The British government saw Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait as an “unparalleled opportunity” to sell arms to Gulf states, according to recently declassified secret documents.

The memos, released by the National Archives, reveal how in the build-up to the 1990 Gulf war ministers and civil servants scrambled to ensure Britain’s arms manufacturers could take advantage of the anticipated rise in orders for military hardware.

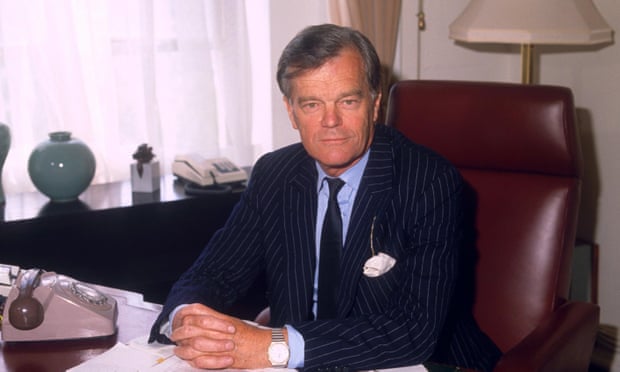

The documents include confidential briefings from Alan Clark, then defence procurement minister, to the prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, as he toured Gulf states on the eve of the war. The government’s efforts reaped dividends. The war provided a significant fillip for arms sales to the region and helped nurture a strong relationship that continues to this day.

Over 10 years, the report ranks Britain as the second biggest arms dealer in the world behind the US.

In a letter marked “secret”, written on 19 August 1990, days after Saddam Hussein’s forces had invaded Kuwait, Clark wrote a private memo to Thatcher in which he described the expected response from the US and its allies as “unparalleled opportunity” for the Defence Export Services Organisation (now known as the DSO).

Clark explained: “Whatever deployment policies we adopt I must emphasise that this is an unparalleled opportunity for DESO; a vast demonstration range with live ammunition and ‘real’ trials.”

Later in the memo, Clark adds: “I have pencilled a list of current defence sales prospects at the start of the crisis. These are now likely to be brought forward and increase in volume if we do our stuff.”

Other memos showed that Clark used meetings with the emir of Qatar and with the Bahrain defence minister to push for arms exports. In further briefings he identified the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Jordan as potential customers. Joe Lo, a researcher at Campaign Against Arms Trade, said the same countries were now being targeted by the UK for defence exports.

In one briefing document, drawn up on 7 August and marked “restricted covering confidential”, civil servants discussed possible defence sales.

Among the potential orders they were trying to bring in were 36 Westland Black Hawk helicopters from Abu Dhabi, in a deal worth £325m. Oman was listed as interested in buying Warrior desert fighting vehicles worth £55m, as well as placing an order for Challenger II tanks. Bahrain wanted to buy Hawk jets from British Aerospace, while, Saudi Arabia was listed as being interested in a £200m deal for seven hovercraft.

Clark believed that sharing intelligence with the Gulf states in the run-up to war could be a useful marketing tool for the arms industry. He advanced a plan for a senior intelligence officer to make weekly visits to Gulf states to share “highly sanitised” briefings that would not be in “violation of our understandings with the US”. Clark was clear about the benefits of such visits, noting that they would “provide a useful entree for the DESO representative when appropriate”.

The documents show how Clark visited Gulf monarchs in the days leading up to the war to underline UK support for them and stress the speed and response of the British military response. He told Thatcher that his instinct was to “go in heavily and urgently” against Iraq in the impending conflict.

Charles Powell, Thatcher’s private secretary, told Clark in a memo that he wanted him to use his visit to Gulf rulers to point out that the UK has been faster and better at responding to help its Gulf allies than France, an arms export rival.

He also asked Clark to visit the smaller Gulf states which felt that the UK “has not been sufficiently attentive to their security needs and concerns”.

The issue of exports was clearly a sensitive issue for ministers, however. In one memo to Powell, William Waldegrave, minister of state for foreign and Commonwealth affairs, opposed the government’s decision to raise Saddam’s human rights abuses, saying that it provoked the inevitable question of “why did you go on doing so much business with him?”

Source

RSS Feed

RSS Feed