BASRA, Iraq - On the walls of Basra children’s cancer hospital hang photos of some of the youngsters who’ve been treated there. Most are smiling. Some of the portraits have a black stripe in the upper left corner. Those are pictures of children who passed away.

Hesham Abdullah says he quit his office job to care for his son Mostafa, 14, and sold his house and all the family’s valuables to pay for treatment. With no medical insurance, he estimates he has spent at least $120,000 on black market medicines and trips to overseas clinics. His family of five had to move in with his brother.

“It’s worth it. I’d sleep in the street in return for a pain-free moment for him,” said Abdullah. “But this is not something any individual can afford. This is something the state should handle.”

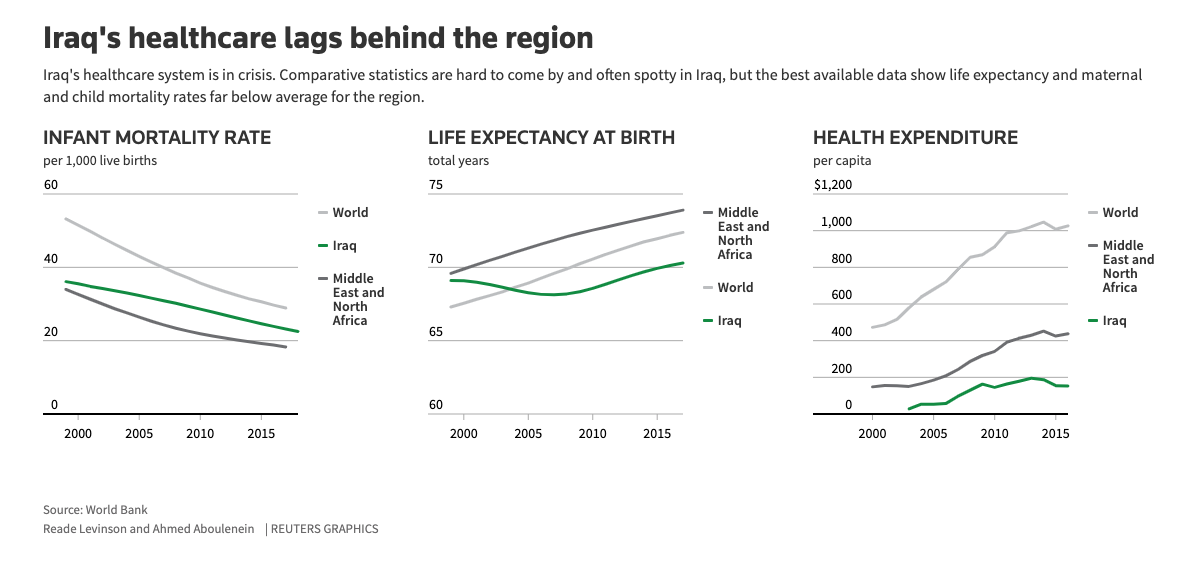

To understand the collapse of Iraq’s healthcare, Reuters spoke to dozens of doctors, patients, officials and private investors and analyzed government and World Health Organization data. The story that emerges is complex. Over the past three decades the country has been ravaged - by war and U.N. sanctions, by sectarian conflict and the rise of Islamic State. Yet even in times of relative stability, Iraq has missed opportunities to expand and rebuild its healthcare system.

“Health is not a priority and the indicators show that. The government did not give healthcare what it deserves,” Alaa Alwan, Iraq’s health minister, told Reuters in August. Alwan, who has also served in senior roles at the World Health Organization, resigned as minister the following month, after just one year in office, citing insurmountable corruption and threats from people opposed to his reform efforts.

“I am here today because my mother is suffering from cancer and she cannot find even the most basic treatment,” said teacher Karrar Mohamed, 25 years old, who also lost his father to the disease.

Mohamed was speaking in early November, surrounded by dozens of young men brandishing sticks and wearing gas masks. They’d blocked a central Baghdad bridge and were getting ready to square off against heavily armed police. Since Oct. 1, security forces have killed almost 500 protesters and wounded thousands, according to a Reuters tally. The protests led Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi to resign in December.

Mostafa lay on a bed in his uncle’s living room in Basra when a Reuters reporter visited in the spring of 2019. His face contorted with silent pain. He couldn’t sit comfortably because of the lump on his back. It began with a simple leg pain in 2016. Mostafa was initially misdiagnosed with joint inflammation. By the time the tumour was detected, his health was worse. Doctors determined he was suffering from sarcoma, a cancer of the connective tissue.

Mostafa started treatment at the Basra children’s cancer hospital.

The hospital is very short of space. Six beds are crammed into each room and every bed is occupied. With just 1.2 hospital beds per 1,000 people, Iraq lags the region. Mothers sleep on the floor, beside their sick children. Fathers sleep in an adjacent trailer – Iraqis call it a caravan. Even the emergency rooms have been repurposed to accommodate more patients. Administrators say the hospital may soon have to expand into storage sites.

Parents complain that the space crunch is not good for children who have reduced immunity due to chemotherapy, but they know if the hospital restricted occupancy most children would not be admitted.

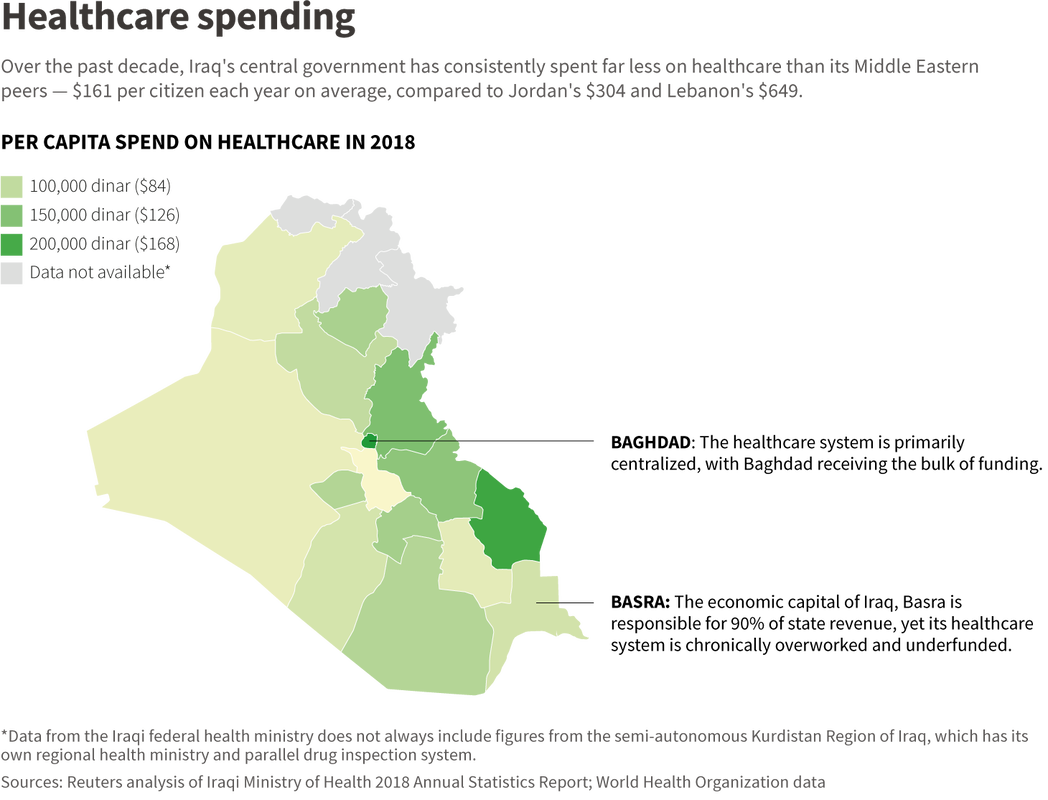

Nor can the war with Islamic State be blamed for the lack of beds and staff. In contrast to provinces that were devastated by the extremists’ advance, Basra witnessed no fighting. Patients and doctors point to corruption and mismanagement at federal and local levels.

More than 85%Of essential drugs were in short supply or unavailable in Iraq in 2018

Between 2015 and 2017, the government spent an average of $71 per citizen on healthcare in Basra, Reuters found, half the national average. Basra is desperately short of vital medical equipment, with just three CT scanners and one MRI unit per million residents, a fraction of the average rate of 34 CT scanners and 24 MRI units for developed countries.

Abdullah worries about the quality of care at the Basra children’s cancer centre. The hospital’s chief administrator, Ali al-Eidani, said the clinic needed more than four times the funds it received from the health ministry in 2019 to operate effectively. The hospital does not have a PET scan machine, used to help detect and diagnose certain cancers, or enough cancer drugs.

To keep his hospital going during drug shortages, Eidani holds fundraisers. These get him in trouble with the authorities, who have investigated him for corruption multiple times, and each time let him off with a warning. Nothing too serious, he says, adding a solemn “yet.” He says his bosses understand he must improvise to keep the place running so they investigate him, but don’t take it further. Health ministry officials acknowledged that such situations sometimes arose.

Bending the rules

Funding is not the only issue.

Government rules dating back to the 1970s bar doctors like Eidani from purchasing equipment or medicine from the private sector. Instead, he must receive medicine directly from the health ministry in Baghdad, which often doesn’t have enough to give.

Eidani said that if he played by the books, kids would simply die.

Instead, he resorts to a loophole: buying drugs from the semi-autonomous Kurdistan Region of Iraq, which has its own health ministry and parallel drug inspection system. Because the drugs have been inspected and approved by a government body, they are considered legally procured.

Healthcare is better in Kurdistan. The region was unscathed by the U.S.-led invasion in 2003 and escaped the devastation of the civil war that followed. It has 15% to 20% of Iraq’s population yet houses a quarter of Iraq’s cardiovascular and rehabilitation centres and a third of the diabetes centres. Where the rest of Iraq has 1.1 hospital beds and 0.8 doctors per 1,000 people, Kurdistan has 1.5 beds and 1.4 doctors.

The government imports drugs and medical equipment through the State Company for Marketing Drugs and Medical Appliances, known as KIMADIA. Its head insisted the relationship with pharmaceutical firms is good, but he also conceded KIMADIA is outdated and underfunded and often fails to meet demand.

“It takes time to even study what drugs we are lacking,” said Mudhafar Abbas, brought in by ex-minister Alwan to streamline KIMADIA. “We have a centralised bureaucracy.”

Pharmacies are flush with smuggled drugs that could be past their expiry date or unsafe. Iraq cannot count on its local industry to produce medicines, either.

It’s a far cry from the 1960s and 1970s when Iraqi healthcare was the envy of the Middle East. Iraq was the second country, after Egypt, to enter the pharmaceutical industry. Two large state-owned factories now stand as a monument to the country’s decline. The first, in Mosul, was devastated by the Islamic State takeover. The second, in Samara, north of Baghdad, operates using decades-old equipment. Women scoop up blister packs and bind them together with a rubber band. Men box the bundles by hand.

“A long war with Iran, sanctions for 13 years, the war in 2003, this of course has an effect,” said Abdulrahman. “Any country without political and economic stability will see a decline in industry.”

There are 17 privately owned factories, but they also make basic medicine with outdated technology. Corruption, high taxes, an unreliable power grid, a poor supply chain, and dire security conditions have set the industry back decades, medical professionals say. Iraqi firms cover less than 8% of market need, Abbas said. They lack raw materials, technology and equipment.

“SDI used to be a pioneer,” Abbas said. “We used to export to Eastern European and Arab states. Now look at us.”

A breakdown of trust

Iraq has some of the lowest numbers of doctors and nurses per capita in the region - fewer than significantly poorer nations like Jordan and Tunisia.

In 2018, Iraq had just 2.1 nurses and midwives per thousand people, less than Jordan’s 3.2 and Lebanon’s 3.7, according to each country’s estimates. And it had just 0.83 doctors per thousand people, far fewer than its Middle Eastern counterparts. Neighbouring Jordan, for example, has 2.3 doctors per thousand.

Life wasn’t rosy for doctors under Saddam Hussein, doctors are quick to point out. The U.N.’s oil-for-food program provided Iraq with a significant amount of humanitarian aid, including medicine, in exchange for Iraqi oil. Nevertheless there were drug shortages and terrible pay. Doctors were seen as a valuable commodity and barred from travel.

“But at least doctors were protected,” said one physician. “There were no attacks.”

According to Iraq’s medical association, at least 320 doctors have been killed since 2003, when U.S.-led forces toppled Saddam, ushering in years of sectarian violence and Islamist insurgencies. Thousands more have been kidnapped or threatened. Medical professionals steadily left the country under Saddam – many paid smugglers or made perilous journeys. After the American invasion, they began migrating en masse, leaving the public healthcare system ill equipped to treat Iraq’s 38 million people.

Medical association president Abdul Ameer Hussein put it simply: “There aren’t enough doctors and hospitals to deal with the number of patients.”

The healthcare crisis has resulted in a breakdown in trust between doctors and patients. It’s not uncommon for a patient’s tribe to attack a doctor if anything goes wrong during treatment.

“When someone dies, we call the police first, before we tell the family, just in case,” a young former doctor told Reuters in Baghdad. Around 20% of his former colleagues have turned to academia, he estimated. Teaching is safer and more respectable than practicing medicine, he said.

Alaa Alwan, Iraq’s former health minister

Iraqi doctors make just $700 to $800 per month on average, and many seek out second jobs in the private sector to supplement their low income. Most young doctors are overworked, putting in 12 to 16 hour shifts every day. Some take kickbacks to prescribe certain drugs, physicians told Reuters.

Many senior doctors refer patients they see in the morning at public hospitals to their own private practices to boost earnings. This further erodes patients’ trust in the public sector, doctors, patients, and health rights advocates say. The long workdays impact performance, leading to more mistakes and inviting more attacks.

Some doctors purchase medicine for their patients out-of-pocket, either out of moral obligation or fear of attack. The practice is illegal because drugs administered in hospitals must come from the hospital store. And it comes with potential jail time.

In September 2019, hundreds of doctors took to the streets of Baghdad demanding better pay and conditions, mere days before large-scale protests swept the country, an explosion of anger over dire public services and official corruption. Young doctors could be seen administering treatment to wounded protesters in the capital’s central Tahrir Square.

‘No one empathises’

Faced with ill-equipped hospitals and medicine shortages at home, many cancer patients are spending thousands of dollars to seek treatment abroad, in Lebanon, India, Jordan, Iran and Turkey.

Amer Abdulsada, who directs Iraq’s medical evacuation program, said Iraqis spent $500 million on healthcare in India alone in 2018. That year, the Indian government granted about 50,000 medical visas to Iraqis, he said.

Reuters spoke to 11 current and recovering cancer patients who said they spent thousands of dollars on cancer treatment abroad. Many had spent their life savings, only to return to find maintenance therapies unavailable. Those like the Abdullahs, who can no longer afford to travel, spend what little money remains on black market medicines.

Still, the family had enough money saved to fly Mustafa to India eight months later, when his health took a turn for the worse. The trip cost about $16,000 and yielded no improvement.

A later trip to Lebanon - the only time Mostafa received proper treatment, said his father - was possible only after a generous donor paid for it out of charity. The trip cost $7,000. The family couldn’t afford to send him again.

“I am at the end of my string. What else can I do? I have no resources,” said Abdullah.

Drugs were his biggest expense, he said, many purchased from Lebanon because local alternatives are not as effective.

In total, his son’s treatment was costing about $3,000 a year. Abdullah had to quit his office job to take care of Mostafa full time, turning to odd jobs that brought in about $640 to $720 a month.

Things were better under Saddam, said Abdullah. “There was action back then. Now nothing happens. No matter how much you suffer, no one cares, no one empathises,” he said. “Does the state not have mercy?”

In 2019, the ministry enacted reforms to allow business people without medical backgrounds to own hospitals. Health officials estimate the private sector was responsible for adding 2,000 hospital beds to Iraq’s capacity in the first six months of 2019, an increase of 4%. The National Investment Commission (NIC) has introduced several incentives to lure foreign investment. These include a 10-year tax break, the ability to hire foreign workers, customs and duties exemptions, the right to repatriate capital and profits, easier visa and residency processes, and land lease allowances.

But it has not been enough. Drawing investors to Iraq remains a hard sell. Iraq’s financial and political instability is a big impediment. When the new, government-built manufacturing facility to make cancer drugs in Mosul was bombed in 2017, images of the rubble became searing reminders of the region’s risks. There isn’t a stable banking sector. Powerful factions in government fight over resources and make it difficult to get things done.

“There is no foreign investment in the health sector,” said medical evacuation program director Abdulsada. “Foreign investment needs infrastructure. We lack electricity, security. Our banking sector is not equipped for global finance, our borders are not controlled. These are all problems out of the ministry’s control.”

Abandon all hope

Mostafa winced with pain every few minutes, but he rarely made a sound, brave like a “lion,” as his father put it when Reuters returned to the family home in January of this year. The boy followed the conversation in silence, interjecting occasionally to correct a date or a drug price.

Above him hung a series of portraits: Mostafa in his school uniform, when he could go to school and still had hair; in a dapper suit and tie.

He couldn’t play outside, his father explained. He couldn’t exercise. Instead, Mostafa would stay home playing video games on his smartphone. Abdullah no longer dared hope that Mostafa would be cured. All he wanted, he said, tearfully, almost pleading, was for his son to be comfortable and not live in pain.

“I don’t even want a cure, or anything,” Abdullah said. “Just for him to be able to sleep for one night.”

In the early days of February, Mostafa passed away. His picture has not gone up on the hospital wall. Only survivors’ photos are added now.

BAGHDAD - Iraq’s Ministry of Health is turning to private business to help shoulder the cost of upgrading equipment and services.

Among them is Rafee al-Rawi, the scion of an old Sunni family, who promises to revolutionise cancer treatment in Iraq. Rawi is a pathologist by training and now lives in Dubai. He owns a medical devices supplier, an insurance company, a cardiovascular treatment centre in Baghdad and one of the few private pharmaceutical companies in Iraq, making him the country’s closest thing to a healthcare mogul.

For his latest venture, Rawi and his business partners have put $50 million into the Andalus Hospital and Specialized Cancer Treatment Center, a 140,000 square-foot hospital on the eastern side of Baghdad. The hospital began accepting its first patients in the summer of 2018 and is slated to fully open in April 2020. Rawi estimates he and his business partners will invest another $100 million in the hospital. The project is part of a joint venture with Healthcare Global Enterprises, the largest provider of cancer care in India.

Rawi says the hospital has all “the latest models known to medicine,” including a mammography machine, PET and CT scanners to detect cancers and an MRI machine, the type of expensive medical equipment in severely short supply across Iraq. The centre’s crowning achievement is its cyclotron, an 8,300-tonne particle accelerator housed within steep slabs of white concrete. The cyclotron will produce a radioactive substance called fluorodeoxyglucose, or FDG, used to identify cancer cells during medical imaging. FDG is very hard to import due to its very short half-life.

Sami al-Araji, chairman of the National Investment Commission, told Reuters that people like Rawi are central to reforming healthcare. The health ministry also hopes centres like Rawi’s will save the government money it currently spends on a medical evacuation program to send certain patients abroad for diagnoses and treatments that are unavailable locally. Since 2013, Reuters found, the government has sent more than 14,500 patients abroad for cardiac, bone marrow and ophthalmology treatments.

“If successful we will cover drugs for 70-80% of cancers affecting Iraq. Within that 70-80%, we will be able to cover 100% of need. Iraq is spending $80-84 million now, we can reduce it to $30-34 million,” he told Reuters.

For Hikma, it is part of a wider Iraq strategy, its Executive Vice Chairman and President of MENA Mazen Darwazah said. The company is working with several producers to release local versions of their products on the Iraqi market.

Iraq’s healthcare has fallen far

SAMARA, Iraq - Fifty years ago, a much richer Iraqi government spent lavishly on health funding. The state company responsible for drug imports, known by its Arabic acronym KIMADIA, enjoyed such a close relationship with the world’s top drug manufacturers that it would fax orders directly and shipments would arrive before a formal contract was drawn up.

In sharp contrast to the company’s heyday in the 1970s and 1980s, today’s KIMADIA does not have nearly enough money to cover Iraq’s pharmaceutical needs.

In 2018, the state budget allocated $800 million for drugs. KIMADIA blew through it and accrued an additional $455 million in debt to pharmaceutical companies, in the end purchasing just 12% of the 535 drugs on its essential medicines list in large enough quantities to meet demand, said KIMADIA chief Mudhafar Abbas.

The next year, in response to pleas by the health minister at the time, Alaa Alwan, for additional funds, the government increased KIMADIA’s budget to $1.27 billion. But once the agency settled its debts, this left roughly the same amount of money as the previous year; $810 million.

It was only due to smarter purchasing decisions and a crackdown on waste that procurement improved, officials say. Pressed by the continued lack of resources, the ministry also drew up emergency direct purchase deals with other governments including those of Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon, Iran, and India, and relied heavily on the WHO and UNICEF. All this work meant that in 2019, the government secured 235 drugs, 52% of its needs.

The budget crunch of the past two years hit cancer medicines the hardest, Reuters found, based on interviews with officials and an analysis of KIMADIA procurement documents. Cancer medicines, especially some chemotherapy cocktails, are among the most expensive medicines to buy.

In 2018, the Iraqi government purchased just 4 of the 59 core medicines the World Health Organization considers essential for cancer treatment. In 2019, the government purchased 37 of the 59 listed medicines, or 63% of the total recommended. Much of what did not get purchased were chemotherapy medications like procarbazine and fludarabine that target blood cancers like leukemia and Hodgkin lymphoma, diseases that are notoriously difficult to treat.

Even private importers struggle to get drugs into Iraq, Reuters found. Product registration rules have changed three times in the last five years alone, according to importers. It takes nine months to get a factory registered with the health ministry and two years for a drug.

When Islamic State took over an international road linking to Jordan, truck drivers were stopped by the militants and forced to pay tolls, for which they got receipts. By the time foreign companies had worked that into their business models, the government informed them paying the “toll” constituted funding terrorism.

They turned to the sea. Authorities at the port of Basra demand bribes of $30,000 per container to let drugs in, even if the paperwork is in order, several importers interviewed by Reuters said.

Many see no incentive to do things above board.

“You have to have someone to protect you,” said one importer, who requested anonymity.

As a result, over 40% of medicine in the market is smuggled from countries including Turkey, Iran, Jordan, Lebanon, India and China, according to public statements from health officials.

“The state does not control the borders fully. It’s not just counterfeit drugs being smuggled in, but even legitimately registered drugs, as some companies try to dodge fees or taxes. This is all part of the state of pharmaceutical chaos we are experiencing,” said KIMADIA chief Abbas.

He estimates that Iraq has a $4-5 billion pharmaceutical market, with KIMADIA accounting for just 25%.

Source

RSS Feed

RSS Feed