Ramadan is drawing to an end. In Baghdad, imams lead pious worshippers for Taraweeh prayers in the evening. The recitation of dua echoes across neighbourhoods like a chorus of pleading voices ascending to the heavens above.

Iraq is a wounded nation still wading through the murky waters of adversity.

Around sunset, just before families gather for the iftar meal to break their fast, the city’s destitute come wandering, going from door to door. They are mostly children who lost parents in one of the many days of blood that have soaked Iraq’s calendar since 2003.

They are pale and hungry, and there are so many of them, almost everywhere.

Not even in the wretched years of the 1990s, when the UN sanctions sent so many children to early deaths, were there so many beggars on the streets of Baghdad.

A lethal failure

Nightfall is also the time that militiamen and terrorists come out to play, their bullets and rockets punctuating the grim silence.

The latest victims include Ihab al-Wazni, an activist shot dead outside his home in Karbala in the early hours of Sunday 9 May. Just 24 hours later, journalist Ahmed Hassan survived an assassination attempt in al-Diwaniyah.

The state never runs out of promises that it will punish and hold accountable the perpetrators, but ordinary Iraqis continue to die so easily. All in all, Iraq Body Count recorded 235 violent civilian deaths in the first four months of 2021 alone.

The assassinations, says a statement from the Iraqi High Commission for Human Rights, are proof that the security system is failing to protect activists.

It’s not just activists receiving bullets. The deadly lawlessness in Iraq includes frequent rocket attacks on military camps and airports, militia parades in the capital and ISIS terrorists wreaking havoc in Diyala and beyond.

How are these attacks allowed to become part of everyday life, even though a big chunk of the state’s budget funds a sprawling security apparatus that is supported by a global coalition?

Ordinary Iraqis know the answer, and they are frightened.

“We are living a big lie,” says Baghdad resident and activist Nour Zidan. “Al-Wazni was killed just three days before Eid al-Fitr, imagine what his family must be going through right now.”

A culture of impunityIn a recent media appearance, Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi said that his government is the first to fulfil a commitment to investigate security breaches.

His tenure might have seen a few arrests, but also a series of ongoing, deadly security breaches, amid blatant threats and intimidation.

The faces of fallen protesters graffitied on the streets of Baghdad are a reminder of a bloodbath whose architects are still unpunished.

In October 2019, Iraq’s youth took to the streets, to demand a dignified life akin to that enjoyed by many of their rulers’ families abroad. They were slaughtered like sheep by security forces and unidentified gunmen, under the former government of Adel Abdul Mahdi.

Hundreds were killed and thousands were wounded in an unequal standoff that is still being falsely described as “clashes” by international media.

That year, the usual chaos, corruption and death was a part of everyday life for most Iraqis.

Yet some scholars, whose fine hotel rooms offer no view of Baghdad’s impoverished alleys, reminisce about Abdul Mahdi’s time. To them, it was a time when the country was moving along “a very promising trajectory”.

Abdul Mahdi was among the officials attending the reception ceremony Pope Francis in Baghdad. He appeared grinning from behind his mask on live TV – not in an orange jumpsuit, as the families of dead protesters, who blame him for the security lapses, might have preferred.

Of course, the camaraderie of the ruling elites means that lethal failure recedes in the rear view mirror, along with the dead bodies. This culture of impunity ensures that civilian deaths continue apace, outlaws are emboldened, and misery remains the norm.

“As long as there are arms outside state control, every day will see someone else shot dead,” Zidan laments.

A wasteland

Iraq’s recent past suggests its future is bleak. Its present fulfils the poet Muhammed Mahdi al-Jawahiri’s premonition of a long-lasting agony:

“I see a horizon lit with blood

And many a starless night

A generation comes and another goes

And the fire keeps burning”

[From ‘My Brother Jafar’, translated from Arabic by Sinan Antoon, and published in The Nation]

Seven decades have passed since he wrote these lines in 1948. The fire still burns.

Al-Jawahiri spent months telling his peers in his home city of Najaf about his discoveries in Baghdad. Today, the capital, his “mother of orchards”, barely has a handful of gardens. It is a wasteland where palms are dried, roads are broken – and people are broken, too.

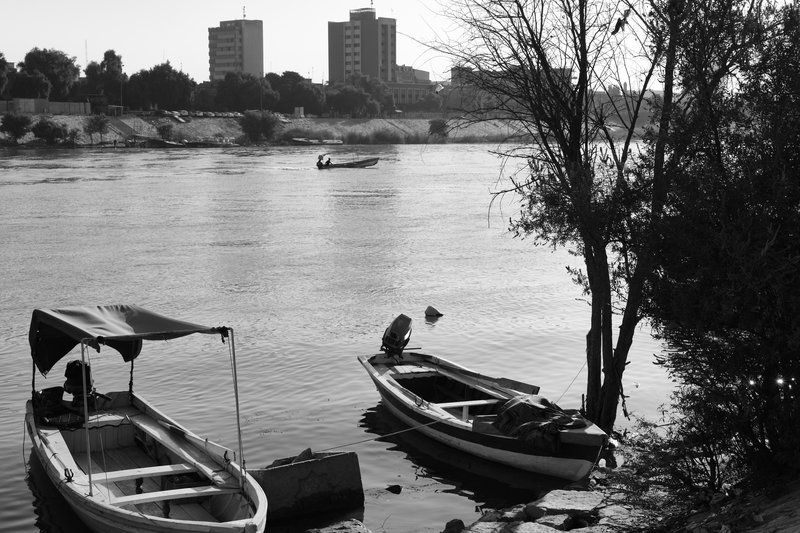

Stand at the edge of the al-Shawaka neighbourhood, on the western side of the Tigris, then lower your gaze, and there it is: a blanket of filth and garbage covering the banks of a dying river.

When the sun rises in the east, slender boats glide along the shimmering surface of the water. They ferry passengers to and from al-Nahar street for half a dollar each.

But these boats are not allowed to go downriver to al-Sinak bridge and beyond, near the off-limits bank of the “Green Zone”. US troops are gone, but the securitisation of public space in Baghdad lingers on, and not only in the form of ugly T-Walls blocking the streets.

In the maze of hidden souqs obscured by ancient mosques, on the eastern bank of the Tigris, herds of young porters eke out a living the hard way. They snake through a labyrinth of crammed alleys, pulling loaded carts for a few dollars a day.

That is, until the Central Bank devalued the dinar in late 2020, and their wages were cut by the merchants, who in turn suffered plunging sales.

“The souq stopped,” Ali Tawfiq, a 20-year-old porter, says. “This pushed many of us porters to quit working in the market. I rarely go there nowadays. It’s not worth it anymore.”

Chaos continues

In March, the Ministry of Health attributed its difficulty containing the pandemic to the public’s non-adherence to protective measures. But the soldiers who man checkpoints don’t wear masks either, and even religious processions where large numbers of people gather were permitted by the state.

Restaurants in Baghdad’s older, neglected downtown served their regulars as usual. Loyal, elderly patrons frequented their favourite cafés, played backgammon and sipped tea in the sun. Young men stared into their phones and sucked on their shishas beneath clouds of smoke.

Neither there, in the souqs where porters like Tawfiq work, was there any sign of presence of health-awareness teams making frequent visits. “No one showed up,” he says.

Iraq is also way behind in the race to vaccinate its people. Stumbling, really. No more than 1% of Iraq’s population of 40 million has been vaccinated so far, and it is not just because of apathy or misinformation.

In recent weeks, desperate people queued up for hours, crammed inside al-Yarmouk hospital in Baghdad, only to be turned away. On 20 April, a Tuesday, dozens of people were told that Pfizer vaccines would only be available on Mondays.

When the next Monday arrived, they stood in lines from 6am, only to be told that no vaccines were available that day.

Dozens of people filed into the hospital again the following week. No social distancing was followed, because there were no guidelines in place. This time they were told the available vaccines were reserved for those awaiting their second dose.

The people filed out, dragging their disappointment along. Unsure when they are going to be vaccinated, bitter complaints fell from their lips.

Source (Click Here)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed