It is also in ill health.

So when images appeared on social media this June showing oil spills on the Shatt al-Arab in Basra, Iraqis immediately responded, voicing concern about a public health crisis.

Or rather, yet another public health crisis. For decades, the Shatt al-Arab has suffered from serious pollution. By 2018, fresh water was so scarce that the people of Basra faced an environmental catastrophe. Over 110,000 people became ill from polluted water sources, prompting mass demonstrations across the region.

Recent incidents do not bode well for the future; water supplies continue to be polluted by oil spills and sewage. In recent years, Basra’s residents have become increasingly active online, documenting incidents using their cellphones and sharing on social media or with journalists who reported on it. Alongside more traditional media sources, this civic activism has become invaluable in visualising, thereby documenting, the toxic legacy of structural neglect to public services and water infrastructure.

Back to the future

This environmental crisis has been in the making for decades, compounded by past conflicts and problems with pollution.

Famously, Iraq is blessed with the world’s fifth-largest oil reserves. However, that may been more of a curse for the country’s waterways. A 1985 research paper estimated that 200,000 tonnes of oil residue from were discharged into the Persian Gulf every year. As one research paper noted, “sewage discharge and urban run-off may be considered as the most significant sources of oil entering the Shatt al-Arab.”

Those words were written when war raged with neighbouring Iran. The 1980-1988 conflict marked the start of a series of calamities for the Shatt al-Arab.

Firstly, Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein drained the nearby marshes as punishment to local tribes whom he accused of aiding the enemy. This sensitive ecological habitat has yet to fully recover.

As war encroached deeper into Iraq, ships were sunk beneath the river’s surface. Shelling destroyed thousands of the date palms which were once the hallmark of Basra’s riverbanks and are an important cash crop for local people. According to a May 2020 research paper about the period, ‘soil fertility was depleted, irrigation infrastructure was neglected or destroyed, and cropland suffered from salinisation’.

Iraq’s 1991 invasion of Kuwait and subsequent international response also resulted in targeting some key infrastructure in and around Basra, including power stations necessary for sewage and water filtration.

Then came the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, which led to the near-complete collapse of the Iraqi governance, followed by a bloody insurgency in 2006. In the aftermath, there was little interest or investment in timely recovery programmes for damaged habitats, contributing to worsening conditions for environmental regulation and its enforcement.

Unable to compete with cheap foreign produce, local farmers suffered. In many cases, their date palms never recovered.

The oil industry was luckier. Thanks to foreign investment, it was even able to boost its production after the war. Although some foreign oil companies included environmental concerns in their oil exploitation, the environment remained under threat. Corruption among government officials reportedly worsened the lack of proper investment in Basra’s wider public sector and environmental infrastructure, including water and sanitation services, where communities often see little from the billions of dollars of oil revenues.

But they do receive trickle-down pollution from upstream.

Many of Iraq’s largest industrial facilities are located along the Tigris and Euphrates, before they combine to form the Shatt al Arab river. They include power stations, water treatment plants, and sewage stations, paper mills, international airports such as that in Basra, and many other oil-industry related facilities. This runoff has been found to contribute to pollution in the Shatt al-Arab.

Another study published in Nature Research in 2020 on pollution in the river found elevated levels of heavy metal contamination such as nickel, chromium, manganese, molybdenum, copper, lead and zinc with sources coming from fertilisers and sewage sludge, metal welding workshops, and the oil industry. Locals continue to protest against the oil industry, including its facilities used to inject water into oil wells.

The latter is also facing more scrutiny from Iraqi researchers, who noted in 2019 that despite the economic development it brought, the oil and gas industry contributed to air, land and water pollution. “Moreover, it has caused major social damage due to the diseases, occupational accidents, job injuries and depletion of non-renewable resources and energy for present and future generations”, continued the researchers. This July, the impact of air pollution on local communities was covered the New York Times, alongside other international media.

These are just some of the reasons why people in Basra took to the streets in mass protest in 2018. Remarkably, at that time, these problems had already been known to the government for over a decade. Reports from 2005 and 2009 by the Iraqi Ministry of the Environment acknowledged discharged wastewater from Basra city into the river, as well as ‘industrial, service, and agricultural water discharges’ from power stations, factories, and hospitals. A Ministry of Planning report from 2010 includes similar admissions, as did several others reviewed by Bellingcat.

A cocktail of hazardous pollutants has flowed into the Shatt al-Arab, making locals residents’ fight for environmental and social justice as urgent as it is grueling. But like observers of this crisis from afar, they now have something which previous generations do not — access to open source materials.

OSINT as a tool for environmental justice?

Social media platforms have long since become Iraqis’ primary source of receiving and sharing news, reflecting a wider mistrust towards news media since 2003. Reports indicate that a large number of Iraqi media outlets are owned by or affiliated to certain political parties, favouring certain sides in domestic political conflicts or other disputes where the interests of relevant actors are at stake. Thus, these partisan media outlets generally have not paid much attention to ecological issues such as water pollution or the impact of climate change and conflict on the environment.

To fill this gap, Iraqis have launched several Facebook pages which are used to document different environmental incidents, raising awareness and promoting local cleaning or greening campaigns. Their concern and their resourcefulness in documenting this environmental damage can easily be seen by searching Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube for Arabic phrases such as ‘ShattalArab’ [شط العرب], ‘pollution’ [تلوث], ‘shipwrecks’ [حطام سفن، سكراب سفن، غوارق], ‘sewage’ [مجاري، مياه مجاري، مياه اسنة] and ‘oil’ [نفط].

Importantly, the aforementioned 2009 Ministry of the Environment report is not the only indication that Iraqi authorities have known of these environmental problems for many years. In fact, several freely available documents from government ministries and international organisations alike suggest the same, further giving credence to protesters’ accusations of inaction.

Oil spills, from far above

Some of Iraq’s vast oil wealth makes it above ground in the form of spills that pollute the country’s largest rivers.

The 2009 report from the Ministry of Environment report outlines how oil impacts biodiversity through polluting surface water and beaches, in turn affecting aquatic life, birds and animals, while also damaging agricultural lands and orchards. There are also consequences for human health, too: the oil clogs filters at water purification stations, and through soil pollution it can enter the food chain. The image below shows examples of oil spills and pollution on the Shatt al-Arab.

A further oil spill was observed in the same location in March 2017, featuring in a TV report on NRT Arabic. Here oil waste or other pollutants came from Shatt al-Turk canal south of the facility.

Bellingcat was able to geolocate both the 2016 and 2017 videos to the vicinity of the Najibyah powerplant. Both TV items were made by Ahmad Abdul Samad, an Iraqi journalist who regularly reported on pollution until he was murdered with his cameraman in Basra in January 2020. Ahmad Abdul Samad had actively used social media to report on the Basra water crisis of 2018. In several posts, the journalist can be seen condemning the poor measures taken against pollution and the neglect shown towards Basra residents’ demands for clean and accessible water.

More footage of possible oil pollution was broadcast on August 29, 2018 by the Al Rafidain TV network. Bellingcat examined Sentinel-2 imagery from that date to establish whether oil spills were visible on the river, but couldn’t find any imagery of oil on the water. This suggests either that Al Rafidain’s footage actually showed the aforementioned spill from June-July, or that the discolouration was due to something else — potentially another source of pollution or a natural cause.

The sources of these reported spills seem to originate near the various power plants and factories along the river upstream in the city or above the city, such as the aforementioned Najibyah and Al Hartha power plants or the Ben Omar oil facility and its adjacent paper mills.

But the Shatt al-Arab is not only affected by local sources of pollution — after all, most of Iraq’s watershed drains into this estuary.

For example, on January 31, 2019, footage appeared on Twitter showing huge floodwaters coming from neighbouring Iran, bringing with them pollution and crude oil. While the user suggests that the location is Ahvaz, in southern Iran, Bellingcat believes that it is more likely to be the Al-Fakkah oilfields in the Maysan Governorate, on the Iran-Iraq border. More details on how this conclusion was reached can be found in the Twitter thread below (which includes a typo, the correct date should be January 2019):

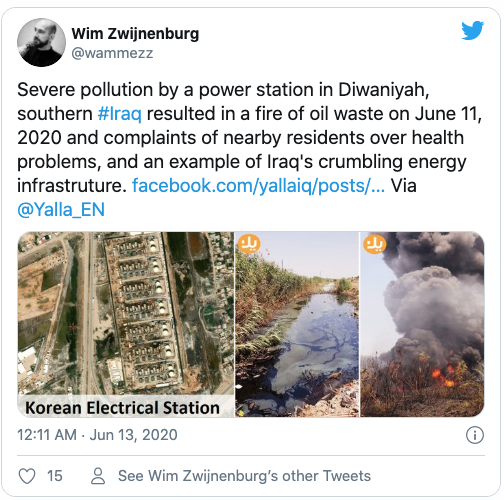

Run-off from refineries, oilfields and power plants is a widespread problem across Iraq. For example, on June 11, oil runoff caught fire near the town of Diwaniyah, capital of the Al-Qadisiyyah Governorate in central Iraq. A Facebook post from Yalla, an independent youth-focused news website, showed the extent of the blaze, to which local residents attributed a rise in health problems.

Shipwrecks, far below

The heavy fighting of the Iran-Iraq War littered the Shatt al-Arab with marine wrecks. From oil tankers to navy vessels, freight ships to fishing boats, they continue to pollute the environment despite attempts over past decades to remove them from the riverbed. In 1989, a year after the ceasefire which ended the war, the the Journal of Commerce reported that 78 wrecks had been cleared.

Shortly after the US invasion in 2003, a UNEP report on the state of the Iraqi environment stated that there are approximately 260 wrecks in the Shatt al Arab, and warning that they are “carrying hazardous cargo including chemicals, crude and refined oil, bunker oil, battery acids, asbestos, other chemicals, short-range missiles and unexploded ordnance.” and funding was put towards removal of those wrecks. This was followed by a UNDP report from 2004, that found hundreds of vessels in and around Basra’s rivers. Sadly the original is not available online, and those reporting on the report draw the content from this 2005 “Warfare: Iraq’s Toxic Shipwrecks’ study in Environmental Health Perspectives, that also provides more insights on the nature of pollution in the river and the Persian Gulf from leaking oil.

In 2005, some online users even took the effort to make an online Google Sight Seeing tour of those shipwrecks visible on satellite imagery, which are today still rusting away, either barely floating or capsized, a dark memory of past wars.

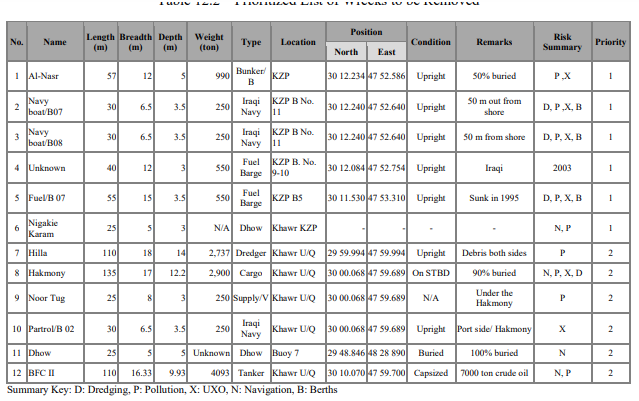

A list of priority wrecks was found in a 2012 report by the Iraqi Ministry of Transport on the development of the Um Qasr harbour in south, noting the many shipwrecks filled with fuel and unexploded ordinance (UXO):

In June 2020, a publication by Iraqi researchers using a sonar radar in a small sub to map shipwrecks in the Shatt al-Arab and identified over two dozen signatures, with almost a dozen confirmed wrecks of ships in the river next to and south of Basra City.

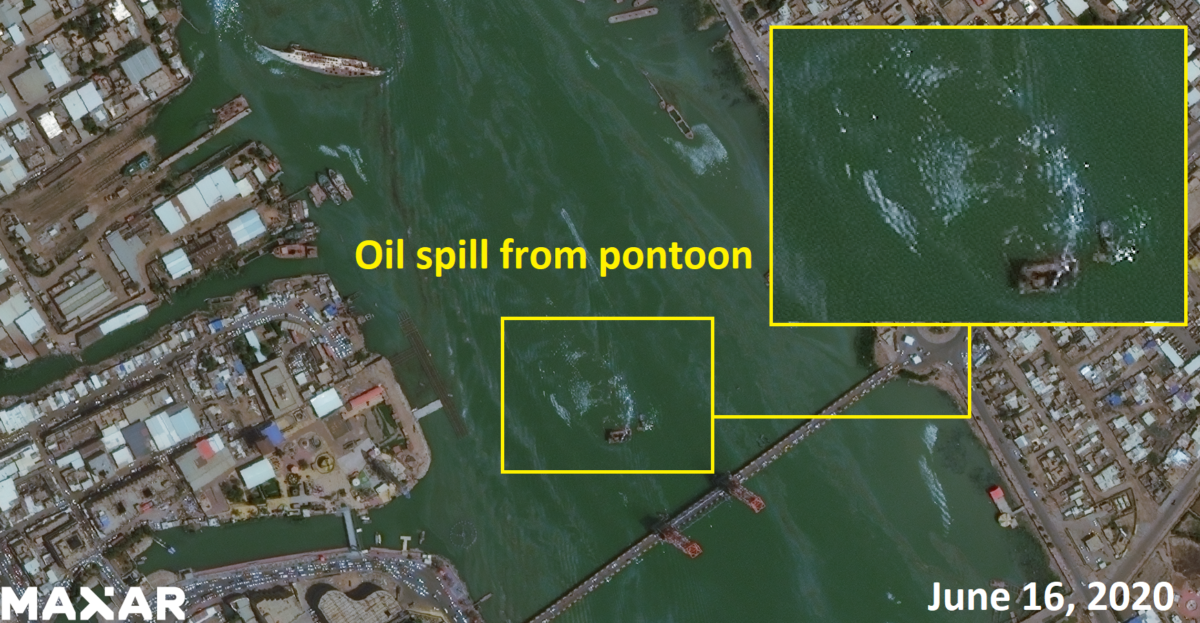

A substantial number of wrecks have now been cleared, yet incidents from this June and July demonstrate how leaking shipwrecks can still contribute to polluted surface water. As noted in Iraq’s first contribution to the Convention of Biodiversity, pollution from leaking shipwrecks can be a direct threat to marine life in these areas as well, and reiterated this message in their latest contribution to the CBD.

On June 15, 2020, Al Rafidain TV alerted the public to another oil spill, due to submerged underwater objects:

A further source of major pollution in the Shatt al-Arab is the dumping of sewage and solid waste.

Successive Iraqi governments have been tasked with addressing the issue, but to little avail. This AP report from 2000, for instance, showing the direct discharge of untreated sewage into the Tigris and Shatt al-Arab outside Basra. Prior to the 2018 water crisis, references to these problems surfaced in practically every relevant government report, including the aforementioned The National Environmental Strategy and Action Plan for Iraq, the joint analysis by UN agencies post-2003, Iraqi submissions on the state of the environment and biodiversity to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the latest being in 2018, to UN Environment post-conflict analysis and UNICEF warnings.

Local NGOs such as Save the Tigris and international networks alike have been raising concerns prior to Basra’s water crisis, most notably on upstream pollution of the Tigris in Baghdad and wider environmental concerns.

A 2013 analysis on Iraq’s water and sewage sector conducted by consultants for Japanese businesses indicated that Iraq produces 580 million cubic liters of waste water on an annual basis, noting that most of its waste water treatment facilities are in ‘various stages of disrepair’. The report provides a bleak reading into a failing government unable to establish a coherent strategy and assign proper budgets to fix its waste water infrastructure. The aforementioned HRW report on Basra’s water crisis, released five years later, suggests that little had changed in subsequent years.

Thus the dumping of sewage in local rivers is a known phenomenon; a clear example of this practice surfaced in July 2020 in Al-Muthanna, a province North-West of Basra. In this video, geolocated and verified by a local Iraqi environmentalist in the town of Rumaythah, its is claimed raw sewage is dumped into a local creek, geo-located in the image below the Tweet.

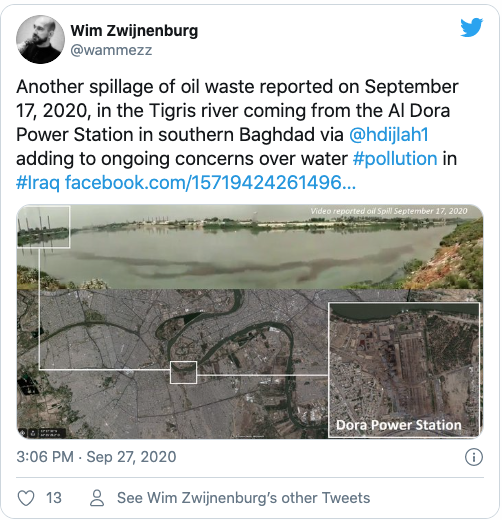

Judging by local media and social media reports, problems with wastewater spillage have continued ever since. According to Humat Dijlah, locals continue to report on wastewater spillages affecting nearby residential areas:

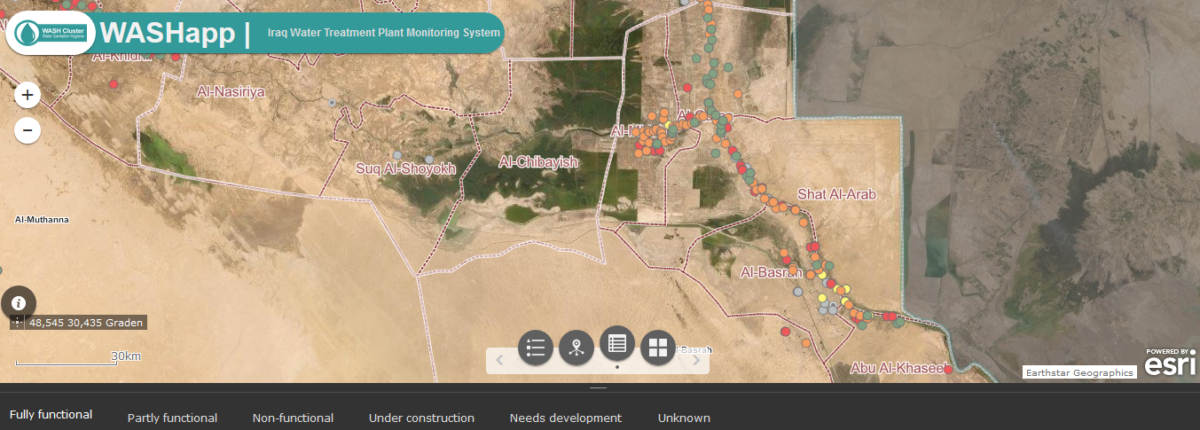

These examples go to demonstrate the ongoing problems with water infrastructure in Basra and the active role of concerned citizens and activists in monitoring the situation. In September 2020, a new visual tool was released by REACH on the water security situation in Iraq, including an online dashboard called WASHapp, with all the 240 known water treatment plants in Iraq and their current status. The screenshot below shows the status of all these facilities in Basra:

Despite efforts by local activists to clean up solid waste in and near the Shatt al-Arab on World Environment Day 2019, incidents continue to raise concerns. That year, the BBC aired a report on how local people took to social media to complain about ongoing waste and water issues; one such video was widely shared on Facebook.

Throughout this year, anonymous Twitter users have continued to report on solid waste problems and failures of sewage treatment in Basra’s Hussein neighbourhood, again indicating the neglect of waste treatment facilities and wider infrastructure problems.

Furthermore, in summer 2020, local media outlet Al Mirbad aired a news report about sewage leakages and lack of waste collection, showing sewage flooding the streets of the Al-Mishraq neighbourhood in Basra. These scenes attest to the fact that more intensive cleanup efforts may be required, especially with the rapid rise of Covid-19 cases in the country.

The fight continuesTwo years since mass protests, the beleaguered people of Basra continue to wrestle with a public health crisis and to fight for a clean and unspoilt Shatt al-Arab. The examples above, whether oil spills, shipwrecks, or contaminated water, attest not only to the scale of their struggle, but to their resourcefulness in identifying concrete incidents of pollution.

There is not only a wealth of information online, but a wealth of tools which can be used to understand it. Geolocation, publicly available remote sensing data and satellite imagery help to piece together a picture which demonstrates the Iraqi state’s failure to seriously tackle the poor state of water infrastructure.

That picture might be a depressing one, but it can also inspire wider calls to take action for environmental protection. Iraqi citizens are already heeding that call online, out of concern for their livelihoods and even their lives. Tied to the security threats which have rocked the country for decades, issues of environmental degradation, pollution and climate change are no longer secondary problems for Iraqis. They are continuing to protest, demanding that the government improve public services and guarantee clean water for all — an even more urgent need during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Source (Click Here)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed