This display of anger accompanied by the words “You dog!” directed at the head of a U.S. president was a moment of shock and reckoning for many Americans. This time, however, it was not popular footage resurfacing just to disappear once again into the Internet. Rather, the tweet was quoted with the caption “Whoever threw those shoes at George Bush should be offered honorary American citizenship” to which al-Zaidi responded with an unmistakably profound retort: “Thank you dear i have the best nationality Iraqi citizen.” In this one sentence, years of war, strife, and struggle; foreign intervention; and deep-rooted nationalism surfaced to reveal the state of the Iraqi psyche.

A region fraught with a lengthy history of foreign intervention, the 2003 U.S. invasion and subsequent attempt to establish democracy in a (geopolitically strategic) country, changed the trajectory of Iraq’s future. This nine-year war heightened sectarian tensions, diminished abilities to intercept a rise in violent extremism, and failed to establish a post-invasion plan to deter Iraq’s transfer from one power’s hands to another’s.

The emergence of Iran’s direct involvement as a tactical player is the result of America’s inability to achieve its goals. Iran has established a political stronghold in Iraq as part of its religious and/or political narrative (read: expansionist blueprint), generating reprisal among Iraqis searching for self-determination. To comprehend Iraq’s ongoing protests, acknowledging the historical politicization of sectarianism, transnational influence, and marked involvement of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps, and yearning among Iraqis for political autonomy is imperative.

From 1980-1988, the newly-established Islamic Republic of Iran was thrust into a war after Saddam Hussein invaded following what many have deemed a series of miscalculations regarding Iran’s vulnerability. For Saddam, the rebirth of this Shia republic as a theocracy—if given the chance—could sway Iraq’s delicate Sunni-Shia balance. Hostilities were born from “centuries-old Sunni-versus-Shia and Arab-versus-Persian religious and ethnic disputes, [and] a personal animosity between Saddam Hussein and Ayatollah Khomeini.” Chiefly, Iraq sought to consolidate its regional power and replace Iran as the ascendant Persian Gulf state; perceiving Iran’s existence as a threat to the pan-Arabism cultivated throughout the Arab world.

The August 1988 UN-sponsored ceasefire ushered in stark regional polarization. Libya and Syria sided with Tehran, while GCC countries—alongside Egypt and Jordan—sided with Baghdad. The conflict fundamentally served as justification for an escalation in Shia-versus-Sunni enmity.

Post-U.S. Invasion

The 2003 U.S. invasion destroyed Iraq’s political and military frameworks. Among the most disastrous American policies was the dismantling and purging of any former member of Saddam’s ruling Baath Party. Marginalizing Sunni men increased sectarian violence, causing Shias to view Iran as their protectorate. By mobilizing the IRGC to occupy the power vacuum left by the American withdrawal, recruitment began among militias loyal to Iran. Since the Islamic Republic of Iran’s (IRI) inception, anti-Shia sentiment has been exploited—portraying Shias as victims and Iran as their savior.

The 2005 Iraqi parliamentary elections were a catalyst for Iranian involvement. With a Shia-controlled majority elected, Nouri al-Maliki was named prime minister—a politician with well-established ties to Iran. Suddenly the world’s only major Shia power had a Shia-led neighbor. Encouraging its closest Iraqi allies—the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI), the Badr Organization, the Islamic Dawa Party, and the Sadrists—to participate in the electoral process, Iran emphasized the importance of a unified Shia vote.

The Badr Organization—overseen by the IRGC—fought alongside Iran during the Iran-Iraq War. “Tehran’s allies played a key role in shaping the 2005 constitution and Iraq’s nascent political institutions, and Iran reportedly tried to influence the Iraqi parliamentary elections in 2005 and 2010, and provincial elections in 2009, by funding and advising its preferred candidates,” Michael Eisenstadt, Michael Knights, and Ahmed Ali write.

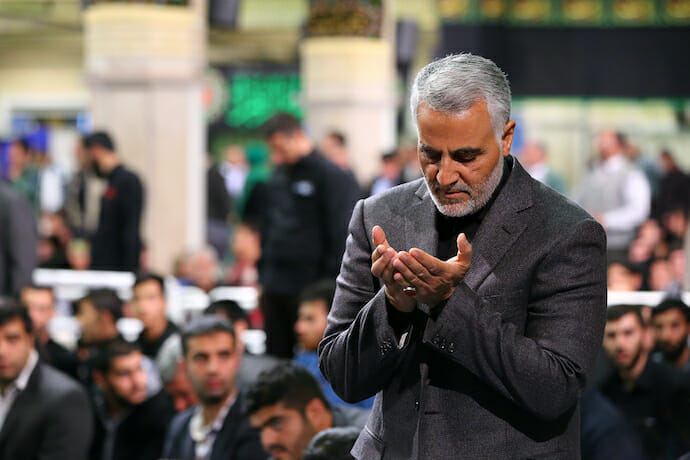

Qassem Soleimani, former Quds Force Commander, assisted in key negotiations to establish Iraq’s government in 2005, allegedly brokering cease-fire deals and persuading ISCI, Dawa, and Sadrists—the eponym for Muqtada al-Sadr, a major Iraqi political and clerical force—to coalesce for the 2010 elections. Indeed, Iran’s connivance in Iraq’s political process showcased its longstanding expansionist ambition to export the revolution to Arab nations through a religious-political movement appealing to the broader Shia community.

Iran’s regional influence has been strategic. On the eve of the U.S. invasion, Iran launched an Arabic-language news channel to emphasize its protectorate narrative. In 2008, Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad visited Baghdad at the behest of Iraq’s Shia parliament—a presidential first since before the Iran-Iraq War. Both Iranian ambassadors to Iraq also served in the Quds Force. Specializing in foreign missions, the Quds Force trains, funds, and provides weapons to Iraqi insurgents, Hezbollah, and Hamas; supports the Assad regime in Syria; and often enlists members from Islamic holy sites, of which the largest recruitment office is located in Mecca. The ambassadors’ appointments “reflect the role Iran’s security services play in formulating and executing policy in Iraq.” After the 2014 election, the Secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council assisted in government reformation.

The Tehran Cables

The publication of leaked documents from Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and Security has shed, with shocking clarity, new light on the extent of Iran’s involvement in Iraq. Known as the Tehran Cables, these communiqués cataloged information from Iranian spies to “co-opt the country’s leaders, pay Iraqi agents working for the Americans to switch sides and infiltrate every aspect of Iraq’s political, economic and religious life.”

The cables revealed just how many senior Iraqi political and military officials maintain close relationships with Iran. Identified PM Abdul-Mahdi as “having a ‘special relationship’ with” the Islamic Republic of Iran; explicated how Islamic Republic of Iran operatives have conducted espionage missions; and how the IRGC has curated high-level informants to obtain critical information on American involvement, missions, and strategies.

Demonstrations

Iran’s endorsement of Iraq’s government and economic structure has been fundamental. Posters depicting the solemn face of Ayatollah Khomeini can be found dotting roadside billboards and strung along gates in Baghdad—a brazen reminder of the foreign intervention at play. Iran’s narrative—particularly through the missions, espionage, and nebulous deals spearheaded by the Quds Force—has furthered factionalism. Indeed, the anti-Islamic State rhetoric touted by IRGC operations has further marginalized Sunnis, who have sought a defense from extremists.

In October 2019, protests erupted in Iraq over rampant unemployment, defective services and infrastructure, and corruption. Youth championed the demonstrations, largely without sectarian undertones or political affiliations. A national appeal for infrastructural repair and job creation led to demands for complete governmental restructuring. In a display of frustration, protestors stormed the Iranian Consulate in Najaf, burning it to the ground—a symbolic attack on the foreign power so entwined in Iraq’s anatomy.

The fervor only intensified when reports emerged regarding Soleimani’s arrival, who—at the first sound of unrest—traveled to Iraq to prevent the ousting of Adil Abdul-Mahdi. As Iran becomes increasingly fearful of neighboring instability, Iranian factions within Iraq are becoming influential players. Though pro-Iranian militias were suspected of aiding in protest suppression, the leaked cables and the demonstrations’ intensity could not protect Adil Abdul-Mahdi and by November 2019, parliament accepted his resignation.

Though Iraq’s leadership has altered, protestors continue to vie for change. The protests have now reached the one-year mark, having tested the fortitude and leadership of Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhimi, who has held office for just over six months. While the COVID-19 pandemic halted gatherings, the anniversary has reinvigorated the fervent assertion of the movement’s vitality.

The protests splintered the fortified foundation of Iranian foreign intervention, and threatening its dominant position. The rampant disaffection has done little to benefit Iran, which struggles to manage dissension within its own borders, as skyrocketing oil prices have exasperated its populace. While Iran has attempted to export the revolution’s ideology to Arab nations for decades, Iran’s Shi’ism rarely appeals to its Arab counterparts. Arab nationalism—regardless of sect—remains forceful, exemplified by the simple and yet profound sentence uttered by al-Zaidi on Twitter.

A rise in rhetoric regarding a ‘Shia Ascendency’ and ‘Shia Power’ must be solely attributed to Iran’s foreign intervention. Although combatting anti-Shia sentiment and championing a new era of pan-Islamism fuels Iran’s operations, its goals transcend solely assisting Iraq’s ‘Forgotten Muslims.’ Good relations with its Arab neighbors will increase regional hegemony and grant Iran leverage in its exchanges with other world powers. Understanding the political strategies employed to enhance Iran’s sphere of influence elucidates how foreign intervention affects ideological cleavages and causes mass discontent—illustrating just how entangled a foreign power can become when sectarianism is the leading narrative from both sides of the divide.

Source (Click Here)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed