Iraq’s political crisis took a sharp turn for the worse this week when the country’s parliament was thrown into chaos over a government reshuffle that aimed to combat corruption and promote reform.

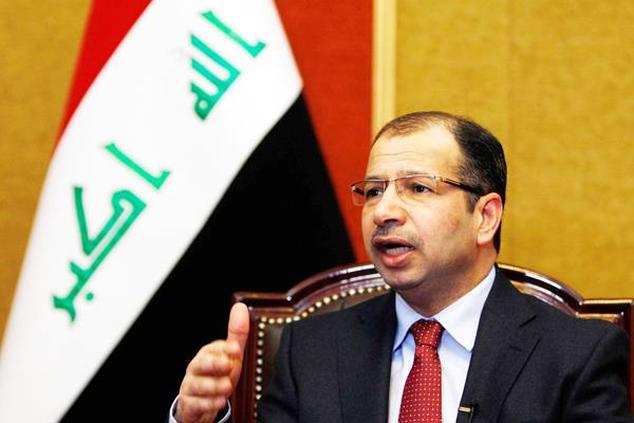

A group of Iraqi lawmakers announced on 14 April that they had ousted speaker Saleem Al-Jubouri after accusing him of blocking efforts to form a non-partisan government that could handle reforms.

The move, disputed by the major political blocs as unconstitutional, marked a tipping point in Iraq’s governmental crisis that started seven months ago with nationwide anti-graft protests.

Whoever chose to oust Al-Jubouri from his post was probably unaware of the possible resulting chaos. The removal of Al-Jubouri, a prominent Sunni politician, would most certainly have thrown Iraq’s leadership into further turmoil at a time when the country is embroiled in ethno-sectarian conflicts and a war with IS.

The escalation has already deepened the country’s ethno-sectarian divide.

The Sunni National Forces Alliance denounced the bid to oust Al-Jubouri as “a threat to Iraq’s unity” and warned that it could undermine the country’s delicate political process.

The Kurdistan Regional Government also announced it would not support any move to remove the country’s elected leaders.

Reacting to Al-Jubouri’s attempted ouster, the two main ruling parties in the Kurdistan Region warned that Iraq had “reached a dangerous stage” with both the government and the parliament in turmoil.

The Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) also reiterated the Kurds’ right to self-determination through a referendum which the two parties say will go ahead as planned.

The brawl over the stalled reforms has also deepened the power struggle in the country among rival Shia factions which was triggered by the government crisis.

Shia disagreements about how to handle the crisis are now out in the open.

Powerful Shia cleric Muqtada Al-Sadr, who has been leading anti-government protests, accused Iraqi politicians of trying to take advantage of the protests by adopting the pro-reform demands.

Comparing him to former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, Al-Sadr took aim at former prime minister and leader of the Islamic Dawa Party Nuri Al-Maliki, whom he blamed for trying to divert the anti-corruption reform from its “right course.”

Al-Sadr gave the country’s political leadership a three-day ultimatum to introduce a new cabinet of technocrats to stem corruption, warning that he would re-start the protests if they failed to do so.

The Islamic Dawa Party has accused Al-Sadr of trying to manipulate the anti-corruption protests “for narrow self-interest.”

“It is not strange that those who are trying to play the role of reformers want to impose their hegemony and threaten their political partners and intimidate them,” the party said in a statement.

It accused Al-Sadr of “leading organisations [practising] murder, corruption, sexual abuse and religious transgression.”

The question now is what will happen next. As Al-Ahram Weekly went to press, the political stalemate in Iraq was persisting with no signs of a breakthrough.

The crisis when it struck came from an unexpected source. The protesting lawmakers have acted out of frustration at the leaders of their blocs who have been finding pretexts to procrastinate in the process of reform.

In this sense, the parliamentarians’ rebellion has marked the end of what has been termed “consensual democracy” in Iraq, which in practice was nothing more than rule by an ethno-sectarian oligarchy claiming to represent the country’s different communities.

The protests have also unveiled the parliament as a place used by the entrenched oligarchs to exercise their wretched patronage system under the guise of partnership and a national unity government.

Under one scenario, the protesting lawmakers who have been occupying the parliament’s main hall will insist on electing a new speaker before moving ahead with plans to choose a new prime minister and probably a new president.

Not having the quorum necessary to enable them to achieve such a goal, the rebellious MPs, estimated at 120, will try to block the assembly from meeting, thus stalling the political process.

The second scenario is that the main political blocs will refuse to relinquish their patronage system and may decide to convene the assembly in a different hall or in another building, thus splitting the legislature into two camps.

Both the Kurdish and the Sunni blocs have declared that any resolution to the crisis should maintain the balance between Iraq’s ethnic and sectarian communities and the idea of partnership between them.

Iraq would not just be harmed in the possible chaos of a stalled parliament and the absence of a functioning government, but the vacuum would also make efforts to keep the country coherent significantly and irrevocably shrink.

Of course, there is also a third scenario, under which mediators, such as from the United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI), would try to bring the competing groups to the negotiating table.

But that would mean recognising the protesting MPs, especially if they establish themselves in a new bloc as an equal partner, and it would compromise the power-sharing formula which has been in place since the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

The alternative of any such mediation would only focus on the immediate government crisis and thus avoid the crux of the political conflict in Iraq, postponing the implosion of Iraq’s political system but not preventing it

Iraq has experienced an unprecedented roster of calamities. But the present parliamentary crisis is the country’s worst because it has hit the last institution that had been keeping the nation’s communities together.

Source http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/NewsQ/16140.aspx

RSS Feed

RSS Feed