Appreciating the dependence on Iran for the provision of electricity means delving into the extraordinary mess that is Iraq’s power grid, consisting of the power plants that generate electricity; transmission system that transport this electricity to population centres; and distribution networks which then distribute this electricity to end users. Decades of conflict have damaged most parts of the grid and, coupled with poor maintenance of the parts that escaped damage, this has rendered the grid impotent. Rebuilding the grid post-2003 was hampered by the rolling dysfunction of successive governments, in which significant capital expenditures were neutralised by mismanagement, lack of coordination between ministries, and the county’s corrosive corruption. The public’s frustration over this impotence extends beyond the inadequate provisioning of electricity throughout the year, as the summer’s intense heat creates a particularly acute need for electricity, exposing the grid’s shortcomings.

These start at the generating stage with the gap between nameplate capacity, i.e. the maximum sustainable power output under ideal conditions, and actual output. While a gap always exists between these two, in 2018 the nameplate capacity was 30.3 gigawatts (GW), while effective capacity through the year was a mere 11.9 GW. A primary reason for this gap is the lack of appropriate fuel supply, in this case gas, which leads to substitutions by fuels such as crude or heavy fuel oil with the result that plants run at less than 60% of capacity – in 2018 only 62% of operating gas-powered plants actually used gas. Other reasons include poor maintenance and lack of cooling in high ambient heat. Moreover, up to 20% nameplate capacity in 2018 was non-operational.

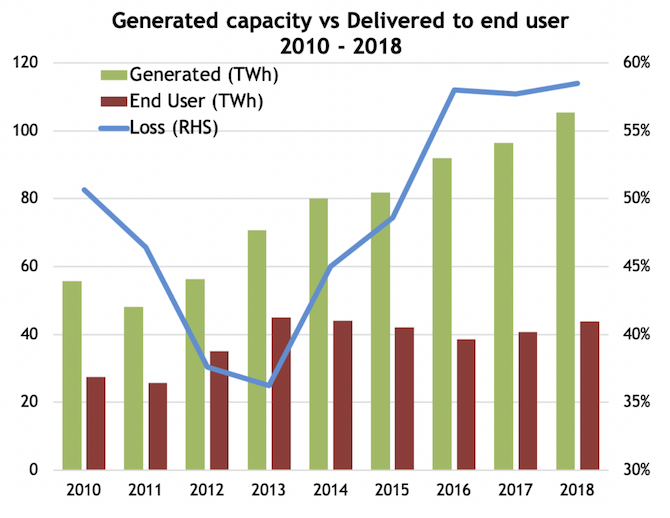

In turn, this increases the gap between demand and supply – in 2018 average demand was 17.7 GW vs. effective generated power of 11.9 GW. But this gap is only part of the story, as the electricity generated to meet demand does not mean that it was actually delivered to end users. The total electricity generated in 2018 was 105.4 terawatt-hours (TWh), but only 43.7 TWh reached end users for a loss of 58.5%. Most of these losses take place at the distribution stage, with technical losses stemming from age, conflict damage, poor maintenance accounting for two thirds, and non-technical losses, mostly electricity theft, accounting for a third. Technical losses are natural, however they occur at an extremely high rate in Iraq, as do non-technical losses. Stolen electricity – still consumed but not billed – is estimated at 17 TWh, and so the electricity delivered would rise to 61 TWh, equating to a loss of 42.2%. This dynamic can be seen below.

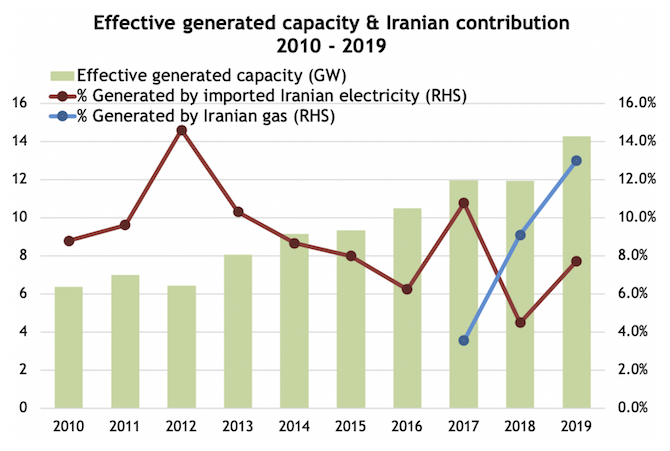

Electricity generated from Iranian electricity and gas imports accounted for 20.7% of that generated throughout 2019, and probably a much higher percentage during the peak summer months. These contributions from electricity imports from 2010 and gas imports from 2017 can be seen below.

Iranian gas imports were 7.0 billion cubic meters (BCM) in 2019, up from 4.1 BCM in 2018, and accounted for 31% of total gas consumed – up from 24% in 2018. Plans for increased domestic production include increasing captured flared gas to 16–19 BCM by end of 2021 from 12 BCM in 2019. Additionally, the fifth round of gas contracts call for replacing Iranian imports in three years, i.e. generating 7.0–10.0 BCM over that period from the current 3.5 BCM.

Assuming that the government executes these plans, in three years’ time this would replace the current electricity produced by Iranian imports. But demand is set to increase by 20% from current levels, meaning that the current the gap between supply and demand would increase by up to 20%. Moreover, planned capacity additions require additional fuel, which under existing plans is earmarked to replace imported gas. However, maintaining Iranian imports would significantly decrease their importance in power generation from the current 20.7%, and in the process Iraq would add meaningful capacity to address demand.

The goal posts are moving much faster than Iraq’s ability to approach them, and as such the US’s insistence on eliminating Iranian imports, far from achieving energy independence for Iraq, would instead exacerbate its energy vulnerabilities. Compounding these vulnerabilities is the massive investment spending needed to expand the grid’s capacity, currently unaddressed in the government’s structurally unbalanced budget, but which is ever more critical following the collapse of oil prices.

Iraq’s pathway out of this predicament, even at much higher oil prices, involves electricity tariff reform and the removal of energy subsidies, both the source of monumental waste and substantial market distortions. However, this requires a popular buy-in and for the increasingly alienated population to renew their belief in the post-2003 system’s legitimacy. It is here where the international community can help Iraq achieve energy independence.

Sources

The figures and charts used in the article are the author’s estimates, and are based on data from the Ministry of Electricity’s annual reports and conference presentations, the IEA, BP, MEES, Oxford Energy, and publicly available news sources. However, all errors and omissions are the author’s own.

The data used in the article exclude electricity demand and generation in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI). However, figures for locally produced and consumed gas include the KRI, and as such the Iranian-origin percentages of total gas consumed would be somewhat higher than the 31% and 24% used if the KRI was excluded.

Source

RSS Feed

RSS Feed