The then newly-admitted European Union (EU) member went on to command a 9000 strong multinational force that it had contributed 2500 of its own soldiers to. That’s not all. Despite Poles own history of foreign encroachment that has long tormented its people, Poland took up its residency in Baghdad as an occupant force, administering one of four “security sectors” in Baghdad.

“For our freedom and yours” -- Za naszą i waszą wolność -- was the ideological springboard that brought Poland back to Iraq. They were not there to construct infrastructure as they had in the late 60s and 70s, but rather to occupy. Standing idly by was not a choice.

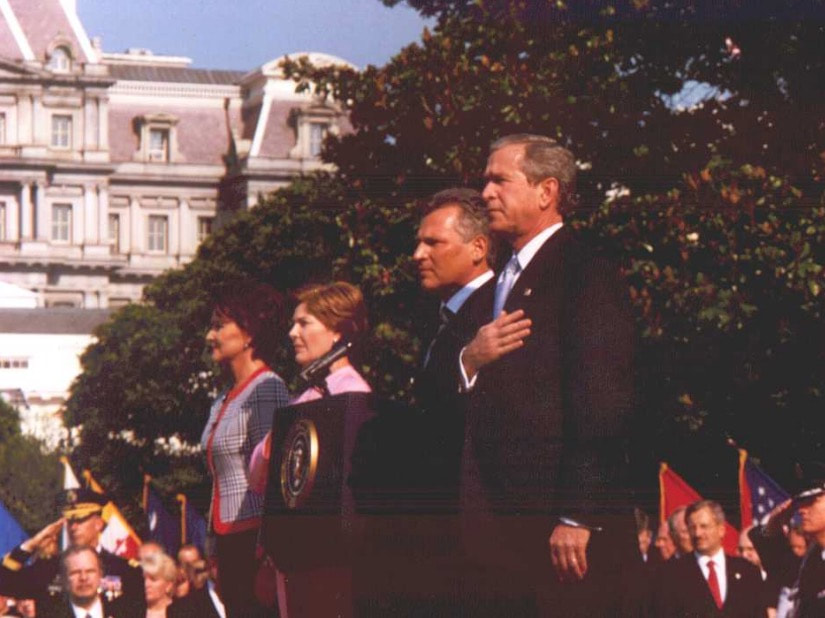

In the lead up to the offensive, President Aleksandr Kwasniewski told the New York Times that “we are more sensitive”, understanding “what it means not to act in the face of a threat” -- with reference to Europe’s policy of appeasement towards Adolf Hitler.

Yet as the war grinded on, Kwasniewski’s unapologetic tone turned remorseful, confessing to French reporters that Poland has been misled, after the myth of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMDs) was laid bare to spectators worldwide.

Poland’s weary attitude towards alliance building (based on its own historical memory) is one. The theme of betrayal of the Polish nation by its western allies (in 1939 and 1945) appears consistently throughout the last one hundred years of Polish history. The memory of this, some argue, informed the decision to not abandon George W. Bush in his hour of need. In assuming a cameo role, Poland was testing its loyalty, although unhesitatingly, towards America.

Their political romance bloomed back in 1999 shortly after Poland and its former rivals were welcomed into the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1999. The moral case for war, however strong, was undermined by the mounting death toll Poland suffered, 22 in total -- exposing the nature of Polish involvement, while dividing public opinion back home. A US embassy cable written back in 2003 underscored the weakness of this rationale, stating that “Graphic images from Abu Ghraib undermine public support in ways that reports of Polish casualties could not … “prompting even long-time advocates” to question Poland’s role.

Poland’s unquestioning endorsement of a ‘military solution’ was therefore matched by indifference toward the philosophical underpinnings of Washington’s military force.

Beyond military favors is talk of strategic decision making on Poland’s part. The fact that its participation in Iraq coincided with its EU membership bid was no coincidence. As a rising middling power -- part of the Rumself defined ‘new Europe’ -- Poland seized a chance others spurned. It hoped that in exchange of its unwavering support, America would stand in as its ‘security provider’.

Private security firm Blackwater's successful rescue mission of Poland’s ambassador to Iraq Edward Piertrzyk is a case in point. Poland also seized its chance to mark itself apart from its regional peers by supporting the war on Iraq. Poland’s own experience with democracy, largely viewed as a ‘success story’, was also packaged to mask these ambitions while it schemed its comeback on the international political stage, propped up by America. In the words of former adviser to the Polish government Leszek Jesień the necessity was driven by the purported duty of sharing with the world Poland’s “recent experience of coming back to democracy”.

However, the honeymoon period as commentators have written, was short lived, with Poland losing more than it bargained for. As Poles back home began to weigh up losses against rewards, pressure over troop deployment grew. Opponents of their country’s imperial venture grew louder, while politicians worked hard to prolong their stay. As other European powers began to withdraw their forces, Poland remained hesitant. Scouting out a role for Polish firms in the reconstruction phase as well as oil stakes may help to explain why. Only after the government filed a formal request urging the president to withdraw from Iraq by October 31, 2007, were years of contemplation laid to rest.

In spite of Poland’s diminishing returns, the former socialist state has maintained ‘friendly’ relation with Iraq. Since its pull out, Poland has kept up the charade with officials from both states shuttling between Warsaw and Baghdad, discussing matters of mutual concern. While Poland’s involvement may not have earned it the profile boost it hoped for, Poles have established a foothold, as an important trade partner with Iraq. Trade deals between Iraq and Poland totalled $500 million in the past year alone.

Despite this, in his latest trip to the Polish capital last November, Iraqi president Fuad Masum called on Poland to cancel the $564 million in bilateral debt Iraq owes. Arms deals between Iraq’s US-backed government and Poland is another basis for their bilateral relations, but one underreported in English-printed press. An Iraqi delegation met a Polish Armaments team (PGZ) in November last year to discuss the trade of armoured T-72 tanks and vehicles.

Training programmes whose details are shrouded in secrecy are performed in Iraq by Poland’s private security firms. The Trojan horse EU diplomats accused Poland of playing was a tool America used to cement its global hegemonic hold, with unintended consequences for all. Poland’s favours and ambitions have gone unrewarded, but in making their decision to back America’s 2003 invasion and subsequent occupation, they have left themselves with little room for manoeuvre.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed