But from an American point of view, the most striking part of the report is how foreseeable the disaster that unfolded after the invasion was.

When you read the British government’s intelligence assessments, they predict, plus or minus a few details, exactly what happened after the war. The UK had ample warning that Iraq would collapse after the invasion and make the problem of terrorism worse — but it went to war anyway.

Why? Basically, the report suggests, because the US decided to. Then-UK Prime Minister Tony Blair decided that the UK couldn’t afford the hit to the US-UK relationship that would come from seriously challenging the Bush administration’s rush to war, so he decided to back America to the hilt.

UK intelligence predicted Iraq’s collapse

In March 2002, a year before the invasion, the UK took a hard look at the potential consequences of an invasion. Its military intelligence organization, called the Defence Intelligence Service (DIS), released an internal report on the likely consequences of a US-UK invasion. Its contents were remarkably prescient.

It predicted that sectarian tensions, as well as the legacy of authoritarian rule, would pose a serious threat to post-invasion stability.

"Sunni hegemony, the position of the Kurds and Shia, enmity with Kuwait, infighting among the elite, autocratic rule and anti-Israeli sentiment will not disappear with Saddam," the DIS report explains. "We should also expect considerable anti-Western sentiment among a populace that has experienced ten years of sanctions."

Fixing these problems, the DIS argued, would require an extraordinary and lengthy commitment of American resources.

"Modern Iraq has been dominated politically, militarily and socially by the Sunni. To alter that would entail re-creation of Iraq’s civil, political and military structures," they write. "That would require a US-directed transition of power (ie US troops occupying Baghdad) and support thereafter. Ten years seems a not unrealistic time span for such a project."

These were not hard predictions to make. DIS’s predictions stemmed from simply taking a hard look at the basic structure of Iraqi society — a majority Shia country that had long been controlled by a Sunni sectarian dictatorship. Indeed, the Chilcot report finds that it was hardly alone in warning of pitfalls in the post-invasion world.

"The information available to the Government before the invasion provided a clear indication of the potential scale of the post‑conflict task and the significant risks associated with the UK’s proposed approach," the report summarizes. "Foreseeable risks included post‑conflict political disintegration and extremist violence in Iraq, the inadequacy of US plans, [and] the UK’s inability to exert significant influence on US planning."

The United States, too, knew of the war’s risks. According to Chilcot’s findings, "the State Department judged that rebuilding Iraq would require ‘a US commitment of enormous scope’ over several years."

Yet the United States failed to plan for postwar sectarian infighting and had no serious plan for rebuilding Iraqi institutions after the invasion.

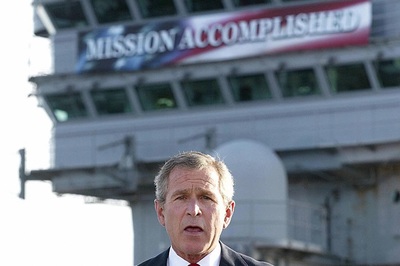

This, Chilcot judges, owed principally to Donald Rumsfeld’s Department of Defense. "Many in the DoD anticipated US forces being greeted as liberators who would be able leave Iraq within months, with no need for the US to administer the functions of Iraq’s government after major combat operations," Chilcot concludes.

Perhaps the most damning testimony in the report on this point comes from Sir David Manning, a foreign policy advisor to Tony Blair in the runup to the war. Here’s what Manning told Chilcot:

"It’s quite clear throughout 2002, and indeed throughout 2003, that it is the Pentagon, it’s the military, who are running this thing...Bush had this vision of a new Middle East. You know, we are going to change Iraq, we are going to change Palestine, and it’s all going to be a new Middle East.

But there were…big flaws in this argument. One is they won’t do nation-building. They think this is a principle. So if you go into Iraq, how are you going to achieve this new Iraq? And the military certainly don’t think it’s their job."

In short? The United States had ample warning that reconstructing Iraq would be a difficult and dangerous task, as did its key ally. Yet the key war planners assumed the war would be a cakewalk. Iraqis and coalition soldiers paid the price.

"Bush’s poodle"

The more you read the report, the more this sort of American ignorance and bullheadedness seems like a pattern, not an aberration. Time after time, the United States charged ahead with terrible ideas, often dragging the UK along for the ride.

This story starts in 2001. According to Chilcot, the US government became dead set on invading Iraq shortly after the 9/11 attacks — despite no meaningful links between al-Qaeda and Iraq.

"It was the US Administration which decided in late 2001 to make dealing with the problem of Saddam Hussein’s regime the second priority, after the ousting of the Taliban in Afghanistan, in the ‘Global War on Terror,’" Chilcot finds. "In that period, the US Administration turned against a strategy of continued containment of Iraq, which it was pursuing before the 9/11 attacks."

The UK, interestingly, did not initially agree. "Its stated view at that time was that containment had been broadly effective, and that it could be adapted in order to remain sustainable. Containment continued to be the declared policy of the UK throughout the first half of 2002," it explains.

Blair, personally, was somewhat skeptical of the case for war. "I still don’t see how the military option will work, but I guess there will be an answer," he said in February 2002.

Yet two months later, Blair essentially committed the UK to supporting a US invasion of Iraq during a private meeting with President Bush at the latter’s ranch in Crawford, Texas. Not only did Blair give in, Chilcot explains, but he gave up on the UK’s preferred policy of waiting to see if United Nations and International Atomic Energy Agency inspectors could do their job. The UN skeptics at the US ended up setting the terms of the war.

"Most crucially, the US Administration committed itself to a timetable for military action which did not align with, and eventually overrode, the timetable and processes for inspections in Iraq which had been set by the UN Security Council," Chilcot finds.

"The UK wanted [the UN] and the IAEA to have time to complete their work, and wanted the support of the Security Council, and of the international community more widely, before any further steps were taken. This option was foreclosed by the US decision."

This, according to Chilcot, was part of a broader pattern of UK deference to the US. "On these and other important points, including the planning for the post-conflict period and the functioning of the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), the UK Government decided that it was right or necessary to defer to its close ally and senior partner, the US," Chilcot concludes.

That includes on decisions that would prove to be disastrous. Disbanding the Iraqi army after the invasion, for example, immediately rendered a huge number of military-trained young men unemployed, many of whom ended up joining extremist and insurgent groups. It was a critical cause of the postwar disaster — yet L. Paul Bremer, head of the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), basically told the UK that this would be how things were after the decision was made.

The UK, according to Chilcot, "played little or no formal part" in the decision to disband Iraq’s army.

Blair prioritized the special relationship

Why did the UK defer to the American view, on both the war and its execution? The basic conclusion of Chilcot is very clear: The UK leadership thought that standing up to America would threaten their partnership. This probably wasn’t true — the US and France get along fine nowadays. But the UK leadership thought it was, and that made all the difference.

A crucial passage from Tony Blair’s memoirs, highlighted by the report, sheds light on this mindset:

I agreed with the basic US analysis of Saddam as a threat; I thought he was a monster; and to break the US partnership in such circumstances, when America’s key allies were all rallying round, would in my view, then (and now) have done major long-term damage to that relationship.

As the more powerful partner, by far, in the "special relationship," the US got to set the terms of how things worked. Blair, an interventionist by inclination anyway, was mostly content to go along — despite the warnings in the UK government that the war would be a mess. The popular nickname for Blair after the invasion, "Bush’s poodle," was more than a little earned.

"Mr Blair and President Bush continued to discuss Iraq on a regular basis. It continued to be the case that relatively small issues were raised to this level," the Chilcot report writes, a statement made all more the damning by its reserved tone. "The UK took false comfort that it was involved in US decision‑making from the strength of that relationship."

This, I think, is the ultimate lesson of Chilcot for America. The United States faces many constraints in global politics, but it is ultimately still the world’s only superpower and the driving force behind the trans-Atlantic alliance. When the US makes a bad decision, even a historically terrible one, it has the capability to drag at least some of its chief allies with it.

This responsibility cannot be evaded by pointing to the mistakes of those allies, legion as they may be. The Iraq War was principally an American project, conceived of and designed in Washington. The invasion’s failures were predictable and predicted, yet the Bush administration chose to launch it anyway.

This was a decision America made. This latest report merely underscores just how terrible a decision it truly was.

Source www.vox.com/2016/7/6/12105616/chilcot-report-iraq-blair-bush

RSS Feed

RSS Feed