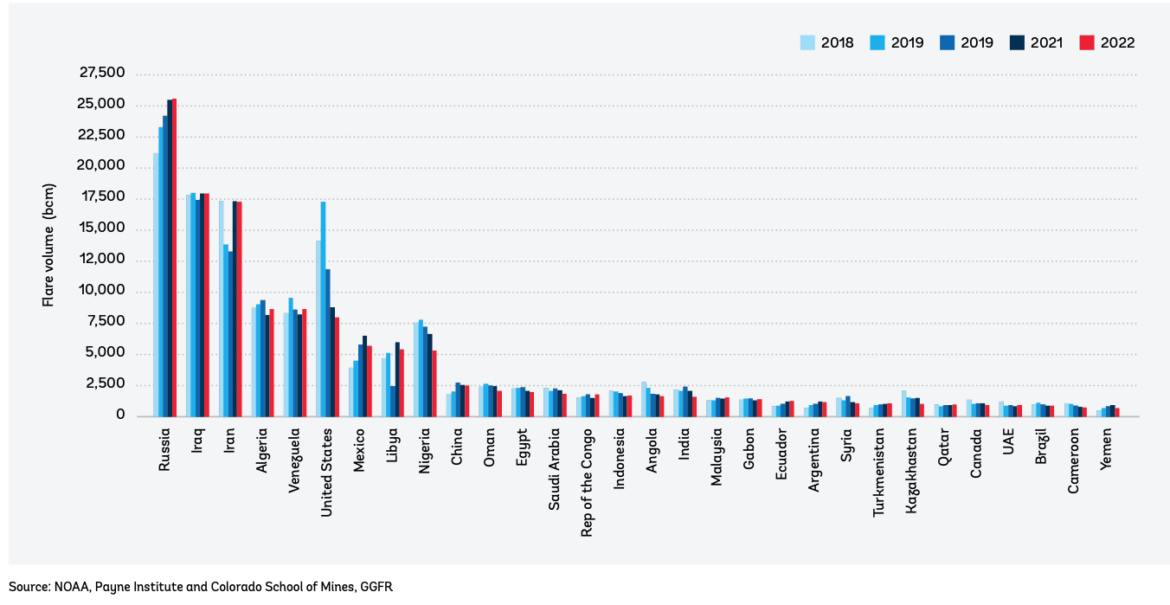

Despite pledges by all the top oil companies and many countries to end routine flaring by 2030, in countries like Iraq, the flares are still burning. In 2022, the country was the second-largest source of gas flaring worldwide, even as figures show that the country is warming twice as fast as the global average.

In a recent investigation, a team at BBC News Arabic headed to southern Iraq to explore the impact of gas flaring on the environment and public health.

The resulting film, “Under Poisoned Skies,” details the efforts of Shukri al-Hassen, a professor at the University of Basra, to measure pollution levels near oil fields. The makers of the documentary claim some of the world’s biggest oil companies have managed to avoid declaring a substantial amount of flaring emissions, “giving the impression to investors and the public that they are on track to hit” their pledged 2030 targets.

The tests conducted by the Iraqi professor represent the first instances of gathering public data on pollution levels in these communities. The results were concerning and prompted him to ask: “Why are we paying the price for this smoke that comes from the oil companies?”

In March, the documentary won the Royal Television Society’s Current Affairs – International Award, and was described by judges as “an enterprising and original piece of journalism.” The following interview is with the film’s director Jessica Kelly, and producer, Owen Pinnell, and has been lightly edited.

Jessica Kelly: At the time there seemed to be a real lack of climate reporting on the Middle East, especially around the oil and gas industry. On Twitter, we saw horrifying images being shared by people in southern Iraq of huge apocalyptic flames and clouds of black smoke from oil fields right next to where people live. It felt like a very visual starting point through which to tell a climate story and so we started to investigate.

Owen Pinnell: We found out that this was all caused by something called gas flaring — a process where waste gas from oil drilling is burned in the open air. This is both extremely damaging for the global climate, because it releases greenhouse gases, but also damaging to people’s health.

We started speaking to people from these communities in Iraq and they told us the same story again and again — so many people here are sick with cancer, specifically leukemia. So we decided to investigate whether these two things could be connected.

Pinnell: We used multiple open source methods in the early stages — we looked at satellite imagery to determine how close the flares were to residential areas, and analyzed industry data to calculate how big the emissions were from these fields.

We soon found out that there was no reliable data on air pollution levels in Iraq, and very little data on cancer rates. We instead drew on scientific studies carried out in the US and elsewhere that linked high levels of gas flaring to cancer. This informed our decision to carry out a “pilot study,” measuring the levels of carcinogenic pollutants — including benzene and naphthalene — in the air and in the urine of children living near the oil fields.

GIJN: Were there any challenges or obstacles you faced while conducting this investigation? If so, what were they, and how did you overcome them?

Kelly: We are not able to go into too much detail for the safety of our team in Iraq, but the presence of militia and Iraqi intelligence was felt throughout our work. One of our team was threatened by intelligence [officers] and had to leave the project. We also had an interview shut down just for asking about flaring. Because more than 90% of Iraq’s economy comes from oil it’s extremely difficult to criticize the industry.

We spent weeks looking for a scientist who would be brave enough to take part in the study. And it was nearly impossible to film with environmental activists from Basra due to the risk to their lives. One of the biggest obstacles was how to film in Rumaila — the field near where Ali lived that is run by BP — as it is cut off by security checkpoints and our applications to film there were rejected. That’s when we decided to give Ali a camera so that he could document his life himself.

It’s also worth mentioning the extreme weather conditions in Basra. We were there in August at one point when temperatures sometimes exceeded 50°C (122°F). In other months there were sand storms which meant we lost whole days of filming. The pollution is also unavoidable, there’s an acrid smell in the air and the sky is yellow-tinged, we were lucky that we could go home and breathe comparatively clean air outside Iraq. But for Iraqis living in Basra there’s no escape.

GIJN: How did you ensure the safety of yourselves and the people you interviewed during the investigation?

Pinnell: We worked with the BBC’s high risk team throughout our filming, who helped to ensure our safety and the safety of our contributors. We also kept in regular contact with our contributors after the documentary aired, so that we could respond to any security issues that arose in response to the film. Basra can be dangerous at night so we had to use armored vehicles in order to film the flares after dark.

As you can see from the film, many of the contributors are anonymous. Some of the journalists and freelancers we worked with in Iraq also stayed anonymous, to avoid any potential repercussions. We are so grateful to Iraqi contributors and colleagues alike for the personal risks they took to work on the story.

GIJN: Can you describe the role of environmental scientists in this investigation and how they contributed to the findings?

Kelly: This investigation wouldn’t have been possible without Professor Shukri al-Hassen, the Iraqi environmental scientist who played a leading role. We worked closely with him to devise the plan for pollution monitoring. His easy manner and rapport with people living in the gas-flaring towns, and professionalism in carrying out the sampling, freed us up to focus on filming. He was also incredibly passionate about the subject, having grown up in Basra his whole life, witnessing the destruction of the environment and the impact of pollution on people’s health. He took a big risk by criticizing the oil industry and so his bravery cannot be overstated.

Pinnell: We also spoke to scientific experts from around the world — including from Columbia University, Imperial College London, and Greenpeace Science Unit — who advised us on methods we could use to carry out a pilot study. Once we had the results, we needed the advice of this panel of experts to analyze and interpret the data. A special mention should go to Aidan Farrow, who works at the Greenpeace Science Unit at Exeter University, who helped us identify the right pollution monitors and trained us in how to use them.

Kelly: We had at least one interview shut down… There was a high level of risk in bringing pollution monitors into the country and filming in Rumaila, which is heavily guarded and for which we were denied permits to film, despite requesting permission on several occasions. Even Iraqi ministers and local politicians who requested access to the area were ignored.

GIJN: Were any mistakes or oversights made during the investigation, and how were they addressed?

Kelly: Originally we were only going to measure the air for benzene, but halfway through the investigation we realized we needed another type of monitoring to show how much of that benzene was actually getting inside people’s bodies, that’s when we decided to extend the investigation and also measure the pollution levels in children’s urine. This technique was shared with us by Martin Boudot from Premiere Lignes, who recently put out a documentary about gas flaring in Iraq and France: “Les damnés du pétrole,” [Damned by Oil].

Pinnell: We would have loved to have gone into more detail on the practice of “venting,” which is when gas isn’t flared but instead allowed to spew out into the atmosphere unburned, in the form of methane. This is even more damaging than flaring, but is harder to explain and measure, as it disperses quickly. It is also invisible. We did include some information on methane venting in longer reads that went out around the film, and in the film the professor explains how there is also methane emitted during gas flaring.

GIJN: What was the most surprising or shocking finding from the investigation?

Pinnell: On the climate side, I think finding out that BP’s flaring emissions from just one field — Rumaila — were greater than the total flaring emissions the company admitted to globally, was shocking. This finding, explained in the documentary by Greenpeace Unearthed’s Joe Sandler Clarke, opened up a whole new avenue of inquiry for us, as we realized this was effectively an “accounting trick” that most major oil companies were using to make it look like they were living up to their promises on climate. It blew a huge hole in their claims and has led to considerable criticism amongst ethical investors – for example the UK’s biggest pension fund, NEST, led a rebellion at BP’s annual shareholder meeting citing our film as an influence.

[BP co-manages the field at Rumaila but is not the operator. It refused numerous interview requests from the BBC documentary team and in response to the investigation, said it was working with its partners to look at the issues raised. “This includes a review of processes and procedures to support the community and understand any concerns — this is ongoing.” It also told the BBC it was “standard practice” to report flaring emissions from activities only where it is the operator. Rumaila’s flaring and operational data, it said, “are therefore not included in our reporting.”]

Kelly: Witnessing the human cost was also shocking. Over the course of the investigation, we filmed four children with cancers that have strong links to fossil fuel pollution, who lived near the oil fields and all of them have now passed away. We saw firsthand the huge disparity between the type of cancer treatment available in Iraq and what most people take for granted in say, the UK.

GIJN: What impact do you hope this investigation will have regarding policy change and public awareness?

Pinnell: Personally, I hope that more attention is paid to the health problems that are caused by practices that are destructive to the climate, like gas flaring. And ultimately that companies and governments stop treating areas like Rumaila as a “sacrifice zone” — where profit and resource extraction are put above people’s fundamental human right to a healthy environment.

Kelly: I hope that the film makes governments and the oil companies acknowledge the full extent of the damage caused by gas flaring. At the end of the day, it is an entirely avoidable practice, the gas should be captured and used as fuel, not just burned off.

Even in his final days, he was looking forward to the opportunity of challenging BP’s chief executive on the company’s pollution at its Annual General Meeting. Instead, his grieving father stepped in and challenged BP in a rare moment of accountability for a usually untouchable global behemoth — the company refused numerous interview requests from us, preferring to issue formal letters.

The lesson we’re taking from this is that it’s really important to stay in touch with the people in our investigations after publication. And to give them the chance to speak their truth to power long after the initial film has been released.

Kelly: It’s so important to make sure you have the time and the resources to invest in the impact of the film after it’s gone out. We’re lucky that they take this really seriously at BBC News Arabic. We were able to take the film to COP27 in Egypt, we even bought Ali with us, and that enabled us to show the film to really influential environmental campaigners and industry insiders.

GIJN: Are there any plans for future investigations or follow-up reports related to this topic?

Pinnell: We are planning to follow up with an investigation that looks at other “sacrifice zones” around the world, where health and livelihoods are being harmed by the oil and gas industry. We also learned in a screening at Columbia University that the idea of doing pollution monitoring as part of journalistic investigation is being taken on in New York, measuring the impact of pollution from traffic on community health. We were able to connect Professor Shukri’s students in Iraq with students at Columbia for future collaborations.

Kelly: Many promises were made in the wake of our investigation by the oil companies and the Iraqi government to clean up, so we are continuing to keep a close eye on them. We want to make sure the stories of the children and young people we met like Ali are not forgotten. And that the sacrifices he made to tell the world about his community’s situation right up to the week of his tragic death are not in vain.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed