They, like the Brits, arrived to Iraq claiming to be 'liberators not conquerers'. The nationalist essence of both the revolt and resistance against coalition forces has been muted in recent years by sectarian inspired interpretations of Iraq's history - which this paper challenges.

The air of suspicion and distrust that loomed during the British mandate lingers on til today in a country whose history has been undoubtedly shaped by the insatiable appetite of external powers for oil and hegemony. While important differences distinguish the time of the British in Iraq from the Americans in 2003, a closer look reveals unlearned lessons and repeated mistakes by powers whose attempts to forcibly govern its people have failed.

Baghdad’s fall in March the following year signalled Britain’s first significant feat, but would soon be dampened by reluctance on their own part to deliver on the promise of Iraqi self-governance. Britain’s double dealing and attempts to captivate Arab hearts and minds held only limited sway. In cherry picking Sherif Hussein Bin Ali (Hijazi) to lead the Arab revolt, Britain worked to advance its interests by exploiting Arab discontent with Ottoman rule. Despite that, there was an unwavering acceptance of British forces as occupiers on Iraqi turf. As the Ottoman dynasty crumbled, a new vacuum emerged that came to be filled with a new conception of ‘Iraqi-ness’, but not one divorced from religion.

The commingling entities, nationalism and Islam, were central to the formation of a newly conceived identity, to which everyone could subscribe. This was one of the marking features of the 1919/20 uprising and the actions which made this possible. Although recent years have witnessed an alarming surge in sectarian-inspired frames of analysis applied to such an event, it would be incredulous to claim that sect X, Y or Z led the revolt, in the face of existing facts. Nationalism grew as a guiding yet burgeoning force, based not simply upon anti-colonialist sentiments. It was solidified beneath the shared desire for self-determination between Iraqis of all political and religious stripes.

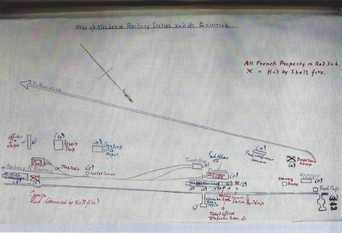

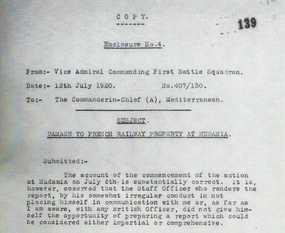

| As protests mushroomed in Baghdad, Najaf, Karbala, Tel Afar, and elsewhere, they were read by the occupying force as localised events. Yet they were not unconnected from what was happening regionally, especially in neighboring Syria under French control. What the British viewed as a spell of tribal mischief that would gradually melt away actually snowballed into a common, cross-sectarian, insurgency, clothed in the language of nationalism and promoting an all-encompassing identity. Religious sects, described today as irreconcilably divided, ungrudgingly joined forces to coordinate industrial action, as had been proposed by Saleh Al-Hilli. There was also reciprocal engagement and observance when it came to religious ceremonies and festivities. Ashoura and Mawlid Al Nabi (prophet Mohammad’s birthday) were merged to mobilise Iraqis, regardless of religious differences. Mosques offered these communities spaces where they could mobilise politically. Nationalists, as Gertrude Bell wrote, “picked up their tempo in continual meetings at the mosques. Extremists are calling for independence and refuse moderation and these have dominated the mob in the name of Islamic unity and the rights of the Arabs”. Notwithstanding these joint efforts, recent scholarship remains guilty of privileging certain interpretations that valorise the struggle of one sect over another, serving to trivialise the nationalist character of the revolt. The accepted narrative holds that cross-religious mobilisation as either (a) ‘unprecedented’ or (b) presumes that mutual aversions are shared between religious sects. In his critique of these narratives, Usama Makdisi argues that these claims perpetuate an ‘orientalist paradigm’, which judges rather than analyses sectarian outlooks and practices. |

| In light of the rich trove of accounts about the ‘Great Iraqi Revolt’ much disagreement is expected, such as on the question of where the revolt began. The village of Abu S’khair in the mid-Euphrates (and not the capital) is cited as one of several starting points. The triggering point is said to have been the ill-treatment of Sayyid Alwan Al-Yasri by a British Army captain, as they argued over Iraq’s independence. Yasri’s response was to rally indigenous masses in revolt of a system whose insensitivity could no longer be endured with patience. In Najaf, Ayatollah Taqi Al Shirzai also sounded calls for non-violent resistance, out of fear of suffering heavy casualties, but without obstructing those who chose the path of rebellion. |

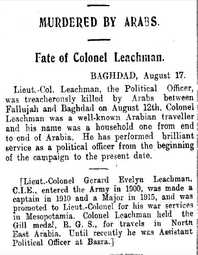

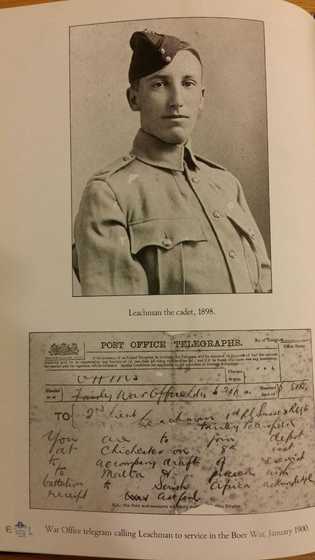

| Misinformation also surrounds another famous incident of resistance at Khan Nuqta, a police post, east of Abu Ghraib and on the road towards Baghdad. On 12 August 1920, the head of the Zauba tribe, Sheikh Al Dhari, murdered one of Britain's most valued colonial officers, Gerard Evelyn Leachman, known for his exploits in the Arabian desert. Dhari had become increasingly dissatisfied with the way a foreign occupier was exercising brute force in his country. Leachman, unhappy with the Zauba tribe’s position on British governance, decided to pay Dhari a visit. The details of their conversation are unknown till this day, but the altercation led to Leachman being shot then stabbed to death by the chief of Zauba. Rumour has it that Dhari's son Khamis, was responsible for the shooting, but the story, as told by Sheikh Hatem Al Dhari (the sheikhs nephew) counters such claims. Khamis, as Hatem recounts, was out conducting raids against local bandit gangs, “Leechman was in fact shot by his younger son, Sulaiman”. |

Times of India 21 Aug 1920

Times of India 21 Aug 1920 | An overlooked incident during the first battle of Fallujah in 2003 provides one case in point. As American forces battled against organised insurgent groups for control of the city, reinforcements were sent from an unexpected ally, Moqtada Al Sadr. Officers drawn from Jaysh Al Mehdi were sent to bolster resistance efforts against a common enemy. At the time of the battle of Najaf, The Association of Islamic Scholars in Iraq (AMSI) received a surprise visit from a Jaysh Al Mehdi representative, Qais Al Khazali. He appealed to AMSI to rally newly formed Sunni resistance factions to provide Khazali with military backup. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed