Previously, the only way to pass intelligence at Bagram between the U.S. and partner nations was to hand it over as hard copy. These two first nodes in what would eventually become a larger network, known as CENTER ICE, would end the paper shuffling, ultimately saving the lives of troops in combat.

The NSA was to set up one of the two initial systems at Bagram for its own use, and the other for its counterpart from Norway, the Norwegian Intelligence Service, or NIS. The Norwegians were perfect guinea pigs. A “gregarious, friendly bunch” who threw good barbecue parties, they had “almost no collection capability” to eavesdrop independently and were thus “heavily dependent on the U.S.,” an NSA staffer at Bagram later wrote on an internal agency news site, SIDtoday. (The article and the other intelligence documents in this story were provided by NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden.) One of the new terminals failed when the NSA attempted to turn it on, but after the provision of some “necessary spares,” both were operational.

Spies from the two nations were about to get a dramatic example of how powerful the digitization of intelligence-sharing could be. One morning a few weeks after CENTER ICE went live, the Norwegians sent an urgent email using the new system: “Our guys think they are being shadowed… Are you seeing anything?”

“This initial success was exactly what we hoped would happen as a CENTER ICE proof of concept,” wrote the NSA staffer.

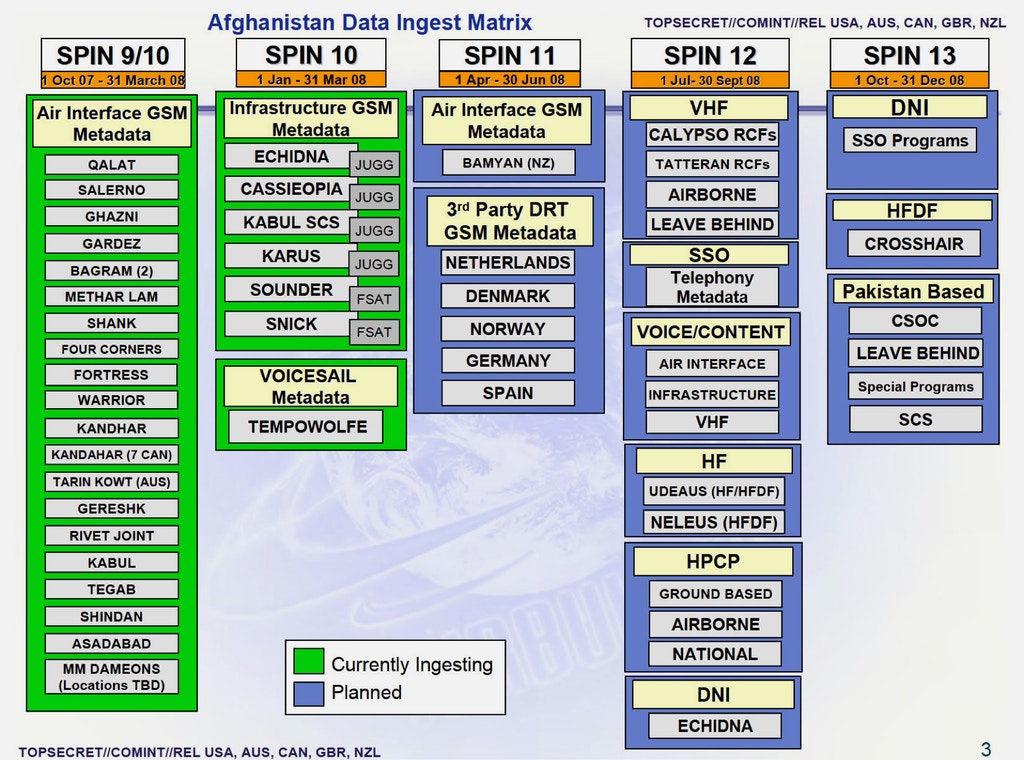

CENTER ICE was just the beginning, a step toward a much more aggressive experiment in the same vein. Norway would soon be among the first coalition partners to share, in real time, a wide range of data on Afghanistan, including essentially raw information scooped up from cellphones and fed into a revolutionary new local processing system called the Real Time Regional Gateway, or RT-RG. In 2011, according to documents published with this story, intelligence drawn from RT-RG was involved in more than 70 percent of all combat operations in Afghanistan, including 6,534 “enemies killed in action.”

There has been some public scrutiny of how the United States relied heavily on signals intelligence for those killings, which often resulted in civilian casualties.

But the fact that Norway and some of the U.S.’s closest allies helped feed this system with their own spy work has not been reported before. This is partly because documents linked to Norway’s participation in RT-RG, when examined in 2013, were misunderstood by various journalists, including two co-founders of The Intercept, as indicating that the NSA was engaged in mass spying on the citizens of allied countries, including Germany, France, Spain, Norway, and Italy.

A set of documents from the Snowden archive about RT-RG, reviewed by The Intercept in partnership with the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation, or NRK, sheds new light on how Norway came to depend on real-time intelligence-sharing to save Norwegian lives, while at the same time contributing to targeted killings and captures with no oversight or control over how data it had collected was used.

The revelations raise questions about the complicity of the U.S.’s other European partners in such controversial targeting practices and underline how RT-RG blurred the lines between sources of intelligence, corroding the ability of partners to impose special rules on how their data was handled — a particularly salient issue now that the system is in use by U.S. law enforcement entities.

Norwegian Defense Minister Frank Bakke-Jensen told NRK that Norway is not responsible if intelligence it shared was used by other nations — such as the U.S. — to kill innocent civilians. “We have no control over how another nation uses this information, but we require that they operate within International Law,” the defense minister said. He added that Norway does not review how data shared by the Norwegian intelligence service is used.

“There is no doubt that Norway was a full-fledged participant in this cooperation,” Kristian Berg Harpviken, a leading Afghanistan expert from the Peace Research Institute Oslo, told NRK. “We bought the whole package, so we must take responsibility for the totality of the war.”

The documents also show how RT-RG, within less than five years, migrated from the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan to the U.S.-Mexico border, where it was used to combat drug trafficking and people smuggling — a vastly different type of mission.

“The news that the NSA transported a mass spying program designed for war zones in Iraq and Afghanistan to the U.S.-Mexico border is both alarming and totally unsurprising,” said Elizabeth Goitein, co-director of the Liberty and National Security Program at the Brennan Center for Justice. “Mass surveillance is always initially justified as a necessary defense against foreign enemies. Then comes the inevitable mission creep, as surveillance methods originally conceived as tools of war or foreign espionage are brought home and turned inward.”

The Whole HaystackThe first Real Time Regional Gateway was deployed to Baghdad in early 2007. The timing was no coincidence. Four years in, Operation Iraqi Freedom, the U.S.-led military invasion of Iraq, had descended into sectarian violence and anti-coalition attacks, resulting in an all-time high number of casualties.

In spite of a massive surge of U.S. troops, the security situation was deteriorating, with roadside bombs and other improvised explosive devices increasingly common. In the Green Zone, Baghdad’s fortress-like international area, mortars and rockets rained down, requiring U.S. Embassy staffers to wear flak jackets and bulletproof helmets when walking between buildings, “worn out and tired of sitting in hallways,” as one SIDToday update put it.

This dire situation provided an opportunity for then-NSA Director Keith Alexander, who firmly believed that his agency could make the difference needed to win the war. His opening gambit was a system called RT10 — a “very high-priority initiative at NSA” at the time, according to Alexander’s science adviser, engineer James E. Heath. “The goal of RT10 is to get essential NSA cryptologic capabilities to the military front lines in a matter of seconds and minutes (‘real time’), not hours and days,” Heath wrote in SIDtoday.

The new system, Heath explained, would do away with the “latencies associated with transmitting and ingesting collection,” i.e. sending data acquired in Iraq back to NSA facilities in the U.S. By storing and processing the data locally, there would be less need to filter it, allowing for a wider net to be cast so that the NSA would have much more data available for retrospective analysis.

“Collection that would otherwise have been discarded because it could not be directly linked to a known target is now subjected to analytic algorithms that can reveal new targets of interest,” Heath wrote. In order to cover Baghdad, the RT10 system would need to be able to ingest 100 million “call events” or metadata records, 1 million “voice cuts” or recordings of phone calls, and another 100 million internet metadata records — per day.

At these volumes, RT10, the first iteration of what would become Real Time Regional Gateway, signaled a radical shift from traditional signals intelligence doctrine: from collecting and storing only what’s needed to find the “needle in the haystack” to Alexander’s “collect-it-all” philosophy, first described in a Washington Post article by a former intelligence official as “Let’s collect the whole haystack.”

According to a PowerPoint presentation authored by Heath, RT10 would result in “better decisions in less time.” Not only would it be able to geolocate targets almost immediately based on their cellphones, if offered “pattern-of-life” analysis, detecting when targets used multiple phones or otherwise “deviate in behavior.”

In one instance, RT-RG was put to task against a “particularly elusive” Iraqi target who was ”known to take his cell phone completely apart when he went home to prevent our tracking,” according to SIDtoday.

Unable to properly distill the target’s pattern of life, NSA analysts instead turned the powerful surveillance tool against his wife. She would travel to south Baghdad on weekends to be with her husband, thus revealing a likely future location at which he would be vulnerable. So the combat team “locked onto the wife’s cell phone selector for confirmation” and “raided the location identified by the RT-RG tools.”

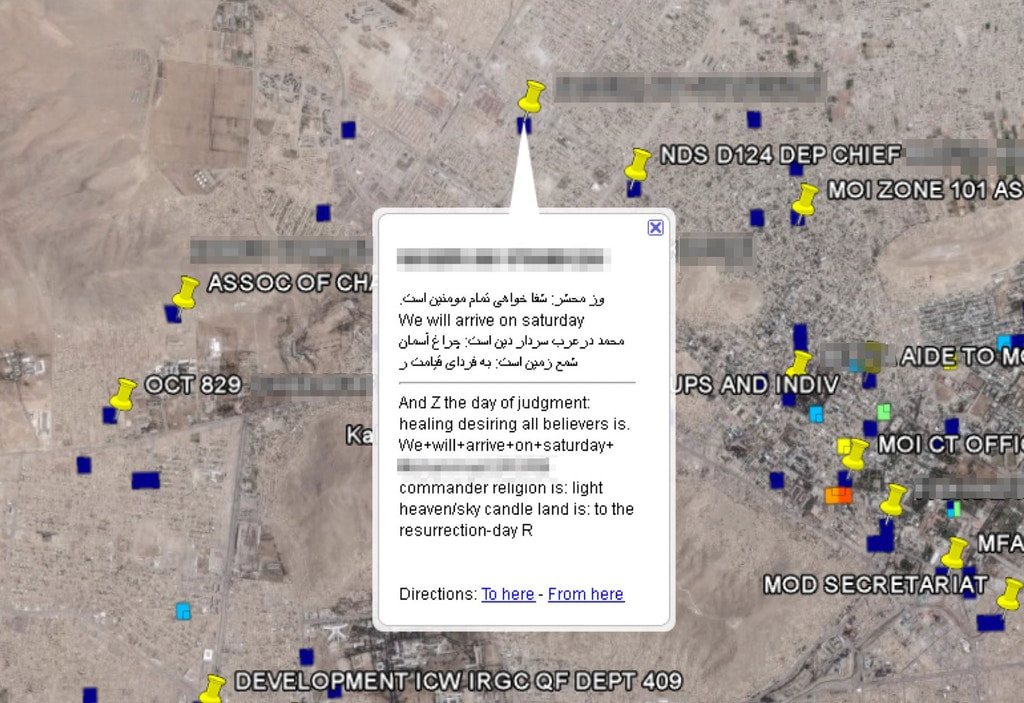

The Rockets Stopped FallingRT-RG soon attracted interest from outside the military and for military operations well outside Iraq. An NSA employee deployed to Baghdad in 2009 described, in SIDtoday, how he was asked to demonstrate the system to enthusiastic representatives from the FBI and other government agencies. The employee showed off a screen mapping live insurgent movements, with “Arabic text messages scrolling across the bottom as the insurgents sent messages” to one another.

I could see it was starting to sink in with many of the ops guys… An analyst from the FBI raised his hand and, pointing at the screen, asked, “Is this why the rockets stopped falling on the Green Zone?” — shaking his head in awe, he watched [as] one of his own targets moved across the screen, tracked in near real-time — to which I nodded and smiled.

By the time the Real Time Regional Gateway was churning away at the haystacks of data emerging from the Baghdad area, plans for a new RT-RG installation in Afghanistan were already in full swing.

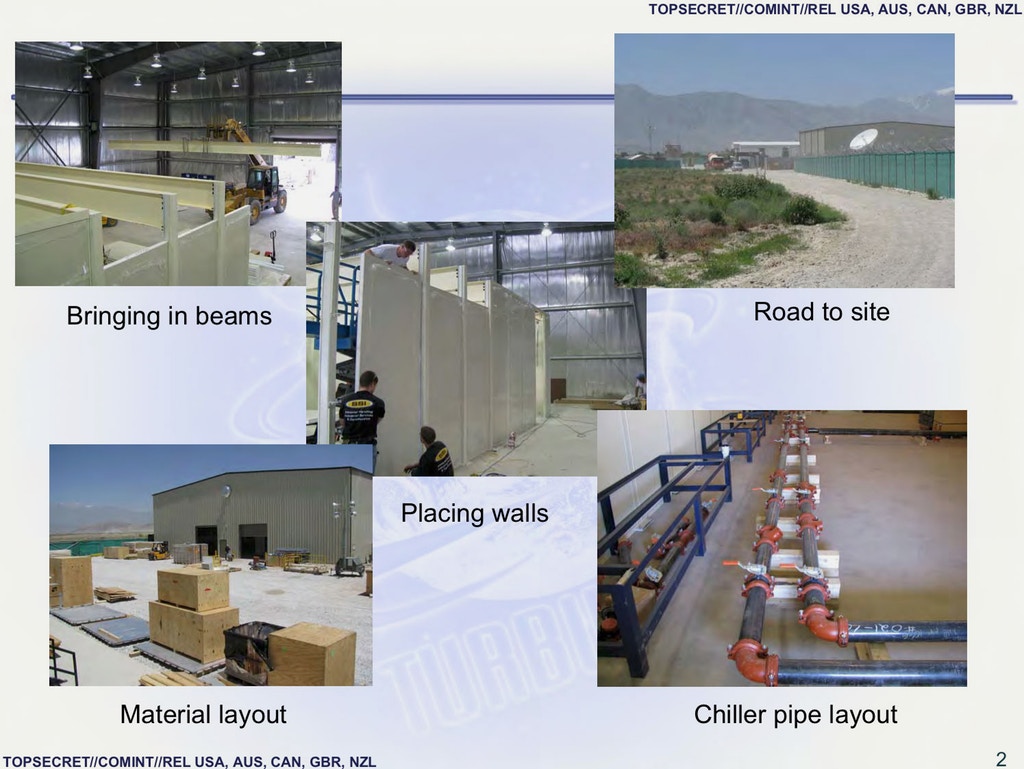

Back at Bagram, where CENTER ICE had made its debut, a new state-of-the-art data center was to be erected for RT-RG in a mine-strewn, far-off corner of the airfield called Area 82. Several documents in the Snowden archive reflect an unmistakable pride in bringing advanced cloud computing infrastructure to this desert plot in Afghanistan, a country where internet access was banned by the Taliban in 2001.

The new technology simulated the radio receivers operated by mobile phone companies, tricking cellphones into connecting and then intercepting their communications. It was employed by devices commonly referred to as Stingrays, after one early brand, and dirtboxes, after the manufacturer Digital Receiver Technology Inc., which Boeing bought in 2008.

Ahead of European allies’ deployment to Afghanistan, they would have purchased and received training from the NSA in “specific Digital Receiver Technology (DRT) capabilities” in order to “exploit the communications they are expected to encounter,” as arranged for Spanish forces in 2005 and described by SIDtoday.

The DRT collection units were part of a bigger plan: to feed the newly constructed data center in Bagram with intercepted mobile phone communications from areas in Afghanistan where the NSA previously had little or no coverage.

Photographs included in the data flow document show the RT-RG data center at Area 82 during the final stages of construction, with trucks bringing reinforced steel beams into a hangar and an advanced cooling system in place for the servers.

Voice-monitoring capabilities were provided by a system called ONEROOF, which held audio intercepts. Together, ONEROOF and RT-RG enhanced “the warfighter’s ability to ‘find, fix, and finish’ the adversary,” that is, to locate, kill, or capture a human target, an NSA liaison to the military’s Central Command told SIDtoday.

So-called target development procedures that would normally require an analyst on the other side of the globe to query different databases and use a number of tools to manually enrich the intelligence were automatically available in RT-RG, provided it had enough data.

For example, instead of an analyst manually querying phone metadata for specific events that would help determine the likely “bed down” location where a target would sleep, RT-RG would automatically pre-calculate such locations for all entered targets. It would automatically look for people traveling with a target. And it would visualize the results of these traditionally time-consuming tasks with color-coded overlays on satellite images, so that military commanders could make quicker, and supposedly better, decisions in the theater.

RT-RG did not just make U.S. forces more lethal; it changed how they fought. A longtime NSA analyst put it this way in SIDtoday: Unlike in Vietnam, where the enemy mainly used Morse code over the radio, today’s enemy “is mainly using the mobile phone to communicate.” New technology “has allowed us to exploit a mobile communication for its content (‘find’) (..) and pinpoint its location (‘fix’) within a very small radius,” requiring “only a platoon-sized force (if that) … to action (‘finish’) the target.” A platoon normally includes roughly one dozen to four dozen soldiers.

In the words of the then commander of U.S. and allied Afghanistan forces, Gen. David Petraeus, quoted in a presentation prepared for a conference of technical minds from the NSA and its closest allies, “RTRG is the most significant [signals intelligence] support to the war fighter in the last decade.” But while RT-RG would reduce the number of troops needed on the ground, it coincided with an increased number of NSA staffers and soldier-spies deployed to war zones. As former NSA Deputy Director Rick Ledgett stated publicly, the NSA “deployed 5,000 NSA people to Iraq, and 8,000 to Afghanistan – and in total 18,000 to hostile areas around the world.”

At the same time, reliance on signals intelligence, or “SIGINT,” increased dramatically in the battlefield.

“Over 80% of combat operations in Afghanistan are driven by SIGINT or have SIGINT contribution,” former NSA Afghanistan representative Brian Goodman told SIDtoday in 2009. ”That is an indisputable fact. … Not a single combat operation goes on without SIGINT coverage.”

Two years later, in 2011, RT-RG “played a key role in 90 percent of all SIGINT developed operations,” according to the conference presentation. This translated to 2,270 capture/kill operations, 6,534 “enemies killed in action,” and 1,117 detainees. In comparison, the U.S. recorded 415 casualties in Afghanistan in 2011, while the U.K. and other nations recorded a total 148, according to iCasualties.org. (The presentation did not qualify the terms “enemy” or “killed in action,” or mention whether operations based on intelligence from RT-RG lead to the death or capture of the wrong people.)

Quid Pro Quo Intelligence-Sharing

As RT-RG became increasingly central to waging war in Afghanistan, the U.S. encouraged allies to put more data into it, upping their complicity in what would later be exposed as a deeply flawed infrastructure for killing and capturing those flagged as enemies.

The U.S. side of this system for killing people, often on the basis of phone monitoring, has been documented. One Intercept report described how U.S. drone strikes would hit the wrong people because targets had begun swapping identifying SIM cards out of their phones, aware of their adversary’s ability to track handsets. Another report, part of the Drone Papers, detailed how, during a five-month campaign in northeastern Afghanistan, “nearly nine out of 10 people who died in airstrikes were not the Americans’ direct targets.” The Drone Papers also revealed how “military-aged males” killed in drone strikes would be labeled as enemies killed in action unless there was information indicating otherwise.

The participation of Norway, and other U.S. intelligence partners, in feeding this lethal system has not received the same level of popular attention.

Indeed, the main difference between the Iraq and Afghanistan implementations of the Real Time Regional Gateway was the introduction of extensive intelligence-sharing between coalition partners.

To manage this complex, multinational environment, the U.S. came up with what was essentially a tiered model, in which the closest partners enjoyed the best access to lifesaving intelligence in return for filling collection gaps and sharing scarce resources, such as linguists. This new approach, according to a SIDtoday announcement, was put in motion on the NSA’s initiative “to include greater reliance on our” signals intelligence partners in response to a “potential troop buildup in Afghanistan” and “expected new information needs.”

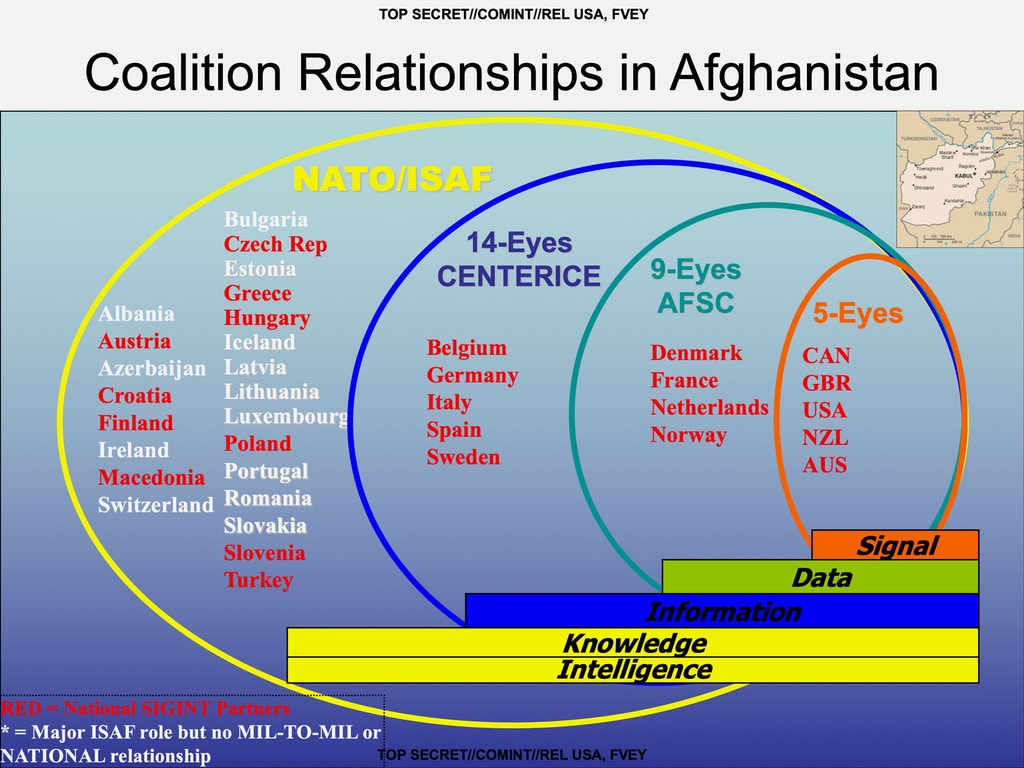

A June 2009 NSA briefing laid out the structure of the Afghanistan spying coalition.

At the second-highest tier was the newly formed group called the Afghanistan SIGINT Coalition or Nine Eyes, which added Norway, Denmark, France, and the Netherlands to the five.

Access to Nine Eyes required sharing the mobile phone surveillance collected using the newly acquired dirtboxes in real time or near real time. In return, members got access to data from RT-RG, “real-time threat warning,” “find-fix-focus collaboration and analysis,” and superior targeting and geolocation data, according to the June 2009 briefing.

The Nine Eyes nations, except for France, were ingesting data from their dirtboxes into RT-RG by mid-2009, according to an NSA presentation. (The reason for France’s absence could be that its military intelligence didn’t receive the necessary training before October 2008, when an NSA team traveled to Haguenau in Alsace, France, to give its counterpart from the 54e Regiment de Transmissions — the electronic warfare branch of the French army — a “crash course in exploiting metadata from GSM, CENTER ICE and RT-RG,” according to SIDtoday.)

At the next membership level — 14-Eyes — were Belgium, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Sweden, with access to the CENTER ICE communications and sharing platform, and some of the same benefits but with delays and limitations.

At the bottom, dubbed 41 Eyes, were the remaining countries participating in the International Security Assistance Force coalition in Afghanistan, or ISAF, getting the standard NATO intelligence fare.

In this quid pro quo structure, the most aggressive participants in the U.S.-designed surveillance regime would be rewarded with a constant flow of lifesaving intelligence on enemy movement and accurate targeting data. This is spelled out in a memo on the “NSA intelligence relationship with Norway,” which shows that the Norwegians provided signals intelligence “analysis as well as geolocational and communications metadata specific to Afghan targets of mutual interest” in return for “daily force protection support in Afghanistan and technical expertise to support target development of Afghan insurgent targets”.

The NSA “Could Be at Area 82 for 50 Years”

By late 2009, international Afghan surveillance-sharing through RT-RG was becoming entrenched and institutionalized. As it grew, problems surfaced.

In October, a new and “’Super Sized’ SIGINT Facility” opened at Area 82 in Bagram. The Afghanistan Regional Operations Cryptologic Center, or A-ROCC, was constructed in less than a year, offering facilities, housing, and even a fitness center for more than 250 people. All materials and equipment had to be transported from the U.S. via ship and “overland via the Khyber Pass” or flown “directly to Bagram Airfield on six Boeing 747s,” a member of the NSA Afghanistan-Pakistan management team wrote in SIDtoday.

French, British, and American spies were already “working side-by-side,” the manager wrote, with personnel from “Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Norway, Denmark, and possibly the Netherlands” soon to follow. The new facility, the article noted, was the result of “major policy decisions” and would allow “nine SIGINT coalition nations to work together as one.” It would also double the number of linguists available to process intercepted texts, phone calls, and other material: “Who could have imagined even a year ago that a French linguist, using U.S. collection sources, would be providing tactical support for operations being carried out by Polish forces on behalf of ISAF?”

The new facility allowed the inner circle Afghanistan SIGINT Coalition partners to plug into RT-RG “via several ‘peering points,’” an NSA liaison to Central Command told SIDtoday. Peering is a networking term for the exchange of traffic between networks, essentially the act of plugging one into another.

Connecting the partners to RT-RG posed a growing challenge in terms of different national, legal, and political environments. “With the increase in partnering,” the liaison, Col. Parker Schenecker, wrote, “sanitization and dissemination presents a growing challenge” — a reference to the need for intelligence to be filtered and “cleaned” before it can be shared, and for restrictions on its distribution to be observed. But, according to Schenecker, the NSA stepped up and showed a “willingness to take manageable risks to maximize effectiveness.”

In 2010, Sweden and Germany joined what had been the Nine Eyes coalition and by January 2013, according to a document previously publishedby Der Spiegel, Belgium, Italy, and Spain had joined the group, bringing the total number of nations participating in the Afghanistan SIGINT Coalition to 14. According to the same document, the Germans had become the “third largest contributor” to RT-RG.

At Area 82, it seems safe to say, the sort of extensive intelligence-sharing exemplified by RT-RG became a cornerstone of U.S. intelligence strategy. In his SIDtoday interview, Goodman, the former NSA Afghanistan representative, called Area 82 the “NSA’s foundation for the long term — we could be at Area 82 for 50 years if we needed to!”

Showdown in Oslo

The U.S. military was so gung-ho about RT-RG that it produced, judging from the Snowden archive, many documents about the system’s results. Some of this material, created using an NSA data management and visualization tool called BOUNDLESSINFORMANT, was misunderstood by journalists, including Intercept co-founders Glenn Greenwald and Laura Poitras, working with European news outlets during the early days of reporting on Snowden material. This led to a dramatic showdown.

On November 19, 2013 in Oslo, Norway, in the Ministry of Defense press room, chaos reigned, with reporters and photographers frantically trying to get ready. E-tjenesten, as the Norwegian Intelligence Service is known locally, rarely spoke to the press. This — a briefing with less than half an hour notice in response to a news story — was unprecedented.

Earlier that November morning, Norway’s second-largest paper, Dagbladet, had detonated the potentially biggest spy bombshell in decades. “Secret documents about Norway,” the front page of the tabloid said, next to the iconic image of Snowden: “The US spied on 33 MILLION Norwegian calls.”

The report was based on a graphic from BOUNDLESSINFORMANT. It showed a graph labeled “NORWAY Last 30 Days,” suggesting that the NSA hoovered up information about ordinary Norwegian citizens’ phone calls. “Even a child’s phone could have been tapped,” the paper stated.

The story completely dominated the morning news cycle. “Friends should not spy on each other,” Prime Minister Erna Solberg told reporters shortly before 10 a.m.

In the Ministry of Defense press room, at 11:15 a.m., head of E-tjenesten Kjell Grandhagen entered the room, making a rare public appearance in full uniform. The day before, he had tried to convince Dagbladet not to publish the story.

“Today, Dagbladet printed several articles alleging that the U.S. intelligence organization NSA collected traffic data on 33 million telephone calls in Norway,” he read, looking up from behind his reading glasses. “This is not correct.”

The document, Grandhagen said, was not about NSA spying in Norway. Instead it reflected data that his service had collected abroad in support of Norwegian military operations and “related to international terrorism, also abroad.” The data had been shared with multiple foreign partners, including the NSA. This was perfectly legal and had been reported to the Norwegian Parliamentary Intelligence Oversight Committee as per standard procedure.

“We know the content of this and perfectly recognize the traffic pattern presented by Dagbladet. We are the ones who collected it,” Grandhagen told a reporter from Dagbladet during the ensuing Q&A. “We are 100 percent sure that our explanation is correct.”

The counterattack worked. In a follow-up statement, Solberg, retreating from her earlier proclamation that that “friends should not spy on each other,” now dismissed Dagbladet’s allegations as “wrong.” The 33 million call events, she said, adding a new piece to the puzzle, had been recorded in Afghanistan, not in Norway. By the end of the day, Dagbladet’s news editor said his colleagues might have “misunderstood parts of the document.”

Norway was not the only country where military officials complained about reporting that stemmed from RT-RG. On October 29, 2013, after diplomatic tensions in both Spain and France following publications in El Mundo and Le Monde, Alexander, the NSA director, told the U.S. Congress that allegations in those newspapers were “completely false.”

“This is not information that we collected on European citizens,” Alexander said. “It represents information that we and our NATO allies have collected in defense of our countries and in support of military operations.”

It is now clear that the call events reported by Dagbladet were indeed collected by the Norwegian Intelligence Service and shared with the NSA during a 30-day period between December 2012 to January 2013. Greenwald and the other journalists interpreted them incorrectly in part because contextual information available elsewhere in the Snowden archive was not understood at the time or even available to the European publications.

Such information would have explained why documents used as evidence that the NSA conduced mass surveillance on cellphones in Spain, France, Norway, and Italy all indicated that “DRTBOX” was the primary collection method: The countries partnered with the NSA to buy dirtboxes for use in Afghanistan (and, in some cases, elsewhere), and shared the cellphone data they then collected. Denmark, France, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and Norway, all members of the Afghanistan SIGINT Coalition, shared a total of 258,703,534 metadata records collected using dirtboxes with the NSA between December 10, 2012 and January 8, 2013, according to the documents.

The Intercept has conducted a thorough examination of all the BOUNDLESSINFORMANT documents used in the disputed 2013 articles by European outlets. At the heart of the misunderstanding was how journalists interpreted two documents published with the first article about BOUNDLESSINFORMANT, co-authored by Greenwald and Ewen MacAskill for The Guardian newspaper and published on June 8, 2013.

The first document was an NSA presentation on how BOUNDLESSINFORMANT worked, the second an NSA set of Frequently Asked Questions about the tool. The first document said the tool could be used to determine “what assets collect against a specific country” — as well as “how many records are collected for an organizational unit … or country” (emphases added). The second document similarly stated that BOUNDLESSINFORMANT could show “how many records (and what type) are collected against a particular country” or “how many records are collected for an organizational unit (e.g. FORNSAT).” Journalists focused on the statements about collection against countries while disregarding the statement about collection for countries.

On July 1 2013, journalists from German newsweekly Der Spiegel, in collaboration with filmmaker Laura Poitras, published a cover story that drew on new BOUNDLESSINFORMANT documents purporting to represent collection against Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain. In reality, the documents reflected records shared with the NSA by foreign partners, including the BND in Germany.

A week later, Spiegel and Poitras, who stepped down from The Intercept in 2016, reported corrective information from the BND, which told the magazine that it was responsible for intelligence collection in Germany that had been attributed to the NSA; BND sources even identified for Spiegel a specific listening station in south Germany where some of the data originated — and said the rest came from German “telecommunications surveillance in Afghanistan.”

Journalists from Le Monde and El Mundo in Spain, working with Greenwald, went on to report on BOUNDLESSINFORMANT documents on France and Spain as evidence of mass surveillance by the NSA against these countries. Responding to denials from Grandhagen and others, Greenwald reiterated this interpretation in a piece in Dagbladet.

Greenwald, referring to this period in 2013, said, “At the time, Der Spiegel had already reported this interpretation, the NSA wouldn’t answer our questions, and they wouldn’t give us any additional information. I am totally in favor of correcting the record if the reporting was inaccurate.”

“The NSA documents themselves, in repeated places, stated that they purported to show how much data the NSA was collecting against each country,” he added. Further, when he and other journalists asked intelligence agencies to disprove their coverage, “those agencies repeatedly refused to provide any documentary proof that the NSA had erroneously characterized its own spreadsheets.”

“As a result, we noted the agencies’ objections to our stories, while also noting they were in conflict with the NSA’s own documents, but their refusal to provide any documentation made it impossible to conclude that the NSA’s own descriptions were false,” he continued. “It now appears that subsequent reporting has revealed that the NSA’s description was erroneous, and that these slides showed how much communication data was being collected by those countries in Afghanistan, rather than collected about those countries by the NSA.”

Spiegel issued a statement that read, “DER SPIEGEL has set the record straight six years ago. As soon as German Foreign Intelligence (BND) answered our reporters’ questions on the ‘Boundless Informant’ slides and their context back in the summer of 2013, we reported their version. BND’s detailed explanations and Keith Alexanders remarks before Congress have subsequently also been covered in the SPIEGEL-Book ‘Der NSA-Komplex.'”

Dagbladet News Editor Frode Hansen said the newspaper assumes that what Kjell Grandhagen said at the press conference in 2013 was correct. “His information corrects what we brought to the fore, that it is about monitoring telephone calls made in Norway,” Hansen said. “It appears that there’s massive surveillance abroad, but that this monitoring stops at the Norwegian borders. We published several articles associated with the documents, the same day we published the first article, and in the following weeks, we had several stories related to the documents.”

Faster Intelligence, at a Great Price

At the November 19, 2013, press conference, Grandhagen told a reporter from Aftenposten, the country’s largest newspaper, that Norway had been carrying out this type of collection for years, and would continue to do so. Asked whether “we are talking hundreds of millions of phone calls,” he said, “That may well be.”

It was not just Norway that collected and shared metadata with the NSA. The BOUNDLESSINFORMANT documents show that Denmark, France, Italy, Poland, Spain, and Sweden shared data collected using dirtboxes with the NSA by 2013. Germany and the Netherlands, both Afghanistan SIGINT coalition members, also shared cellphone metadata by 2013 and used DRTs in Afghanistan in 2009, the documents show.

There is no evidence to suggest that the data shared into RT-RG and used by coalition partners was subjected to any special limits or were exempt from find-find-finish and capture/kill operations.

Harpviken, from the the Peace Research Institute Oslo, was unaware until now of Norway’s role in the Afghanistan intelligence-sharing coalition and the RT-RG program. But he saw what happened in practice.

“Many called it an industrialization of warfare. We used special forces operations — especially night raids — on a huge scale, to either kill or capture Taliban commanders,” he told NRK. “We got the intelligence much faster. But it had great consequences for the civilian population. … Many civilian lives were lost due to imprecise intelligence. The rapid turnaround made it harder to insure the quality of the intelligence, and the large number of operations meant that civilian injuries increased accordingly.”

In 2010, U.S. Special Forces killed a number of people in a convoy that belonged to a candidate in the Afghan parliamentary election. It later turned out that the U.S. military had targeted the SIM card of a person believed to be a senior Taliban leader, when in fact the card belonged to a completely innocent person who contributed to the election campaign of a relative.

The incident was “illustrative of what can go wrong when your intelligence is bad,” said Kate Clark, a former BBC Afghanistan correspondent. She investigated the attack as a researcher for the independent think tank Afghanistan Analysts Network, interviewing survivors, witnesses, and Afghan officials, and speaking to senior officers in the special forces unit that executed the attack.

According to Clark, the investigation revealed “parallel worlds” between signals intelligence and the Afghan reality on the ground. “They were blind to human intelligence. Had they had any understanding of HUMINT, they would have discovered that [the relative of the parliamentary candidate] was well-known,” and not Taliban, she said.

There is at least one official acknowledgment that Norway was potentially complicit in such abuses. The Godal Committee, tasked with investigating Norway’s engagement in Afghanistan, said in its final report that Norwegian forces frequently acted based on statistics and technical analysis and had no control over how intelligence it shared was used by allies.

But the Norwegian military remains defensive.

“Good intelligence and good intelligence cooperation with allied countries result in lower risk of loss of military lives. We also reduce the risk of loss of civilian lives in this type of operation,” Norwegian Defense Minister Frank Bakke-Jensen told NRK.

According to a general statement by the director of the Norwegian Intelligence Service, Morten Haga Lunde, provided to NRK and The Intercept, sharing data “within an established intelligence partnership” is “neither in violation of international law nor Norwegian law,” and it is “legally unproblematic for such operations to include the use of drones or other legal weapons platforms, as long as the operations are conducted within the framework of the law of war and international law.”

RT-RG on the Mexican Border

In the spring of 2017, the NSA took RT-RG public and began hinting at other deployments of the system.

On May 7, the National Cryptologic Museum, a small, public-facing corner of the NSA campus in Fort Meade, Maryland, added a new display to its collection. Carefully avoiding any mention of cellphones or metadata, it explained how RT-RG represented a completely new way to combat the threats from improvised explosive devices and “Al Qaeda’s bomb making capabilities,” and how the program had been “extended from Iraq to Afghanistan and other conflict zones around the world” (emphasis added).

Days later, in a Fox News exclusive, Richard Ledgett, the NSA deputy director, spoke about the program in a rare public interview. In the segment, Ledgett explained how RT-RG “might connect something like a phone number to a location … and then display that to an analyst,” who would in turn warn a troop convoy about an impending ambush.

The two-minute segment, “Inside the government’s secret NSA program to target terrorists,” mentioned in passing that since it was fielded in Iraq and Afghanistan, the system had been used in “other conflict zones which the NSA will not publicly identify.” The Fox segment also didn’t mention whether these “other conflict zones” were linked to terrorism or interventions involving the U.S. military.

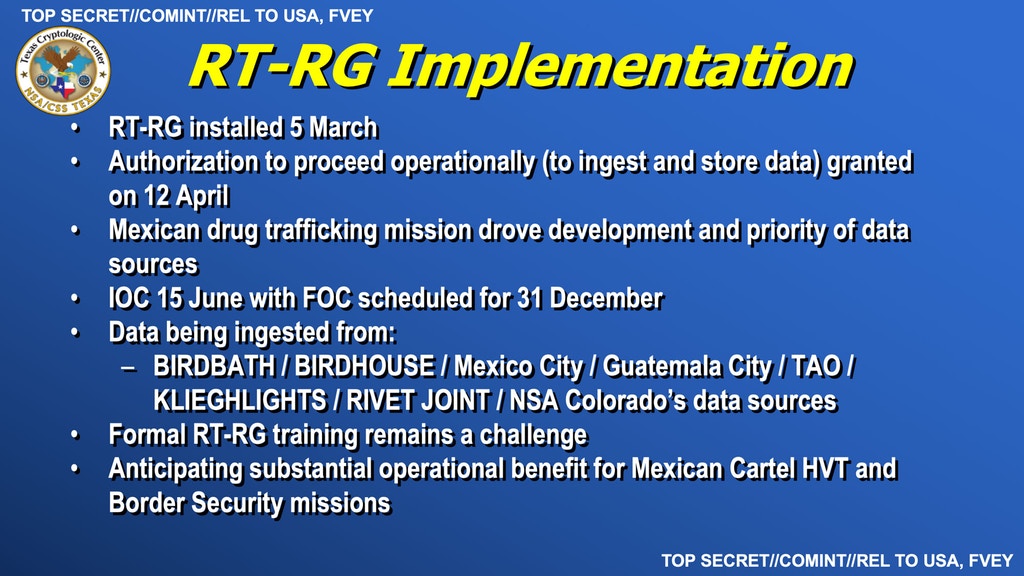

The Intercept can now reveal that one of the “conflict zones” in which the powerful Real Time Regional Gateway was deployed was the U.S.-Mexico border, where the system became operational in 2010.

In one week, the NSA document boasted, RT-RG was used “afloat on [a] subsurface platform[,] USS Georgia,” where it was able to receive “31 million GSM [mobile phone] events, leading to 10 high-value target voice ID and 90 tactical tip-offs.”

But perhaps the most controversial application of Alexander’s new tool dates back to February 2008, when a meeting was convened at the El Paso Intelligence Center, or EPIC, a Drug Enforcement Administration-led facility established in Texas to help secure the southern border and encourage information-sharing between federal agencies. An NSA memo summarizing the meeting shows that, the same month that Norway started using dirtboxes near Kabul, and several months before RT-RG in Afghanistan was declared operational, discussions were held about using RT-RG on the U.S.-Mexico border.

At the meeting were officials from the DEA, the anti-drug trafficking Joint Interagency Task Force South, the NSA, and EPIC, including a representative from U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Discussions with the Department of Homeland Security about sponsoring NSA network connectivity at EPIC are also referenced in the memo. At the meeting, the NSA was represented by Col. Barb Trent, deputy to Heath, the science adviser to the NSA’s director and an early RT-RG proponent.

According to the memo, the DEA was “very enthusiastic about and anxious to move ahead smartly on the acquisition of an RT-RG capability located at EPIC” and had requested “up to $10 Million for RT-RG” in El Paso. Another official present at the meeting was of “the opinion that the ‘funding will shake loose,’ because intelligence leadership was “in accord about the ‘value of sharing interagency data.’”

EPIC has “a particular emphasis on … illegal drugs, weapons trafficking, terrorism, human trafficking, human smuggling, illegal migration, money laundering and bulk cash smuggling,” according to the center’s website. No fewer than 21 federal agencies have staffers at the center, including the NSA.

Bringing RT-RG to EPIC was tricky because many law enforcement “customers” did not hold sufficient security clearances, the memo said. The solution, Trent said, was for the RT-RG tool to present the underlying data according to the clearance level of the user and that “these same issues were being worked in the RT-RG deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan.”

Another challenge was to ensure that the role of the NSA system was obscured if necessary when investigations arising from its use ever ended up in court. The NSA memo addressed this issue cryptically, saying that the “RT-RG capability in whatever form it exists at EPIC would have to respect and incorporate Special Operations Division’s (SOD’s) role.” The SOD is a controversial DEA division that uses NSA intelligence to create leads for federal and local police, but since the source can’t be known, the division trains agents to use so-called parallel construction to cover up where the information originated, as reported by The Intercept.

The ultimate goal, the memo stated, was “linkage between the law enforcement and SIGINT worlds” — that is, between the NSA and law enforcement entities like the DEA. But there were “multiple policy issues to be addressed before that can be realized.”

One thing that was unclear in 2008 was whether EPIC would get its own RT-RG or use the one at NSA Texas.

It is, however, clear that the latter facility, located in San Antonio and focused on intelligence needs to the south of the U.S., used RT-RG starting in June 2010 to help stanch the flow of migrants and drugs into the U.S. Six staffers from NSA Texas People Smuggling Organization branch had received RT-RG training, according to an NSA document dated August 12, 2010. The cellphone of one alleged such person, “SIA [Special Interest Alien] smuggler Chuy in Reynosa,” was targeted “for geolocational purposes,” the document said.

The document stated that getting “formal RT-RG training” was a challenge and that only 13 of 28 NSA Texas Southern Arc Target Development staffers had received it.

The main targets tracked by RT-RG at NSA Texas, the document made clear, would belong to Mexican drug cartels, and RT-RG was expected to bring ”substantial operational benefit for Mexican Cartel HVT [high-value targets] and Border Security missions.”

RT-RG brought to the border region a tactic used in Iraq: pattern-of-life analysis, in which a target’s future movements are anticipated by mapping their past activities and those of their associates. In Iraq, the NSA had hunted down an elusive insurgent, who frequently disassembled his phone, by targeting his wife’s phone, thus homing in on the couple’s jaunts to south Baghdad. In or around Mexico, it used similar types of analysis against three “hit squad” members of the Vicente Carrillo Fuentes Organization, a cartel based in Ciudad Juárez across the border from El Paso. This pattern-of-life work led to the capture of two of the cartel members, with “an imminent operation pending to capture the third,” according to the August 2010 document.

The data was laundered by “obfuscating the source information and filtering out metadata from countries of no interest to that area of responsibility” and would “provide RT-RG Texas with 85% of their input volume, which contains 60% of the hits on their targets,” another report said.

Beyond the backbone data, RT-RG at NSA Texas in 2012 also added data obtained from AT&T’s network under a program known as FAIRVIEW. It is not clear how data was processed for use at NSA Texas, but one document mentions a filter system called SHELLTRUMPET that handled the mass surveillance data flowing into San Antonio.

To the NSA, the deployment was a success story, according to a geospatial analyst at NSA Texas, writing in SIDtoday. To take surveillance strategies developed to minimize U.S. casualties in battle and use them for law enforcement was, the analyst wrote, the “perfect example of taking techniques developed in one environment and applying them in other targeting situations.”

To the rest of us, such transplantation of spycraft, whether among federal agencies at the U.S. border or among various countries in Afghanistan, might serve instead as an example of the dangerous path that technological innovations can take as they slowly — but surely — “creep” from one context to another.

“Foreigners also have privacy rights under international law, including treaties the U.S. has signed. The Snowden documents make clear that these rights were systematically violated,” said Goitein, the national security specialist from Brennan Center.

“Although government officials have claimed that the RT-RG program was highly effective, such claims are always based on classified evidence and must be taken with a grain of salt. The last time such a claim was rigorously investigated — when officials claimed in 2013 that “bulk collection” of Americans’ phone records was a valuable counterterrorism tool — it quickly fell apart.”

The NSA declined comment for this story.

Source

RSS Feed

RSS Feed