Less than two years later, President George W. Bush launched a ruinous war in Iraq based on a far greater intelligence failure, one that saw the CIA, Pentagon and other agencies effectively make up the evidence that the White House sought to justify invading a country that had not attacked — or even threatened to attack — the United States.

The serial mistruths, mistakes and misperceptions about Iraq’s supposed weapons of mass destruction and alleged support for Al Qaeda are laid out in devastating detail in Robert Draper’s authoritative new book, “To Start a War: How the Bush Administration Took America Into Iraq.”

This is well-trod history, but Draper mines newly declassified documents and tracks down previously unavailable CIA and Defense officials to flesh out the sordid story of the run-up to the March 2003 invasion, the start of a grinding conflict that would last eight years and claim nearly 4,500 American lives.

Unlike President Trump, who utters falsehoods daily, Bush was a true believer — which is exactly what made him impervious to conflicting evidence or doubts about the supposed Iraqi threat.

That folly has given Americans just cause to question U.S. intelligence estimates and, perhaps worse, has gifted Trump with a regular foil for jabs at experts and specialists even in his own administration. The erosion of trust that fueled his base is just one of the many poisonous after-effects of the war.

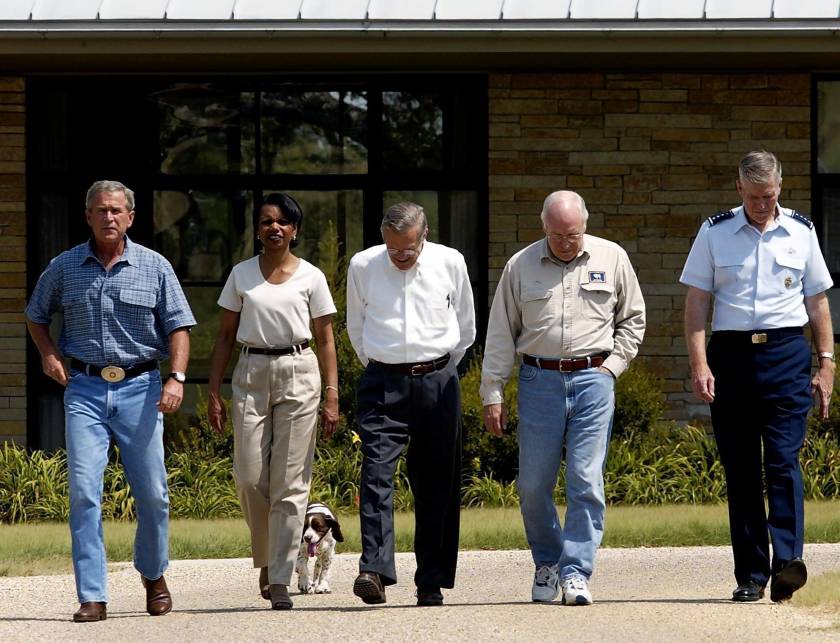

The road to that war began a few days after the 2001 attacks, when Vice President Dick Cheney led his aides to CIA headquarters in Virginia. The nation’s top spy agency was frantically searching for a follow-up assault by bin Laden, who was based in Afghanistan.

But Cheney insisted the CIA needed to focus on Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, despite the CIA briefer’s conviction that there was no evidence of Iraqi involvement in the attacks. As one later said, it was like asking, “Did Belgium do this?”

Over the next year, Cheney and other ideologues would push their bogus theory, as well as increasingly dire but equally false claims that Hussein had secretly produced and stockpiled an arsenal of nuclear, biological and chemical weapons.

Bush needed little convincing: he had ordered up Iraq war plans only two months after the Sept. 11 attacks. As Draper writes, the rush to war was driven by fear, not hard intelligence, and “by imagination, not facts.” It was thus difficult for critics to push back when Bush warned, in October 2002, that “we cannot wait for the final proof — the smoking gun — that could come in the form of a mushroom cloud.”

Yet Iraq had no nuclear program, no poison gases, no shells filled with deadly viruses. U.N. inspectors had scoured the country for months, but their failure to find illicit weapons was viewed in Washington only as proof that Iraq had cleverly hidden them.

Was Iraq in league with bin Laden, as Cheney claimed? An Al Qaeda operative confessed under torture by Egyptian officials that “he had heard from an unnamed associate” of such a link. The coerced, third-hand and uncorroborated claim was enough for the White House, even though it was later deemed false.

The White House also embraced a single-source report from an unnamed informant who told Czech intelligence that he was “70% sure” that Mohammed Atta, one of the 9/11 hijackers, had met with an Iraqi diplomat in Prague in April 2001.

FBI records showed that Atta was stateside during the alleged meeting, and the Iraqi diplomat was not in Prague. But White House demands for details on Atta’s whereabouts led one exhausted CIA analyst to respond tersely, “He’s still dead.”

Intelligence collection is a vast maw, and as one former CIA official told Draper, “You can always find what you want somewhere” amid the conflicting statements, unverified sightings, ambiguous imagery and likely falsehoods. That was especially true of the ultimate justification for the war — Hussein’s supposed weapons of mass destruction. Warnings were dismissed, supportive evidence barely examined, careful analysis cast aside.

A Pentagon memo to Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld in mid-2002 warned that U.S. intelligence on Iraq’s WMD programs was perhaps 90% “incomplete,” for example. He shelved the memo.

Administration claims that Iraq sought to buy yellowcake uranium from the African nation of Niger were laughably easy to disprove: A quick check on Google showed that the supposed letter of agreement was a fraud.

But the White House was not deterred. Most famously, the CIA championed an Iraqi engineer code-named Curveball who told German intelligence that Saddam could churn out anthrax, smallpox and other deadly biological agents on trucks. No wonder spies couldn’t find them!

The Germans warned that Curveball was unreliable and that no evidence backed up his claim; the CIA wasn’t allowed to interview him. But his imaginary mobile germ factories became a linchpin of the tissue-thin U.S. case for war. A year after the invasion, the CIA determined that Curveball was a fabricator, just as the Germans had claimed since 2001. (Full disclosure: Draper interviewed me and cites my book on the Curveball case.)

And on it went. The errors and deceit multiplied, as did rosy predictions of being greeted by the Iraqis as liberators. U.S. intelligence agents flooded into Iraq after the invasion to hunt for WMD — and found nothing.

It got worse. The Pentagon pushed the State Department aside in planning for the postwar period and then stood back as Iraq erupted in violence. A U.S. order to disband the Iraqi army planted the seeds of the insurgency and civil war that followed.

Bush ultimately bears the blame. He relied on a national security team who believed they should support his judgments, not question them. Congress embraced the faith-based intelligence, and so did a cheerleading media.

Draper has written the most comprehensive account yet of that smoldering wreck of foreign policy, one that haunts us today.

Source (Click Here)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed