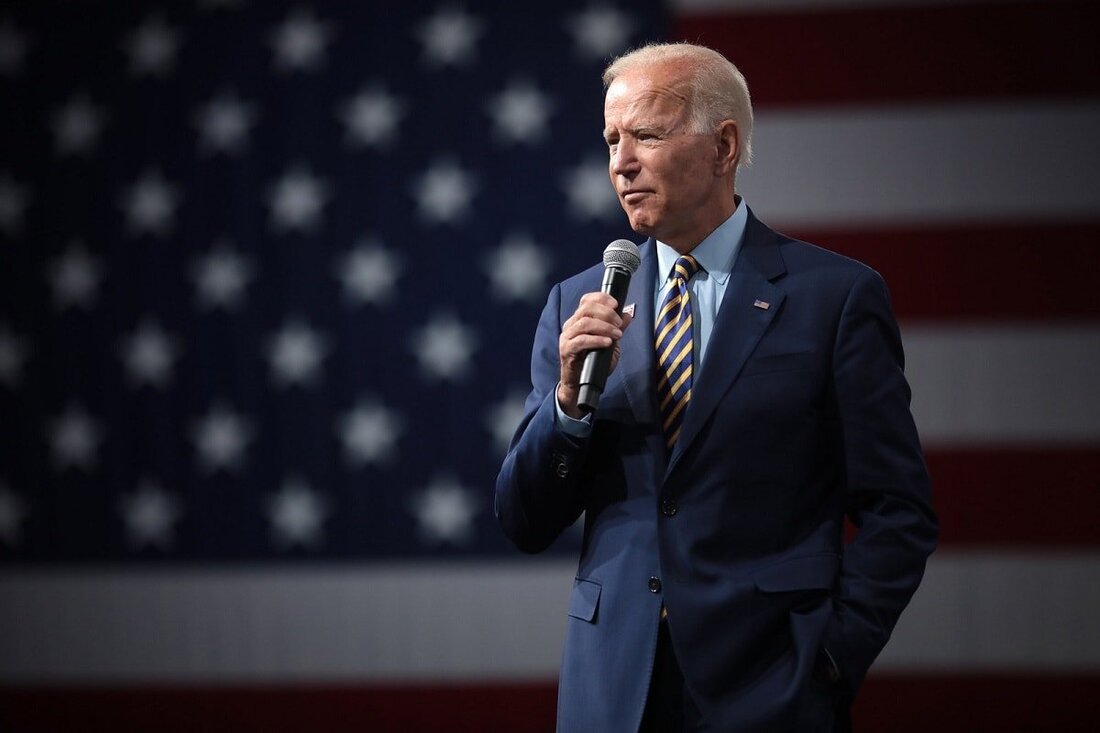

During the campaign, Joe Biden repeatedly criticized the Trump administration’s decision to exit the 2015 nuclear deal and urged a quick renewal to direct diplomacy. Just days after Biden’s inauguration, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan promised to fast-track negotiations. Rather than use Iran’s dire financial straits as leverage, Biden’s team sought to rebuild Iran’s hard currency reserves even prior to any Iranian commitment to return to compliance with the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) or, for that matter, Tehran’s nuclear non-proliferation treaty safeguards agreement.

The White House, for example, pressured Seoul to release $1 billion in frozen Iranian assets to Tehran following an Iranian seizure of a South Korean ship. White House aide Brett McGurk and State Department Iran envoy Rob Malley have likewise sought to pressure Baghdad to release nearly $4 billion from an Iran escrow account that the Iraqi government had established during the Trump administration in order to ensure that Iraq could purchase Iranian fuel while ensuring that the proceeds would not subsidize Iranian terror.

In recent weeks, Malley has traveled to Vienna to renew nuclear talks. His position has shifted quickly from tying the lifting of sanctions to Iran returning to JCPOA compliance to simply demanding a commitment to return to the status quo ante.

The real talks, however, may not be in Vienna and may not involve Malley directly.

This is par for the course for Burns. In 2001, Burns—then an assistant secretary—began secret negotiations with the Qadhafi regime in Libya that he sought to keep secret from many within the State Department. (This was the origin of the controversy at the time over ‘unmasking’ the identity of some involved in negotiations who senior officials did not know had approval to talk to the Libyans). In the last months of the George W. Bush administration, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice sent Burns to meet Iran’s lead negotiator, scrapping an earlier promise that there would be no direct negotiations until Iran committed to suspend uranium enrichment. Burns had not gone rogue—Rice had authorized his meeting—but he does have an unusual knack to take the lead on negotiations with rogue regimes even when other diplomats seek credit or wish to be at the center of substantive talks.

Back to Iraq: While Baghdad makes sense as a locale for negotiations, it is fair for Congress to ask with whom Burns is meeting, his objective, and what Biden or Sullivan authorized him to offer. Equally important, it is worth considering the price of any such meeting. Iraqi Foreign Minister Fuad Hussein lost Iraq’s presidency to current incumbent Barham Salih despite McGurk trying to hand the position to Hussein. By helping broker the U.S.-Iran secret talks, Hussein may now expect as a reward renewed U.S. support for his presidency in Iraq. This would be a high price to pay indeed since Fuad Hussein’s main source of political legitimacy has been as consigliere to Kurdish leader Masud Barzani whereas Barham Salih has proven himself a more able and more consistently pro-Western bridge builder. No single meeting or even series of meetings is worth sacrificing Iraq’s long-term stability or promising its presidency to a man not competent to hold it.

Biden’s enthusiasm for rapprochement is bad enough. That he feels he must keep the real true negotiations secret does not bode well for his confidence that Congress and regional states will find his compromises wise.

Source (Click Here)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed