Iraq’s currency has been struggling for months against the dollar since new restrictions were imposed by the US Federal Reserve on how the country's central bank trades the dollars it receives from oil sales.

The subsequent liquidity crisis has meant the government is failing to pay the salaries of millions of public servants, as well as pensions and payments to other beneficiaries of social welfare programmes.

Iraq has been one of the largest importers of Iranian goods over the last two decades, in particular gas, electricity, food, and construction materials.

Official trade exchange between the countries amounts to approximately $14bn.

Because of US sanctions imposed on Iran in 2018, Iraq has struggled to pay Iran for its purchases from 2019-2021.

At times, Iran has cut electricity and gas supplies in midsummer - when temperatures rise to 50 degrees Celsius - to pressure Iraq into paying these debts.

Sources suggest most or all of that debt has been settled, with the last payment going through in October 2022.

But rather than the dollars Iran received pre-sanctions, Baghdad has used Iraqi dinars instead, officials told MEE.

The new payment system was worked out to avoid the anti-government protests that would have inevitably followed a cut in energy supplies in Iraq, they said.

Yet Iran was nonetheless able to turn these dinars into dollars - which are far more useful - using a currency auction the Central Bank of Iraq holds daily to convert the dollars it received from oil sales.

But since November, the US Federal Reserve, which holds the money Iraq makes from oil sales and delivers it to Baghdad by request, has imposed restrictions aimed at stopping Iran from accessing these dollars and combatting money laundering.

As MEE previously revealed, this led to parties including sanctioned states and criminals to find new ways to obtain dollars, such as the black market and dollar smuggling through Kurdistan.

And with Iran and others now avoiding changing dinars through the auction, Iraq has been unable to trade its dollars for the local currency it requires to meet its needs.

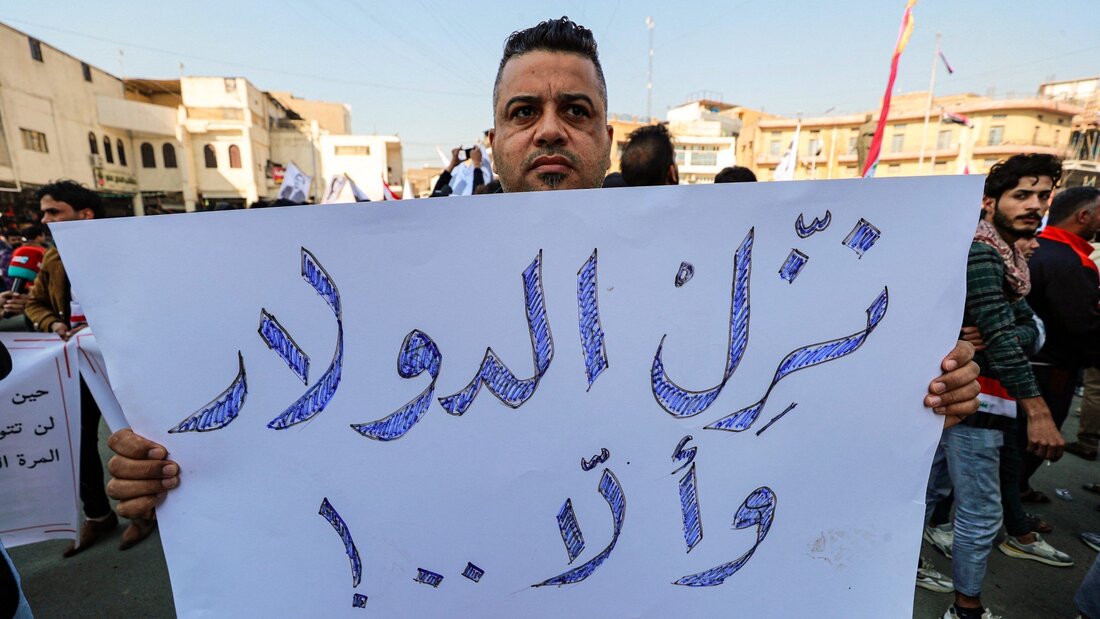

All this continues to place pressure on the dinar.

In January, its black market price rose to 1,700 to the dollar from 1,480 in October.

Traders have described the fluctuations as “terrifying”, saying there is huge competition for dollars with speculators willing to pay “any price”. Meanwhile, the prices of consumer goods continue to rise.

The Iraqi government has introduced various measures to control the exchange rate, including reducing the official rate to 1,300 dinars. Though the black market rate has dropped to around 1,500 dinars, it remains highly volatile.

The impact of handing Iran large amounts of dinars - that it is now unable to trade for dollars - is still being felt.

"Paying Iranian debt in Iraqi dinars was not a calculated step. The financial crisis we are currently suffering from is caused by this stupid step," a senior Iraqi official told MEE.

"Iran obtained huge amounts of the Iraqi currency and it desperately needs the US dollar, so what did the decision-makers think that Iran would do with this currency? Were they thinking that Iran would distribute them as gifts to the Iraqis, or they would invest them in the Iraqi market?" he asked.

"Their thinking was limited to achieving quick, imaginary successes to prove that they are the most capable of dealing with Iraq's intractable problems, so they took us out of a well to throw us into a sea.”

Intractable problems and patchwork solutions

Despite having one of the largest oil reserves in the world, Iraq has suffered from severe energy shortages since the 1990s, due to conflicts, sanctions, mismanagement, and a failure to develop infrastructure.

In recent summers, the lack of power, drinking water, and other essential services has prompted mass demonstrations, especially in the south.

To patch over the supply issues, Iraq has had to import energy and gas - much of it from Iran next door.

Officially, Iraq spends around $900m a month on Iranian goods, according to Iranian officials. Fifty percent of that is electricity and gas.

Aware of Iraq’s precarious situation, Washington has exempted Iraq from its sanctions on Iran, but problems paying for the purchases arose from day one.

The United States only agreed to waive sanctions if Iraq placed the funds in the Trade Bank of Iraq with the understanding that it would be used later by Iran to pay for food and medicine.

"However, this was not enough for Iran, as the account's movement is subject to American control," an Iraqi official said.

Iran instead demanded another way to receive its money and used threats to the energy supply as a way to pressure Baghdad into giving it what it wants.

In October 2019, the energy shortages became an existential crisis for Iraqi authorities, when huge demonstrations rocked various central and southern provinces, as well as Baghdad.

Adel Abdul-Mahdi’s government and some Iran-backed armed factions waged a bloody crackdown on the protests, which had significant backing from the supporters of Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr.

The ensuing bloodbath forced the collapse of Abdul-Mahdi’s administration and early elections.

The next prime minister, ex-intelligence chief Mustafa al-Kadhimi, and his backer, Sadr, sought to find quick solutions to the intractable problems that Iraq suffers from, including the Iranian debt, officials told MEE.

Later, in April 2022, when Iraq was swept up in a political vacuum following the inconclusive elections the previous October, the Sadrists suggested an emergency law to act as a mini-budget.

The debt to Iran that had been accumulated since 2019 was one of the most pressing issues for Kadhimi’s government at the time.

“Sadr had to find a way out for his ally," one of Kadhimi’s former advisors told MEE.

At the same time, Sadr wanted to present "a gesture of goodwill to the Iranians to prove that his project does not target them or threaten their interests," the adviser said.

The law allocated four trillion Iraqi dinars (about $3bn) "to pay off the electricity ministry’s foreign debt and the debts for the purchase of gas and energy".

That June, parliament approved the law and the Iraqi government started to pay what it owed directly to Iranians in dinars. The last payment was in October, officials said.

In February 2019, the Central Bank of Iraq concluded an agreement with the Central Bank of Iran, allowing customers of both banks to open accounts in the two countries and conduct their banking transactions in dinars and euros.

The Iraqi Central bank said at the time this was done “to remove obstacles to paying Iraq’s debts related to gas and electricity exports”.

An Iraqi politician close to Tehran told MEE he believed Washington predicted the strain on Iraq’s currency when it allowed Baghdad to pay Iran in dinars.

“If they didn't, then they missed a lot," he said.

“The Iranians are very smart and they are investing in all the details that serve their goals. They were clear from the beginning. They said if you could not pay in dollars, pay in dinars and leave it to us,” he added.

“It is not their problem if their rival is arrogant and treats others as helpless, and they will follow their own paths."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed