power and resources, and Iraq’s elites have instrumentalized ethno-sectarian divisions in their pursuit of power. High levels of external interference reinforce these fault lines and turn Iraq into an arena for wider geopolitical contestation. Moreover, high levels of oil dependency have reinforced contestation at all levels, fueling elite competition and undermining the state’s accountability to citizens. Oil wealth has reduced incentives to mobilize other forms of government revenues, notably from taxation. This, in turn, has reduced the need for state-society bargaining and accountability, which are at the heart of successful state-building processes.

State-society contestation has emerged as a new fault line. The social contract between Iraq’s ruling elite and the people has failed to meet social demands, fueling growing discontent over poor services delivery, state corruption, and the lack of economic opportunities, as recent protests illustrate. Increasing political fragmentation has exacerbated the power struggle widening the divide between the ruling elite, which has sought to preserve the status quo, and its constituencies. Sixty-four percent of Iraqis say that the country is divided as opposed to unified.

The country’s political equilibrium will become even more fragile in the coming years given demographic dynamics—Iraq has one of the youngest populations in the world—and regional disparities in terms of both poverty and service delivery. Cohesion and social trust are particularly low in ISIS-liberated areas, while poverty rates are the highest in the South despite generating most of the oil wealth.

A BETTER MODEL

What are the shifts in thinking that this framework helps to identify? We can think of three: a refocused politics that includes every social group, a restored social contract that creates confidence, and a revised economic model that diversifies Iraq’s national asset portfolio.

- Refocus politics on development. Although institutional reform is a slow-moving and gradual process, it requires reform coalitions among both ruling elites and citizens in all social groups. Progress in Iraq will remain elusive unless elite incentives shift, and the country assumes a shared political vision that recognizes the need for a system that delivers development to all Iraqis.

- Restore the social contract. Building confidence between citizens and the government requires addressing grievances, delivering essential services, and nourishing hope. This includes strengthening institutions to respond to public concerns about corruption, strengthening citizen engagement in the delivery of key services and infrastructure, establishing a fiscal contract with citizens, and finding ways to create an investment climate that leads to job creation for Iraqi youth.

- Revisit the economic model. Focus on diversifying Iraq’s asset portfolio first and foremost by investing in people, improving the infrastructure, and strengthening the institutions for delivering social services, managing macroeconomic volatility, and regulating private enterprise.

Source (Click Here)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed