But an unreleased analysis presented at recent coalition meetings by the United Nations speaks to a much more complicated and fluid situation on the ground — one characterized by delicate humanitarian considerations and the real possibility of an Islamic State resurgence.

According to the U.N., five of the areas newly liberated from the group urgently require stabilization. “There is a risk that if we don’t stabilize these areas quickly, violent extremism might emerge again. The military gains that have been made against [the Islamic State] could be lost,” Lise Grande, head of the United Nations Development Programme in Iraq, told Foreign Policy.

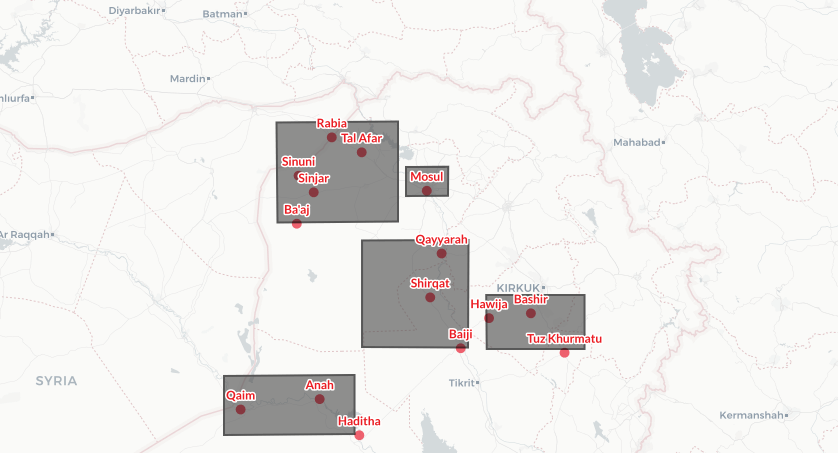

The areas, centered around the group’s former strongholds in northern Iraq, demonstrate the wide array of issues facing the Iraqi government and its international allies as they attempt to channel stabilization funds to sensitive areas and clamp down on a rapidly evolving threat.

According to both U.N. and U.S. officials who worked on crafting the document, the designated areas at risk were based on a number of metrics including tallies of security incidents, known Islamic State sleeper cells, the presence of political groups supportive of the group, and religious figures known to echo the group’s messages. “These are the areas that need specific attention,” said the American official, who requested anonymity to discuss sensitive negotiations.

Two of the areas, one centered on the city of Tal Afar and the other on Qaim, were also included for their proximity to the Syrian border. “There are still pockets of ISIS in Syria,” said the State Department official. “Adjacent to those pockets are areas that have been most recently liberated, and they are areas that have traditionally been politically volatile.”

The other areas highlighted on the map, including clusters near the towns of Hawija, Tuz Khurmatu, and Shirqat, were selected because of long-standing political and security concerns. “These have always been critical — even before ISIS. Hawija and Tuz Khurmatu [a disputed city near Kirkuk] have always been political flashpoints,” said the U.S. official.

These towns and cities, moreover, are all in a band of ethnically diverse communities, where Sunnis, Shiites, and Kurds live in close proximity. Unlike the ethnically homogenous Kurdish region or Shiite-dominated southern Iraq, these areas have frequently seen bouts of sustained instability.

In the past, the shifting ethno-sectarian balance in these areas led to fears, especially among Sunni communities, of displacement and discrimination. This persistent sense of disenfranchisement, combined with distrust of the central government and other complex factors, contributed to the initial rise of the Islamic State.

The underlying instability in those regions is part of what prompted the U.N. to compile the map, as a way of guiding stabilization funding — money used to facilitate the return of displaced Iraqis — to the most sensitive and potentially explosive areas. “What they’re saying is that, unless we continue to work to stabilize these areas immediately, we run the risk of backsliding,” said the U.S. official. “It’s where the greatest needs are.”

Some analysts, however, worried that the document left out key areas of potential concern. “They’re a couple places that just aren’t on the map,” said Michael Knights, a senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

“For instance, the most serious red dot that you could possibly put on this map, but it isn’t there, would be Diyala province,” he said.

Diyala has long been a hotspot for violence. According to some counts, the number of bombings and direct attacks against both civilians and military targets in 2017 was as high as in parts of 2013, during the Islamic State’s early days. “What observers are seeing in Diyala is a full-fledged Islamic State-led insurgency,” noted an August 2017 paper published by West Point.

Coalition officials noted that the map’s designations were based partially on political concerns, but also on other factors, including the number of civilian returnees. “Diyala has been liberated for a while,” the State Department official told FP. “It’s always a hotspot, but a lot of money and effort has already gone into it, and almost all the population has returned.”

Knights also pointed to the Baghdad “belts” — residential and agricultural areas ringing the city — as another potential flashpoint. In the past, higher levels of insurgent violence were preceded by what Knights termed “microbombings,” low-profile attacks that often flew under the radar of the central government or U.S. counterterrorism officials.

“Individually, they aren’t high-profile events: they were all markets, bus stops, etc.,” he said. “But when you add them up, there are a lot of them. It’s really inflammatory stuff.”

The risk, explained Knights, is potential complacency. “The perception right now is that they’re quiet,” he said, “and that’s not really a good guideline.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed