The parliamentary remnant illegally convened a session, voted amongst itself to dismiss CoR Speaker Salim al-Juburi, and elected a new provisional speaker. Party discipline and cohesion is devolving, though the Kurdistan Alliance, ISCI, and Badr Organization – each of which has received benefits in the evolving cabinet reshuffle – appear to have retained control of their members.

Senior political leaders are meeting. Longtime allies Ammar al-Hakim and Jalal Talabani met in Suleimaniyah on April 13, presumably to discuss ISCI cooperation with the Kurdish Alliance, while rumors state that Muqtada Sadr is in Lebanon, as is Jawad al-Sharistani, the son-in-law and representative of Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani.

Although these leaders may be trying to stave off government collapse, they may not be able to overcome the parliamentary entropy. Street protests have reignited in advance of Friday prayers. Parliamentary means, protests, or force may topple the current government.

Prime Minister Abadi’s cabinet reshuffle has floundered as political blocs hijacked the initiative in a bid to preserve their representation and access to patronage within the cabinet. PM Abadi announced the cabinet reshuffle on February 9 in an effort to improve government performance, remove political interests from the cabinet, and reassert control over the government. ISW assessed on February 15 that PM Abadi’s attempt to reshuffle the cabinet might lead to his ouster.

Abadi’s efforts this spring have largely failed, as they did in August 2015. Members of political blocs, including Former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki’s State of Law Alliance (SLA), have more openly discussed whether PM Abadi should remain premier. Others, primarily those that are opposed to SLA leader Nouri al-Maliki, have insisted that PM Abadi cancel his membership in the Dawa Party, nominally to have an “independent” Prime Minister, but actually in order to pry PM Abadi away from Maliki and his grip on the Dawa Party. Meanwhile, Maliki and pro-Iranian elements within the pan-Shi’a political body, the National Alliance, worked to prevent PM Abadi from conducting any meaningful reforms. Most notably, the National Alliance formed a unique sub-committee on March 27 composed of a senior ISCI member, Hamid Maleh, and two Iranian proxy actors, Badr Organization leader Hadi al-Amiri and Popular Mobilization Commission chairman Faleh al-Fayadh. Maliki and pro-Iranian elements likely wanted to control the direction of PM Abadi’s reforms, while ISCI’s representation was likely more a product of its fence-sitting position as it attempts to re-position itself as a more powerful force within Iraqi politics, as outlined in ISW’s March 25 assessment.

Iraq’s political situation has degenerated spectacularly. Political blocs have been unable to select a new cabinet despite weeks of negotiations and horse-trading, leading to frustration not just among the Iraqi populace, but within the political blocs themselves. On April 12, several political blocs fractured as CoR members rebelled against the apparent wishes of their respective leaders, barricading themselves within the CoR building, forming a rump CoR, and illegally voting a new CoR Speaker to replace current Speaker Salim al-Juburi. The situation has degenerated to the point that party discipline among a large number of political blocs has collapsed, with rebelling CoR members taking positions dramatically different from those of their bloc leaders. The current political crisis threatens the stability of Iraq in an unprecedented manner, and the crisis could see the government collapse.

Background

PM Abadi’s reform initiative has benefited from the support of Sadrist Trend leader Muqtada al-Sadr, who has positioned himself as the head of a popular anti-corruption and pro-reform movement in the wake of Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani’s withdrawal from Iraq’s political scene in early February. Sadr’s support has come largely in the form of popular street demonstrations and a large sit-in organized in front of the entrance to the Green Zone in central Baghdad. Thousands of Sadrist supporters have called for reforms, and Sadr himself evenjoined the sit-in movement, setting up a tent in the Green Zone on March 27 to pressure the political blocs to conduct reforms and select a new cabinet of technocrats. Sadr’s personal sit-in put heavy pressure on the political blocs to acquiesce to PM Abadi’s demands to select a new cabinet to PM Abadi’s specifications.

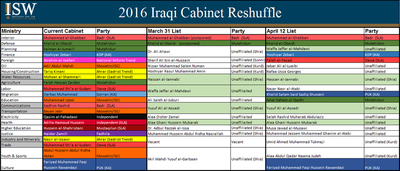

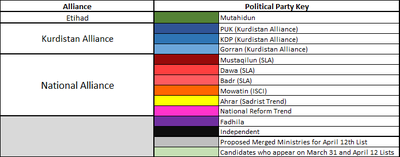

PM Abadi, bolstered by Sadrist Trend leader Muqtada al-Sadr and large demonstrations in favor of reform, sent a list of potential replacements for his cabinet to the CoR on March 31. In defiance of Maliki and the preferences of pro-Iranian interests, the list was almost entirely composed of technocrats and had no major political party members represented. The only exceptions were Defense Minister Khalid al-Obeidi, a member of the Sunni Etihad bloc, and Interior Minister Muhammad al-Ghabban, a member of the Badr Organization, citing the need to maintain stability in these ministries due to the ongoing fight against ISIS. Cleverly, the technocrats included independent Kurds as nominees for the important Oil and Housing Ministries in a bid to win the support of the Kurdistan Alliance. The Kurdish blocs had previously insisted on the need for current Kurdish ministers to retain their positions in order to preserve Kurdish representation within the government.

While presenting the list at the CoR, PM Abadi deliberately thanked Sadr, who ended the pro-reform sit-in his followers had been conducting in front of the Green Zone since March 18, even though Sadr did warn that he would withdraw confidence from if the cabinet reshuffle did not succeed. PM Abadi likewise noted that the CoR needed to vote on the new cabinet within 10 days, though at some point, the voting session was delayed two additional days to April 12 for unclear reasons.

Multiple parties opposed the new cabinet that cut them out of government. Sunni blocs complained that the new cabinet was not representative of the people. The Kurdistan Alliance had insisted on the need for the Kurdish blocs to be consulted before any Kurd was nominated, but later simply resorted to intimidation to force the Kurdish technocrats to withdraw their nominations in a bid to force PM Abadi to keep the current Kurdish ministers in the government.

ISCI, on the other hand, recommended a “National Reform Initiative” aimed at building an advisory council to PM Abadi composed of the leaders of all major political blocs, as well as a committee representative of the political blocs to advise PM Abadi on the new cabinet’s composition. The ISCI meeting formed the basis for future efforts by political blocs to come to a consensus agreement on how to approach the reform process, as it effectively recommended a cross-party power-sharing agreement within the government and constraints on PM Abadi’s powers.

The cabinet reshuffle process also sparked a flurry of meetings between political bloc leaders as they attempted to find a solution to the protracting political crisis. The meetings were not just among political allies, but among prospective allies as well; ISCI’s Ammar al-Hakimmet with Badr Organization, Etihad members met with al-Ahrar Bloc members, and all blocs met with some combination of the three presidencies: Prime Minister Haidar al-Abadi, President Fuad Masoum, and CoR Speaker Salim al-Juburi. These meetings were likely conducted for the primary purpose of negotiating the outcome that would bring the most benefit to the political blocs.

Political pressure eventually led PM Abadi to retreat, and he invited political blocs to submit their own technocratic nominations for consideration. Political blocs inevitably submitted new political candidates for the technocratic cabinet, though not all party members accepted their nominations, indicating that party discipline was breaking down. One member of the Sunni bloc Iraqiyya Alliance, Qutaiba al-Juburi, stated he withdrew his nomination after Iraqiyya selected him for a ministerial position, citing the need to have a non-partisan cabinet. The Kurdistan Alliance did not even bother to submit nominations and remained the strongest opponents of the concept of the cabinet reshuffle, insisting that their current ministers retain their positions.

Yet going into the April 12 CoR session, the political blocs and the three presidencies appeared to have an agreement with one another, even signing a document on April 11 laying out the framework for a national reform initiative similar to the ISCI reform initiative, laying out the cabinet reshuffle process, and identifying key legislation that needed to pass in the CoR. They even appeared to agree to preserve political interests in the cabinet; they reportedly agreed to do away with the March 31 nominations and keep 22 ministries instead of the proposed 16 in an attempt to ensure that all blocs had representation – and thus, access to patronage – in the cabinet. This contrasted with the weeks leading up to the March 31 CoR session that saw different political blocs leaking different lists of cabinet members to the media in a bid to influence the direction of the reform process. However, several unspecified blocs reportedly boycotted the meeting.

Week of March 31: Maliki Attempts to Oust PM Abadi

The leader of the SLA, Vice President Nouri al-Maliki, attempted to oust PM Abadi. The U.S. and Iran were meanwhile applying leverage to ensure that PM Abadi did not leave office. U.S. support for PM Abadi during the reshuffle has been particularly strong and visible; U.S. officials, including Secretary of State John Kerry, met with the leaders of numerous political blocs in Iraq on April 8, and U.S. Vice President even phoned PM Abadi multiple times to express his support. The U.S. reached out to political blocs, including ISCI and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), to discourage any attempt to remove PM Abadi. For the U.S., retaining PM Abadi in his position is critical for maintaining ongoing anti-ISIS efforts. PM Abadi willfully accepts U.S. and Coalition assistance as far as is possible without sparking the ire of Iran and its proxies. He also actively resists pressure to conform to Iranian directives, albeit weakly. More importantly, there are no obvious candidates to replace PM Abadi should he leave the premiership for any reason, and a political crisis stemming from a collapsed government could severely undermine anti-ISIS efforts, reversing progress and allowing ISIS to take advantage of the unrest to re-establish its capabilities and launch attacks.

Iran also blocked efforts to oust PM Abadi, reportedly sending its top regional power-broker, Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC)-Quds Force commander Qassim Suleimani to rein in Maliki’s initiative. For Iran, keeping PM Abadi maintains stability at a time when it is preoccupied with events in Syria. Iran may also benefit from Abadi’s weakness, which allows it to maintain its status as a powerbroker among Iraq’s Shi’a factions. Maliki, in contrast, is a centralizer and consolidator of power. Finally, the Iraqis may not be able to push a more pro-Iranian premier through the confirmation process.

It is not clear when Maliki attempted to replace PM Abadi, and it is unclear whether or not Maliki attempted to replace PM Abadi before or after the March 31 CoR session that saw PM Abadi submit his list of technocratic nominations. But Maliki’s attempt to remove PM Abadi, and the cabinet’s change from a technocratic one to one of political party interests, demonstrated PM Abadi’s vulnerability and his inability to impose his will on the political blocs.

April 12: The CoR Collapses

The crisis over the cabinet reshuffle escalated even further on April 12, when PM Abadi submitted his new list of nominations to the CoR for a vote. The new list was a compromise between PM Abadi’s March 31 list, which consisted entirely of technocrats, and the appointments of political blocs. The April 12 list recommended that: four of the original 16 nominated technocrats stay in the new cabinet; a number of new technocrats take other positions; and that the Interior and Defense positions remain untouched due to their importance in the ongoing fight against ISIS. Yet the new cabinet also retained a number of senior political actors. The Kurdistan Alliance had collectively threatened to boycott the CoR session or even withdraw from government if their ministers did not remain in their current positions, so PM Abadi had to concede positions to the bloc in order to secure their votes. Current Culture Minister Fariyad Muhammad Rawanduzi and Finance Minister Hoshyar Zebari therefore kept their positions, and a third position, the Migration Ministry, went to a PUK member. The new list also recommended Faleh al-Fayadh, the National Security Adviser and the Chairman of the Popular Mobilization Committee (PMC), as the new Foreign Minister. Fayadh, a figure who is close to both Maliki and Iran, is the polar opposite of a technocrat, and was likely pushed on PM Abadi by Maliki. The new cabinet thus represented a step back from the March 31 list that sought to remove political interests from government.

It is not clear if PM Abadi ever wanted to submit the April 12 list; an anonymous source “close to PM Abadi” stated that PM Abadi submitted both the April 12 compromise list and re-submitted the March 31 technocrats list, but that somehow only the April 12 list was brought to a vote.

The April 12 CoR session represented a flurry of confusion and delay tactics. Speaker Juburi stated that PM Abadi needed to submit either the resignations or the notifications of dismissal for the current ministers before the new ministers could be selected, likely in an attempt to delay the vote, though CoR members called for the new list regardless. The CoR session briefly adjourned, and PM Abadi, Speaker Juburi, and the heads of political blocs met in private to discuss the reform process. The blocs could not come to an agreement on the new cabinet, and so Speaker Juburi, after reconvening the CoR session, announced that the vote would be delayed until April 14.

Juburi’s announcement led to mayhem in the CoR. Members swarmed the Speaker’s podium, yelling and chanting against political quotas and protesting the delay. One outraged CoR member even threw several chairs at the podium. In a bizarre spectacle, several CoR members staged a farcical vote and half-jokingly selected a new CoR Speaker, a senior SLA member from Babil Province, as well as a Speaker’s deputy and rapporteur. Shortly thereafter, protesting members of the SLA, Etihad, and al-Ahrar barricaded themselves inside of the CoR building and announced a sit-in inside the CoR hall to force an emergency CoR session to convene on April 13. Some protesters also called for the CoR to vote on the original technocratic list instead of the April 12 compromise nominations. An al-Ahrar member stated that 115 CoR members, including 40 female members, stayed in the CoR overnight in protest.

One of the other demands of the protesters was the removal of the three presidencies from their positions and the dissolution of government. Shortly before PM Abadi presented the list of new nominations, a movement began within the CoR to collect signatures for the removal of the three presidencies. Ahmed al-Juburi, a member of the Iraq Alliance, a primarily Sunni bloc, stated during the CoR session that 33 CoR members had signed a document calling for the removal of the three presidencies and the dissolution of the government for failing to meet the demands of the people and dragging the country into a “spiral of crises.” Throughout the course of the day, the number of signatures fluctuated from anywhere from 105 and 114 to 150 and 164.

April 13: Political Party Discipline Breaks Down

The sit-in and protest appeared to be less of an initiative organized by political blocs’ leadership and more of an emotional response to the crisis. There did not appear to be any one bloc that showed up in their entirety to the CoR sit-in, which saw several competitors sitting in solidarity with one another; Hakim al-Zamili, a senior member of the Sadrist Trend, and members of al-Ahrar Bloc sat next to Aliyah Nassif, a key ally of Maliki, Sadr’s primary rival, as well as Hassan Salim, a CoR member affiliated with the Iranian proxy militia Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq, a rival of Sadrist militias. Similarly, members of other blocs, such as the Kurdistan Alliance and ISCI, did not appear to participate in the sit-in. This indicates that these blocs maintained party discipline and stuck with the directives of the political blocs’ leadership, which likely agreed to delay the CoR vote.

Discipline broke down in other blocs. The leadership of the political blocs, if they commented at all, voiced disapproval of the CoR protest. The Sunni Mutahidun party condemned efforts to undermine procedure in the CoR, though members appeared to participate in the sit-in. While Sadrist Trend members participanted in the CoR sit-in, members of a Sadrist demonstration that reached into the thousands occurring in Tahrir Square on the same day shied away from supporting the prospect of removing the three presidencies.

The overnight sit-in forced Speaker Juburi to call an emergency CoR session to vote on the new cabinet on April 13. He reportedly planned to present both the March 31 and the April 12 list to the CoR for voting. Only 174 CoR members were present – barely over a quorum, which requires 163. However, no vote could be held as the CoR again fell into chaos. An al-Ahrar Bloc member, Awad al-Awadi, demanded at this point that Speaker Juburi “act with courage” and present the motion to dismiss the three presidencies, reportedly signed by 171 CoR members, after which CoR members began chanting for Speaker Juburi’s removal. At some point, a physical altercationbetween Aliyah Nassif and PUK member Ila Talabani broke out – reportedly because Nassif was sitting in Talabani’s chair – that led to CoR members to throw punches and bottles of water at each other. The chaos led Juburi to suspend the April 13 CoR session, though CoR members continued to protest inside of the CoR building.

Speaker Juburi, in a bid to end the demonstration, went to President Masoum and recommended that he dissolve the CoR and call for early elections. The move represented a bid by Speaker Juburi to re-impose discipline in the CoR and – it would have been highly unlikely for Iraq to be able to conduct any elections given the security environment. Speaker Juburi also met with political bloc leaders and with PM Abadi to discuss the ongoing crisis.

The CoR protest movement was bolstered even further when Iyad Allawi, the leader of the secular Wataniya Bloc, joined the protesters in the CoR building. Allawi has been one of PM Abadi’s strongest critics, and has called for PM Abadi’s removal on numerous occasions in the past. Allawi likely joined the demonstrators in a bid to boost his political stature, as he has declined as a relevant political figure in recent years, going from nearly capturing the premiership in 2010 to holding only 21 CoR seats today. It thus appears that Wataniya and al-Ahrar are the two blocs that have wholly joined the CoR protesters, as these are the only two blocs whose senior leaders have participated in the CoR sit-in.

April 14: The Rebel CoR Bloc Illegally Ousts Speaker Juburi

Events came to a head when, on April 14, Speaker Juauri did not attend the CoR to call for its scheduled session. Neither did PM Abadinor President Masoum, who were supposed to attend, nor, for that matter, members of political blocs who had not joined the protest movement. The notable absences indicate that the political bloc leaders and the three presidencies decided to delay the CoR session until they could re-impose discipline on the protesting CoR members. Political blocs, who had been attempting to preserve their interests within the new cabinet, were losing control over their ability to insert political candidates into the new cabinet, as the rebelling members of their own blocs had begun actively resisting partisan nominations and were actively calling for a technocratic government and new political leadership. The leadership of the political blocs were thus confronted with the problem of a cohesive protest movement working against their own parties’ interests and threatening the stability of the government. The biggest problem was that the rebelling CoR members were acting as a single bloc, larger than any other in the CoR by at least 40 seats and taking up more than a third of the CoR’s seats, making them the most powerful force in CoR decision-making.

The April 14 CoR session thus did not reach quorum – according to the Parliamentary Media Directorate, only 131 rump CoR members were present, below the 163 members necessary for quorum. This number was not confirmable, particularly because security forces prevented the Parliamentary Media Directorate employees from entering the building for an unspecified reason. The lack of quorum did not stop the rebel CoR members from holding an illegal session under the chairmanship of Adnan al-Janabi, a leader in a prominent Sunni tribe in Babil Province and a member of Iyad Allawi’s Wataniya, who stated that 171 members attended the session, enough for quorum. Another CoR member, SLA member Kadhim al-Sayyadi – an unhinged SLA member best known for attempting to shoot another CoR member during a television interview in November 2015 –stated that the April 14 CoR session was a continuation of the previous day’s CoR session, and that because quorum was reached in the previous day’s CoR session, the April 14 session was legal. It is most likely that quorum was not reached.

The CoR members effectively formed a rump parliament, a parallel CoR with shrunken membership, and upended the sitting leadership of the properly elected and constituted CoR. They voted to remove Speaker Juburi, First Deputy Humam Hamoudi of ISCI, and Second Deputy Aram Sheikh Muhammad of the Kurdistan Alliance, according to their spokesperson, Haitham al-Juburi, a member of a small party within the SLA. The rebelling CoR members unanimously selected Wataniya member Adnan al-Janabi as interim CoR Speaker. They also formed a committee of three unspecified people to select a new CoR Speaker for the April 16 CoR session. The parallel CoR insisted that it was formed without political party interference. All of the CoR members participating in the rump parliament – a term referring to a parliament that exists parallel to the legal parliament but also composed of legal parliament members – are members of political blocs, and are therefore making a deliberate break with their parties’ leadership. They are attempting to form a new political bloc.

A rebel Etihad member, Ahmed Jarba Mutlak, demanded that President Masoum withdraw confidence from PM Abadi, a move that would collapse the government. Masoum would thus, in accordance with the constitution, need to give the right to form a new government to the largest bloc. Jarba noted that the largest bloc was composed of rebelling members of the rump. This indicates that there are efforts to coalesce the rebelling CoR members into a cohesive political force at odds with the leadership of the political blocs. According to Wataniya Bloc chairman Hassan Chuwairid, a participant in the CoR protest, the rebelling CoR members would even hold talks with other blocs to choose the new Speaker.

The backlash from the political blocs against the attempt to oust Speaker Juburi was swift. The Speaker stated that the session was not legitimate as no quorum had been reached. The Kurdistan Alliance and Etihad, of which Speaker Juburi is a member, also rejected the motion as unconstitutional, though the Etihad CoR Bloc chairman, Ahmed al-Masari, continued to insist on the need to question PM Abadi and sack him if necessary. The leader of Badr Organization’s CoR bloc, Qassim al-Araji, called for the need to maintain “social cohesion” and warned that “significant differences” between political blocs could result in a degenerating security situation.

Seeking Stability amongst the Shi’a

The prospect of a collapse in government unnerves the regime in Iran, and the position of the Badr Organization, an Iranian proxy group, is indicative of Iran’s unease about Iraq’s political crisis. Though PM Abadi is unpalatable to Iran due to his willingness to accept large amounts of U.S. support in the fight against ISIS and his unwillingness to willingly bow to Iranian directives, Iran presently favors stability in Iraq over a change in government, in large part because Iranian military forces and its Iraqi proxy militias are preoccupied with fighting in Syria.

It is also possible that Muqtada al-Sadr has become unnerved by the direction of events. Sadr publicly distanced himself from al-Ahrar Bloc during his sermon in Tahrir Square on February 26, even referring two of its most senior members for investigation on corruption charges and detaining another. The Sadrist sit-in in front of the Green Zone was marked by a lack of participation by al-Ahrar Bloc members and a reliance on Sadr’s charitable foundation, the Office of the First Martyr al-Sadr, a further indication of separation between Sadr and al-Ahrar. It is thus possible that Sadr has lost control over al-Ahrar Bloc, as he has conspicuously issued no statement in support of the rebelling CoR members, despite the prominent participation of al-Ahrar Bloc members in the protest. It is important to note that Sadr did warn that he would withdraw confidence from PM Abadi on March 31 if the cabinet reshuffle did not succeed. However, Sadr’s behavior indicates that al-Ahrar Bloc may have misinterpreted or gone against Sadr’s orders in some measure; al-Ahrar Bloc in all likelihood remains loyal to Sadr, but may not necessarily be under Sadr’s full control.

Much of the Shi’a political establishment will seek stability, as will the Iranian regime. Iraq’s most prominent Shi’a powers are thus likely seeking a way to defuse the situation before the government collapses. On April 13, an anonymous political source stated that Sadr arrived in Beirut on an “unofficial visit,” reportedly to “consult” with Lebanese Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah. Sadr reportedly joined SLA leader Nouri al-Maliki, Sadr’s rival, who had arrived in Beirut on April 11. In addition, their meeting coincided with a visit to Lebanon by Jawad al-Shahristani, the representative and son-in-law of Iraq’s highest Shi’a religious authority, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, who led a delegation to Lebanon on April 14. There is no confirmation that these figures met, either separately or all together, but it is highly unlikely that these arrivals were coincidental. It is more likely that Iraq’s major Shi’a powers arrived in Beirut to discuss a way to address the crisis in Iraq, possibly with Nasrallah or a representative of the Iranian regime, such as IRGC – Quds Force leader Qassim Suleimani Iran’s favorite power-broker for the region.

Conclusion

Iraq’s political crisis has reached a dangerous threshold – political blocs still have not reached an agreement on the new cabinet and are experiencing internal fracturing. The result could be a collapse of the Iraqi government: the CoR could vote no-confidence in PM Abadi or he could resign. The CoR could lose a quorum and cease to function as it did in 2006. The rump CoR could persist and create a parallel government. A judicial challenge to the constitutional crisis that ensues would likely favor Maliki, as long as Medhat Mahmoud, the head of the Judiciary and a longtime Maliki ally, remains. CoR Speaker could also dissolve the CoR and call for early elections at the threat of facing mounting protests and instability across the country. Any of these prospects practically ensures that there will be no possibility of recapturing Mosul in 2016.

The consequences of Abadi’s fall or a constitutional crisis could be disastrous for the stability of the country. Ongoing street demonstrations and confusion surrounding the process of selecting a new government could expose the country to attacks by ISIS aimed at further exacerbating the situation. The security situation could worsen as Iraqi Shi’a militias descend on Baghdad in a bid to influence the political climate, an outcome that could increase the possibility of intra-political party violence in Baghdad. Alternatively, formal institutions of the Iraqi Security Forces could become involved, although ISW has observed no such indicators as of April 14. Iraq’s Kurds could take concrete steps towards secession if efforts to form a new government exclude Kurdish blocs. The government will make no progress in addressing the worsening economic situation, the return of internally-displaced persons to their homes, or the reconstruction of damaged parts of the country. Moreover, the progress of the war against ISIS will be suspended in limbo, as the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) will be conducting operations for a failed government, and make it far more difficult for the U.S. to conduct anti-ISIS operations.

ISW previously assessed that a vote of no-confidence against PM Abadi was the most dangerous rather than the most likely course of action because no compromise candidates exist to take his place. It is still unclear if the political blocs could get behind any political leader. Maliki will not likely be able to form a government because of the degree of animosity other political blocs have towards him. National Alliance chairman Ibrahim al-Jaafari, a close ally of Iran, is the closest thing to a consensus candidate amongst the Shi’a parties, but even he would face serious obstacles as a candidate. These establishment figures remain possible candidates for the premiership only if the political blocs manage to rein in their rebelling CoR members. Time will tell if the rebelling CoR members will coalesce into a functioning political bloc capable of challenging others in the CoR. But the formation of a rump CoR and growing calls for the dissolution of government, in defiance of the wishes of the political bloc leaders, Iran, and the U.S., bode ill for PM Abadi’s ability to remain in office and effective. Political blocs may still put their differences aside and vote to retain confidence in PM Abadi by selecting a new cabinet, but that remains unlikely, as political blocs remain undecided on what the new cabinet should look like. A vote of no-confidence or a constitutional crisis in which the formal, elected parliament no longer functions are more likely scenarios. The U.S. must therefore prepare for the possibility that the post-Abadi Iraq will arrive sooner than expected, with all of the instability that will follow.

Source http://iswresearch.blogspot.co.uk/2016/04/iraq-government-collapse-likely-as-rump.html

RSS Feed

RSS Feed