WASHINGTON—Army chief of staff Gen. Ray Odierno issued the marching orders in the fall of 2013. Some of the Army’s brightest officers would draft an unvarnished history of its performance in the Iraq War.

A towering officer who served 55 months in Iraq, Gen. Odierno told the team the Army hadn’t produced a proper study of its role in the Vietnam War and had to spend the first years in Iraq relearning lessons. This time, he said, the team would research before memories faded and publish a history while the lessons were most relevant.

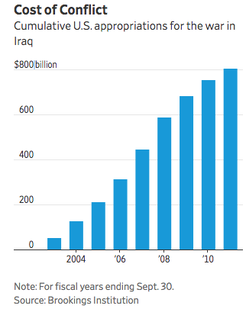

It would be unclassified, he said, to stimulate discussion about the intervention--one that deepened the U.S.’s Mideast role and cost more than 4,400 American lives. He arranged for 30,000 pages of documents to be declassified. For nearly three years, the team studied those papers and conducted more than 100 interviews.

A working cover of the Army report.

A working cover of the Army report. The study’s title: “The United States Army in the Iraq War.”

It has yet to be published.

Gen. Odierno retired before the team could finish the history, which then became stuck in internal reviews and procedural byways.

Under new Pentagon leadership, Army priorities changed from counterinsurgency to countering powers such as Russia and China. Senior brass fretted over the impact the study’s criticisms might have on prominent officers’ reputations and on congressional support for the service.

The study’s very existence is little known outside the Army. The Wall Street Journal pieced together its history through dozens of interviews with former and current officials familiar with the effort, and from reviews of internal memorandums and emails.

In the past few months alone, Army officials debated whether the study should be embraced or disowned. After a high-level review last month, Army officials issued instructions to remove a foreword noting the study had been “commissioned” by the Army and to scrub it of other signs that it had top-level sponsorship.

After the Journal last week asked Gen. Odierno’s successor as chief of staff, Gen. Mark Milley, about the Army’s handling of the study, he reversed those moves and vowed to write his own foreword. He says that although the study isn’t an official history and has gaps in areas such as special operations and enemy activities, the study team “did a damn good job.”

“We owe it to ourselves as an army to turn the lessons learned as quickly and as accurately as we can,” he says, “understanding that they are not going to be perfect.” He says he hopes to publish the study by year’s end.

The saga shows the Army’s difficulty in engaging in the self-criticism needed to improve its military performance, say some familiar with the effort, including Frank Sobchak, the study team’s final director, who retired as a colonel in August.

“We worked tirelessly for three years to complete a scholarly product that captured the war’s lessons in a readable historical narrative,” he says. “That the Army was paralyzed with apprehension for the past two years over publishing it leaves me disappointed with the institution to which I dedicated my adult life.”

One mistake, the study found, was the decision by Gen. Peter Schoomaker, here in 2004, to proceed with a restructuring of Army combat brigades. PHOTO: BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/GETTY IMAGES

One mistake, the study found, was the decision by Gen. Peter Schoomaker, here in 2004, to proceed with a restructuring of Army combat brigades. PHOTO: BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/GETTY IMAGES

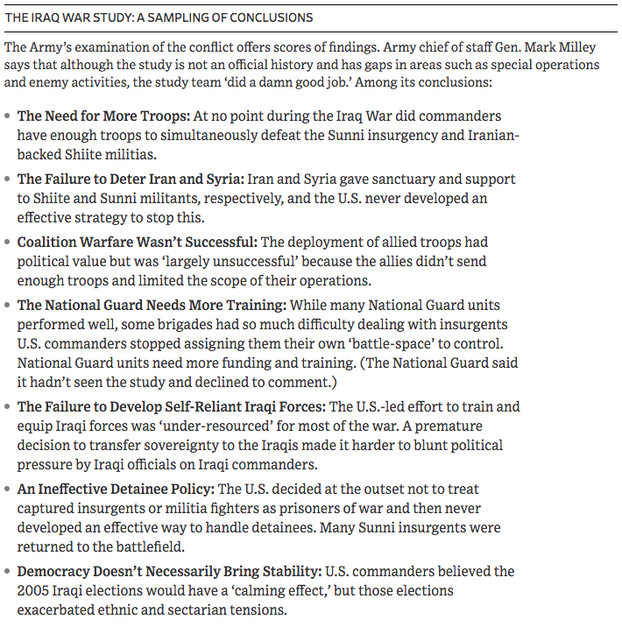

The study asserts that senior U.S. officials continually assumed the military campaign in Iraq would be over within 18 to 24 months and didn’t deploy enough troops. It concludes that in planning the invasion, U.S. officials assumed neighboring states wouldn’t interfere and didn’t develop an effective strategy to dissuade Iran and Syria from supporting militants.

It says the Army made mistakes, such as when then-Army chief of staff Gen. Peter Schoomaker decided to proceed in 2003 and 2004 with a restructuring of Army combat brigades. That meant the Army had fewer active-duty brigades to send to Iraq at a critical time, the study found, forcing it to rely on less proficient National Guard units.

Gen. Schoomaker, who retired from the Army in 2007, says the restructuring enabled the Army to eventually expand its inventory of brigade combat teams. The National Guard said it hadn’t seen the study and declined to comment.

Another mistake, the study says, was consolidating U.S. forces on large bases, a decision by Gen. George Casey, who led U.S. and allied forces in Iraq from 2004 to 2007 before becoming Army chief of staff. That led to a security vacuum around Baghdad that militants filled, the study states.

Gen. Casey didn’t respond to requests for comment. In his own Iraq War history, he said his goal was to shift responsibility for securing the country to the Iraqis.

The study team was led by Col. Joel Rayburn, who worked for Gen. Petraeus in Iraq and wrote a book on Iraqi politics before joining President Trump’s National Security Council. Now a State Department envoy on Syria and retired from the military, he declined to comment.

Col. Sobchak, who joined the project after a Special Forces career, took over the team’s leadership from Col. Rayburn. The remaining authors, who all served in Iraq, hold doctorates in history, international affairs or public administration, including Col. Matthew Zais, now the NSC’s director for Iraq.

War Footing

The invasion of Iraq began on March 20, 2003, and within two months, there were 150,000 U.S. troops in the country.

Some Army officials foresaw trouble if the study wasn’t published before Gen. Odierno retired, which he did in August 2015. Conrad Crane, chief of the historical services division for the Army Heritage and Education Center, a branch of the Army War College, wrote to the team in July 2015 after viewing a draft, saying: “You need to get this published while you still have GEN Odierno as a champion. Otherwise I can see a lot of institutional resistance to having so much dirty laundry aired.” Mr. Crane says he stands by his email.

Change of guard

With both volumes written by the summer of 2016, publication decisions fell to Gen. Odierno’s successor, Gen. Milley, who led a brigade in Iraq and held a more senior command in Afghanistan. “Gen. Milley was very concerned given sensitivities in the wonderful city of Washington, D.C.,” says Gen. Dan Allyn, Army vice chief of staff at the time and now retired. “Clearly, there were senior leaders who were in position when these things happened, and there were concerns on how they were portrayed.”

Gen. Allyn says Army leaders had to balance these sensitivities with the need to share the war’s lessons and that he favored publication.

The study team hoped to unveil the first volume at an October 2016 Army convention and the second a few months later. It would have two forewords, by Gen. Milley and Gen. Odierno.

Gen. Milley then told the team he planned to read the entire 500,000-word study before its release and instructed the authors to broaden their research by interviewing former ranking officials such as former Defense Secretary Leon Panetta.

They did the interviews only to face another obstacle. Gen. Odierno had sidestepped the Army’s Center of Military History—the body is charged with publishing the Army’s official accounts of conflicts—because it had a reputation for taking years to prepare histories. In 2012, Gen. Lloyd Austin, the Army’s vice chief of staff, had asked Richard Stewart, then the center’s director, if he could put together an Iraq-war history in two years only to be told it would take five to 10, says Mr. Stewart.

The team planned to draw on the military-history center for help with copy-editing, maps and final publication. Despite Mr. Stewart’s earlier response, some at the center believed it should be playing a central role.

In November 2016, one of its historians, Shane Story, wrote a memo questioning whether the Iraq study was intended to “validate the surge” and thus burnish Gen. Odierno’s and Gen. Petraeus’s legacy. Mr. Story wrote that it didn’t follow the center’s time-honored practice of relying primarily on official documents, suggested it needed major revisions and proposed that Gen. Milley make the center a major partner.

Mr. Story’s challenge was put to rest. He says he wasn’t aware of Mr. Rayburn’s rebuttal to Army officials and declines to comment further.

In a bid to expedite publication, Maj. Gen. William Rapp, then commandant of the Army War College in Carlisle, Pa., says he argued his institution should publish the study instead of the history center.

As the service’s premier institution for teaching officers about strategy, the war college had a long tradition of publishing contrasting views under the banner of academic freedom. Issuing the study under the auspices of the war college, he reasoned, would distance Gen. Milley from some of its controversial conclusions.

‘Gold standard’

That didn’t help much. In an email to senior Army officials, Maj. Gen. Rapp said Gen. Milley had expressed concern during a May 2017 visit to the war college that the study might be “un-balanced” and stated that Gen. Milley would be “the release authority” to determine if it should be published.

Gen. Milley says he initially wanted to be sure the study was “not any kind of hero worship for any special group of individuals” and wanted a panel of outside reviewers to assess its quality and impartiality—an idea that Maj. Gen. Rapp and the study team supported.

Maj. Gen. Rapp says he thought the history was suitable for publication before he left the post in July 2017. “When I read it in the Spring of 2017, I was satisfied,” says Maj. Gen. Rapp, who is retired from the military and lectures at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. “It was not going to make everybody happy.

But if a history of the Iraq war was written that said the U.S. Army was perfect, that this thing went down exactly as we wanted it to, and there is nothing to learn from it, it would not be worth the paper it is printed on.”

When the study was shifted to the war college, plans for a foreword by the Army leadership were dropped in favor of one by the war-college commandant. In May 2018, war-college officials believed they were near the goal of publishing the first volume the next month.

After Army public-affairs officials brought the coming release of the study to the attention of Army leaders, the service put it on hold. Army officials began to comb through the text so that more than two dozen military leaders, including Defense Secretary Jim Mattis, who held several military commands during the Iraq war, could be informed about what the study said about them.

Seems to me that the time between now and Labor Day weekend is the perfect time to release,” he wrote. “We will keep as an academic release.”

Labor Day came and went. Maj. Gen. Kem also sent a marked-up copy of the history’s final chapter to the authors, asserting some of their conclusions were “too preachy” and reflected “too much hind-sight bias.”

He challenged the team’s conclusion that commanders in Iraq never had enough troops. “Has any commander in history had all the troops they wanted?” he wrote. He took exception to the conclusion that the Army may have penalized officers whose innovations conflicted with superiors’ faltering strategies.

Maj. Gen. Kem says he wasn’t trying to censor the account but wanted the team to focus its conclusions more on military operations instead of policy. The team wasn’t required to make his suggested changes—and the authors didn’t.

The senior Army officials also thought the study should be cast as an independent “work of the authors,” the note indicated, instead of being described as a project by the Chief of Staff of the Army’s Operation Iraqi Freedom Study Group.

Brig. Gen. Jones said earlier this month that eliminating the foreword was appropriate because an official decision to include one had never been made and forewords are typically included only in official book-length Army publications. Mr. Esper declined to be interviewed.

Last week, Gen. Milley intervened, reviving the original plan to include forewords by himself and by Gen. Odierno, which will run with one by Maj. Gen. Kem.

Gen. Milley says the authors will be again identified as members of the Army chief’s study group. While the study isn’t an “all encompassing” history, he says, he considers it “a solid work” and hopes it is issued by Christmas.

Source

RSS Feed

RSS Feed