The number killed in the 9-month battle to liberate the city from the Islamic State marauders has not been acknowledged by the U.S.-led coalition, the Iraqi government or the self-styled caliphate.

But Mosul’s gravediggers, its morgue workers and the volunteers who retrieve bodies from the city’s rubble are keeping count.

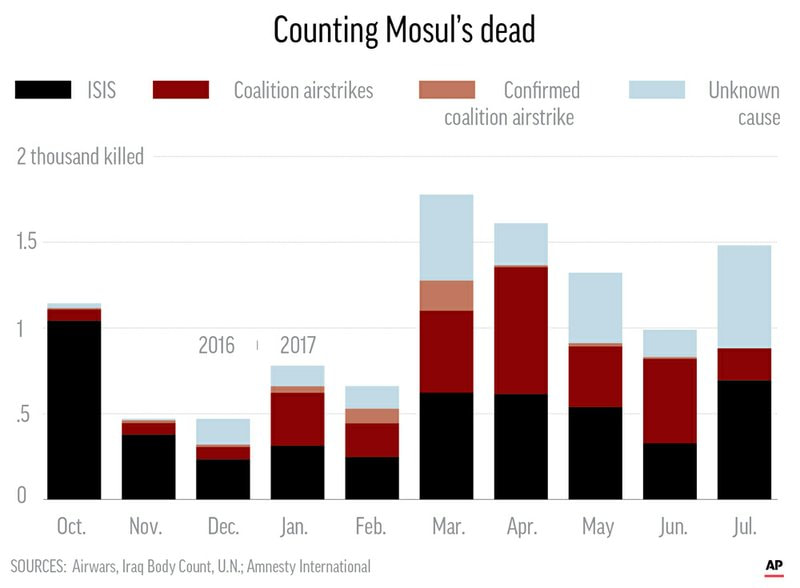

Iraqi or coalition forces are responsible for at least 3,200 civilian deaths from airstrikes, artillery fire or mortar rounds between October 2016 and the fall of the Islamic State group in July 2017, according to an Associated Press investigation that cross-referenced independent databases from non-governmental organizations.

The coalition, which says it lacks the resources to send investigators into Mosul, acknowledges responsibility for only 326 of the deaths.

“It was the biggest assault on a city in a couple of generations, all told. And thousands died,” said Chris Woods, head of Airwars , an independent organization that documents air and artillery strikes in Iraq and Syria and shared its database with the AP.

In addition to the Airwars database, the AP analyzed information from Amnesty International , Iraq Body Count and a United Nations report. AP also obtained a list of 9,606 names of people killed during the operation from Mosul’s morgue. Hundreds of dead civilians are believed to still be buried in the rubble.

Of the nearly 10,000 deaths the AP found, around a third of the casualties died in bombardments by the U.S.-led coalition or Iraqi forces, the AP analysis found. Another third of the dead were killed in the Islamic State group’s final frenzy of violence. And it could not be determined which side was responsible for the deaths of the remainder, who were cowering in neighborhoods battered by airstrikes, IS explosives and mortar rounds from all sides.

But the morgue total would be many times higher than official tolls. Iraqi Prime Minister Haidar al-Abadi told the AP that 1,260 civilians were killed in the fighting. The U.S.-led coalition has not offered an overall figure. The coalition relies on drone footage, video from cameras mounted on weapons systems and pilot observations. Its investigators have neither visited the morgue or requested its data.

What is clear from the tallies is that as coalition and Iraqi government forces increased their pace, civilians were dying in ever higher numbers at the hands of their liberators: from 20 the week the operation began in mid-October 2016 to 303 in a single week at the end of June 2017, according to the AP tally.

After the city fell to IS in 2014, undertakers like him handled the victims of beheadings and stonings; there were men accused of homosexuality who had been flung from rooftops. But once the operation to free the city started, the scope of Mohammed’s work changed yet again.

“Now I carve stones for entire families,” Mohammed said, gesturing to a stack of four headstones, all bearing the same name. “It’s a single family, all killed in an airstrike,” he said.

DYING AT HOME, ON THE FRONT

Mosul was home to more than a million civilians before the fight to retake it from IS. Fearing a massive humanitarian crisis, the Iraqi government dropped leaflets or had soldiers tell families to stay put as the final battle loomed in late 2016.

Thousands were trapped as the front line enveloped densely populated neighborhoods.

Blast injuries, gunshot wounds and shrapnel wounds killed thousands as the Mosul operation ground westward, according to morgue documents.

At the same time, Islamic State fighters took thousands of civilians with them in their retreat west. They packed hundreds of families into schools and government buildings, sometimes shunting civilians through tunnels from one fighting position to another.

They expected the tactic would dissuade airstrikes and artillery. They were wrong.

As the fight punched into western Mosul, the morgue logs filled with civilians increasingly killed by being “blown to pieces.”

By early March, Iraqi officials and the U.S.-led coalition could see that civilian deaths were spiking, but held the course. The result, in Mosul and later in the group’s Syrian stronghold of Raqqa, was a city left in ruins by the battle to save it.

Most of the civilians killed in west Mosul died under the weight of collapsed buildings, hit by airstrikes, mortars, artillery shells or IS-laid explosives. The morgue provided lists of names of civilians and place of death. Names often included entire families.

The coalition has defended its operational choices, saying it was Islamic State that put civilians in danger as it clung to power.

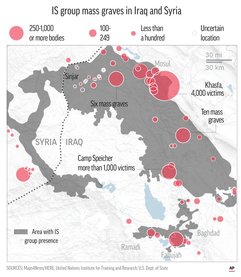

An AP investigation has found at least 133 mass graves left behind by the Islamic State group. Estimates total between 11,000 and 13,000 bodies in the graves.

An AP investigation has found at least 133 mass graves left behind by the Islamic State group. Estimates total between 11,000 and 13,000 bodies in the graves. “Without the Coalition’s air and ground campaign against ISIS, there would have inevitably been additional years, if not decades of suffering and needless death and mutilation in Syria and Iraq at the hands of terrorists who lack any ethical or moral standards,” he added.

Civilian deaths in the second half of the battle reflected the looser rules of engagement for airstrikes and the sheer numbers of trapped residents. From Oct. 17 to Feb. 19, the AP tally found at least 576 deaths by coalition or Iraqi munitions.

From Feb. 19 — when the fight crossed the Tigris River — to mid-July, there were nearly 2,400 civilian deaths. That total is in addition to the 326 confirmed by the coalition in the city. The U.S. and Australia are the only two coalition countries to acknowledge civilian deaths, although France had fighter jets and artillery and the UK also carried out airstrikes.

Of the nearly 10,000 names listed by the morgue, around 4,200 were confirmed as civilian dead in the battle. The AP discarded names that were obviously those of Islamic State fighters, and casualties brought in from outside Mosul. Among the remaining 6,000 are likely some number of Islamic State extremists, but the morgue civilian toll tracks closely with numbers gathered during the battle itself by Airwars and others.

Neither toll includes thousands of people killed by Islamic State who are believed to be in mass graves in and around Mosul, including as many as 4,000 in the natural crevasse known as Khasfa.

Imad Ibrahim, a civil defense rescuer from west Mosul, survived the battle to retake the city and is now tasked with excavating the dead. He mostly works in the Old City, where on a recent day the streets still reeked of rotting flesh.

“Sometimes you can see the bodies, they’re visible under the rubble, other times we dig for hours and suddenly find 15 to 30 all in one place. That’s when you know they were sheltering, hiding from the airstrikes,” Ibrahim said.

Behind him an excavator dug through jagged cement blocks, searching for the body of a woman who was hiding in her home when it was hit by an airstrike.

Ibrahim said he spent years waiting for liberation, but that the victory itself was hollow.

“Honestly, none of this was worth it.”

By dawn, dozens of Mosul families begin to line up outside the civil defense office each day. One by one they flatly describe their personal tragedies: “we buried my cousin’s body in the garden under the tree.” ″My mother was hiding in the back of the house, near the kitchen when the airstrike hit her home.” ″We buried my father in the street in front of our home after he was shot.”

Radwan Majid said he lost both his children to an airstrike in May.

“We can see their bodies under the rubble, but we can’t reach them by ourselves,” he said. “All I want is to give them a proper burial.”

Reports of civilian deaths began to dominate military planning meetings in Baghdad in February and early March, according to a senior Western diplomat who was present but not authorized to speak on the record.

After allegations surfaced that a single coalition strike killed hundreds of civilians in Mosul’s al-Jadidah neighborhood on March 17, the entire fight was put on hold for three weeks. Under intense international pressure , the coalition sent a team into the city to investigate.

A Whatsapp group shared by coalition advisers and Iraqi forces coordinating airstrikes previously named “killing daesh 24/7” was wryly renamed “scaring daesh 24/7.”

“It was clear that the whole strategy in western Mosul had to be reconfigured,” said the Western diplomat.

But on the ground, Iraqi special forces officers said after the operational pause, they returned to the fight just as before.

The Whatsapp group’s name was changed back to “killing daesh.”

The 500-pound bomb, the investigation concluded, “appropriately balanced the military necessity of neutralizing (two IS) snipers.” Witnesses and survivors told AP that IS had not set any explosives in the house that was hit, which was packed with families sheltering from the fighting.

At the time, just two American officers were fielding all allegations of civilian casualties in Iraq and Syria from a base in Kuwait. The team now has seven members, though none sets foot inside the city or routinely collects physical evidence.

The Americans say they do not have the resources to send a team into Mosul; an AP reporter visited the morgue six times in six weeks and spoke to morgue officials and staffers dozens of times in person and over the phone.

Because of what the coalition considers insufficient information, the majority of civilian casualty allegations are deemed “not credible” before an investigation ever begins.

Col. Joseph Scrocca, a coalition spokesman, defended the coalition figures in an interview in May, saying they may seem low because of a meticulous process designed to “get to the truth” and help protect civilians in the future.

“I do believe the victims of these strikes deserve to know what happened to their families. We owe them that,” Scrocca said.

Daoud Salem Mahmoud survived the fight for the Old City by hiding with his family in a windowless room deep inside their home.

With the fight over, Mahmoud now returns to his neighborhood daily to retrieve the dead. He’s recovered hundreds of bodies of extended family members and neighbors.

A large, imposing figure, Mahmoud breaks down in tears when asked to describe specific days or events at the height of the violence. But without a moment of hesitation he said he believes the fight to retake the city was worthwhile.

“Everything can be rebuilt, it’s the lives lost that cannot be replaced,” he said, then shaking his head, added, “this war, it turned Mosul into a graveyard.”

Source: apnews.com/bbea7094fb954838a2fdc11278d65460

RSS Feed

RSS Feed